(director: on the Gath harp, lyric, of David)

* * *

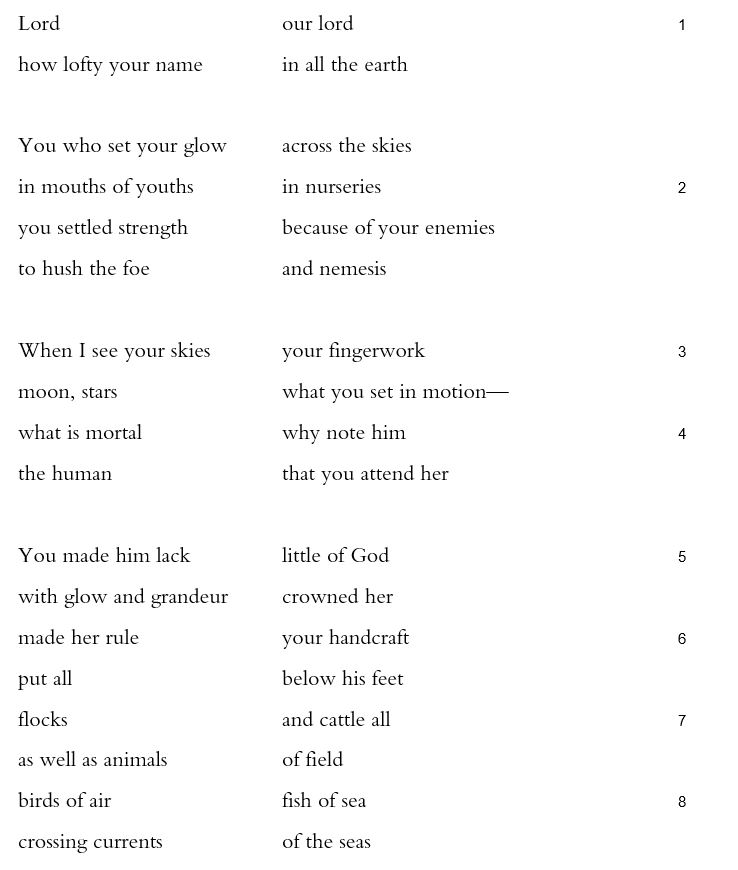

Among the strongest of all psalms, Psalm 8 is a tightly constructed poetic commentary on the beginning of Genesis. It starts and ends with a refrain that includes God’s personal name, yod-hey-vav-hey, a renaming of him as adonai, our lord, and an exclamation that is half a question: “how lofty / your name | in all the earth” (1, 9).

How lofty? We move from “your glow | across the skies” (technically verse 1c, though it belongs with verse 2) into the “mouths of youths” (2). (In the Bhagavata Purana, Krishna’s mother peers at the cosmos within her son’s mouth.) Verse 3 returns us to the skies with another half-question, half-exclamation—

When I see your skies your fingerwork

moon, stars which you set in motion—

—setting up the psalm’s key moment, the break, the aposiopesis, a Dantean moment of ineffability. In colloquial English, the speaker can’t even.

What follows this charged instant of rupture is first a double question that returns, for the second time in the psalm, to the small scale: “what is mortal | why note him / the human | that you attend her” (4). Then we’re lifted again to the heights: “You made him lack | little of God” (5). The back half of the poem sifts down through the days of creation in Genesis, through its version of a chain of being, from “below his feet” (6b) to the depths of the oceans, “crossing currents | of the seas” (8b).

This marvelously vertical poem may follow Genesis 1:28 in describing humans as putting other creatures underfoot, but its vision of the cosmos stresses the word “all,” used four times. It repeatedly interleaves the whole and the part, the large and the small. There are many ways to rule, many ways for that strength in the mouths of youths, for our human heft and grandeur, to note and to attend to the birds of air and fish of sea, ways that differ from those that now threaten their very existence. Surely the psalmist—at least—would grieve the loss of one of every four birds, nearly three of every four fish.

*

8:1 on the Gath harp Another unknown term, ha-gittit could mean “for the winepresses,” as the Septuagint suggests.

8:1 how lofty your name God’s name itself may be majestic, but “name” also signifies reputation, in both languages. The English phrase “the heights of fame” comes to mind.

8:1-2 You who set your glow… and the nemesis These are perplexing lines. The last third of verse 1 really does seem to belong here, rather than with the opening and closing refrain, though the grammar is awkward. The idea seems to be that the same Lord who set a “glow | across the skies” also created the human mouth as a potent weapon, though the mouth might figure breath or speech. More specifically, the strength that is fitted into the mouth might be the power of naming, which allows both the naming the Lord and the naming of the other living beings of earth. Even so, the three words “enemies,” “foe” and “nemesis” stress an antagonism that’s not picked up by anything else in the poem. Nahum Sarna follows Dahood in suggesting that these are references to “mutinous forces of primeval chaos” that are part of ancient Near Eastern creation myths (57).

8:3 When I see… The syntax is interrupted at the end of this verse, after the dependent clause (the protasis) only to restart with rhetorical questions as a different construction. The effect is like the English expression “what the—?” It deepens both verses.

8:3 fingerwork Very literally, “the work of your fingers”

8:4 mortal… him/ the human… her There are all kinds of ways to address the patriarchal language of the Hebrew Bible: carry every “he” over into English; try to elide grammatical gender with plurals and fewer pronouns; or change some pronouns to balance out the insistent masculine. This translation opts to minimize pronouns when that works, without changing singulars to plurals. When pronouns are needed, I have generally kept masculine pronouns for God, and for humans only when the masculine preserves some valuable ambiguity. Otherwise I attempt to use mostly feminine or neutral/third-gender pronouns in generic reference to humanity. Occasionally, as here, it made sense to shuttle back and forth. In a matter of years, this particular solution may seem archaic. The attempt is to acknowledge all.

8:5 lack | little of God It seems willful to translate ’elohim here, in a poem that starts and finishes with “your name” as anything other than God, which is what the word nearly always means. It can mean gods plural, or other divine beings.

8:5 heft The word kavod has an array of figurative, abstract meanings— from “honor” and “glory” to “dignity” or “worth.” The concrete meaning at its heart, however, is of heaviness, weight, a fullness, perhaps because to be large or loaded down implies having wealth and respect. Heaviness has different connotations in English, however. See introduction to Psalm 57.