(director: with strings, in eighths, lyric, of David)

* * *

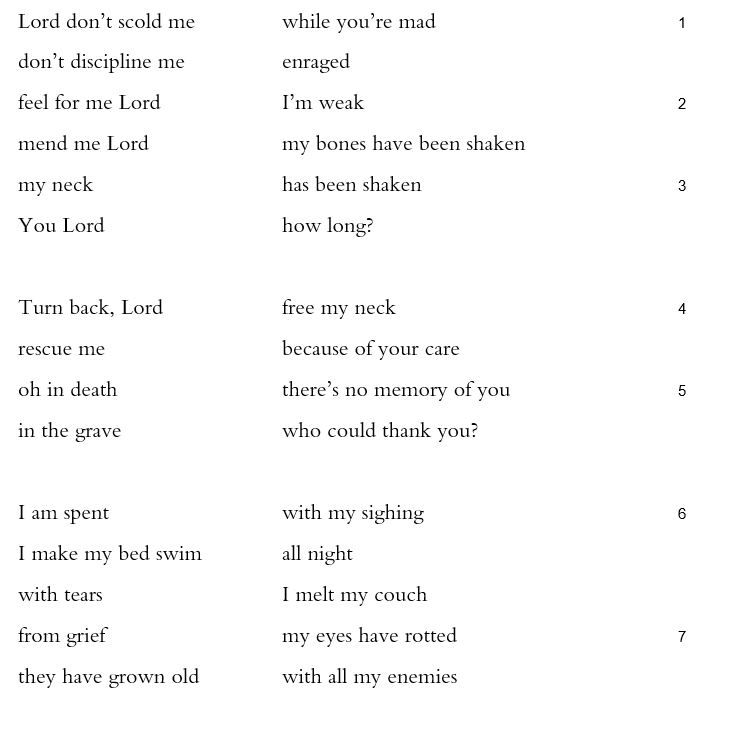

The sharp-eyed critic Bernhard Duhm, who allegedly quipped that “commentaries make one stupid,” wrote of Psalm 6 in his 1899 commentary on the Psalms, “as a reading at a Christian sickbed this psalm is not suitable.” Two thoughts arise. First, the modifier “Christian” seems wholly unnecessary. Second, it stuns that this advice should need to be said. What dim chaplains have seen fit to console loved ones with a text that blames enemies for illness and flatters God to relent from punishment: “in death | there’s no memory of you / in the grave | who could thank you?” (6:5)? But perhaps Cassiodorus’ traditional grouping of seven penitential psalms (Pss 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, 143) led passive priests and pastors to flip to this one too quickly at bedsides.

In translation and in the original, it’s evident how many times “me” shows up, and how thickly the tears flow. Some psalms are just weaker than others, as Duhm had the courage to admit: “[those] who know only the best poems… and mostly have a false conception of their originality usually consider the Psalter the classic model of sublime oriental poetry; however, the one who reads the collection in their original… perceives the dominance of the conventional and the extensive dependency of most poems upon older models” (xxvii, qtd. in Kurtz, “The Spirit of Jewish Poetry” 2020).

Not that the psalm is poorly structured. It turns on the trope of turning, which is one of the most significant images in both poetry and the Bible. Interestingly, the word “verse” refers to the turning of a line (see “reverse,” “inverse,” and “version”), and the volta of a sonnet is the turn from octave to sestet. Biblically, the Lord turns towards or away, the people turn towards or away, they swerve, their hearts or faces are turned, they return. “Turn back, Lord,” the speaker pleads in verse 4, and then demands that enemies “turn from me” in verse 8, which the final verse actualizes: “they turn and blanch” (6:10). In a deft move, their blanching—their shame—is their turning: yashubu yeboshu, in which bosh literally turns shuv around.

So Psalm 6 is not without its moments. It closes well, returning to the image of being shaken (6:2,3,10) and to the image of the eye from verses 6 and 7 which now “blink” (10). Verse 5 is nice, pairing that statement about death and memory with a rhetorical question about the grave and gratitude.

It’s just marred by its sentiment, its self-pity, and its lashing out. Not all psalms are great poetry. We who read them, maybe we don’t expect them to be.

*

6:1 on the eighths The notation clearly has to do with eight, but what does that mean? The Vulgate says pro octava (Dahood 38), suggesting low pitch or complete scale. The NASB has “eight-stringed instrument.” Eighths could also count beats, syllables, or any number of things.

6:2 feel for me See 4:1 note.

6:3 my neck The word is nefesh, which, rendered as “soul,” gets my vote for the most significant poor translation decision.

6:4 turn back Shuv may be the most important trope in the Bible.

6:5 in death | there’s no memory of you The rhetoric here is audacious: “what good am I to you dead?” The Hebrew Bible, with the exception of part of Daniel, likely the last-written of its texts, does not have a vision of an afterlife that accords with most contemporary Jewish and Christian belief. There’s a shadowy underground, but neither a heaven nor a hell nor any detachable soul to survive a person’s death. All three of these concepts arrive in the Hellenistic context over several centuries.

6:6-7 with tears | I melt my couch The synaesthesia here is notable, despite the bathos: eyes too worn to see still generate tears, which speak with a voice the Lord can hear.

6:9 my feeling pleading The speaker returns to the appeal for pity and favor from verse 2.

6:10 blanch The word bosh does mean shame, but a kind that looks pale, coming from disapprobation, being a disappointment. There are other words in biblical Hebrew for the blushing kind of red-faced shame, embarrassment.