(rendition of David, which he sang to the Lord with the words of Kush the Benjamite)

* * *

While both can be classed as individual laments, Psalm 7 is a study in contrasts with Psalm 6. There’s less turning in this psalm, and no pleading for a change of heart or diversion of enemies. Instead of appealing to sympathy, the speaker names a threat (1-2), swears innocence (3-4), and calls on the Lord for legal intervention, a fair ruling (6-8). The rest of the psalm reflects on justice (the root tsadiq is used five times), a property it asserts is integral to God’s identity (6-11, 17). The psalm sees punishment as the fitting, even logical, outcome of meanness (12-16). Instead of begging God to be less angry, Psalm 7 demands God to remember who God is. Not “Lord don’t scold me | while you’re mad,” but “Rise, Lord | in your rage” (7:6a).

The psalm is at its most unique in the second half, from the end of verse 11 through verse 16, because of what looks like intentional ambiguity. From at least verse 8 to at least verse 11, the focus is on divine justice. By the time we get to verses 15 and 16, the focus shifts to the wrongdoer, who’s done in by the wrong he’s done. In between, however, in verses 12-14, there’s a remarkably blurred sequence of grammatically masculine verb forms and masculine noun suffixes with no named subjects: “If he doesn’t turn | his blade he whets / his bow he’s strung and readied” (12). If who doesn’t turn? Who sharpens whose sword? Who has prepared for whom “the tools of death” (13)? The English Standard Version tries to be helpful and clear: “If a man does not repent, God will whet his sword.” That’s a little like taping a photograph over a Cubist portrait. It misses the point. The bad man doesn’t turn. God doesn’t, either. The bad man sparks his arrows. God does, too. Double-duty pronouns depict the exact overlap of punishment and crime. The grammar may not be clear, but the significance is.

When I was in divinity school, I once misquoted a line from Elie Wiesel: “God made people because God loves stories.” I was trying not to use exclusionary language. My classmate Nina jumped in. “Yes, but you killed it. ‘God made man because he loves stories.’ We can’t tell who loves stories. It’s both/and.” It’s a cat and a vial of prussic acid, alone in a room for an hour.

*

7:1 rendition The word shiggaion is unknown and most often left in Hebrew. It might come from the root shagah, which has something to do with wandering off in one’s own direction. Some speculate that it means dithyramb. It could be an instrument, a style, any number of things.

7:1 Kush the Benjamite Not clear who this is. Kush is the name for Nubia and Ethiopia, Benjamin the tribal territory just north of Jerusalem (“between his shoulders he lives” Deut. 33:12), a region linked to David for being Saul country.

7:2 lest one slash my neck The slasher is unnamed but singular. As in other psalms, the word nefesh is often rendered “soul,” but refers to the vulnerable part of the front of the body.

7:4 stripped my attacker The word chatsal for stripping away means something similar to natsal, used in verse 1 and verse 2 (“whisk away”). “Attacker” is literally “one who binds me”

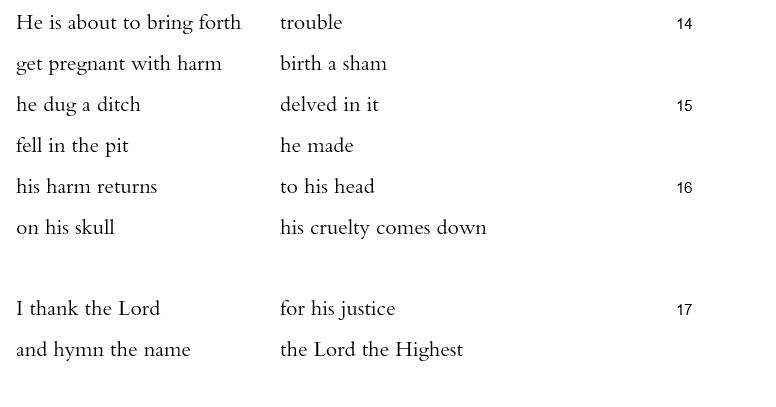

7:14 He is about to bring forth… The sequence is clear, and it’s vivid. He—more likely the bad man than God—is in labor: the hinneh-plus-verb formula generally yields a continuous tense. The verbs in the second half of the verse are in the vav + perfect form, which can result in either past or present tense constructions: “get pregnant with harm | birth a sham” is a leap that shows consequence as clearly as “sow” and “reap.” A wrongdoer is always in labor pains with trouble; impregnated by harm, he—that he is no she is the point—bears sham babies.

7:16 his harm returns This turning calls to mind Psalm 6, when read in sequence, but more immediately verse 12, “if he doesn’t turn.” If the villain doesn’t turn, villainy will turn on him.

7:17 Thank… hymn As an ending, the whole verse is kind of pat, but not necessarily added later. The verbs yadah and zamar are frequently paired.

7:17 The Lord the Highest The usual formulation of one of God’s names (or titles) is El Elyon, but YHWH Elyon works, too. This translation assumes that readers want to say something meaningful in English if they’re reading aloud or even mouthing these words. Saying the names in an old language has its own pleasures.