* * *

* * *

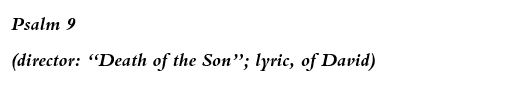

With Psalm 10, Psalm 9 is a broken acrostic, its contents shaped by both the form and its obvious ruptures. To take the second point first, this is not a well-preserved acrostic. Readers disagree about whether it is a single psalm or two, underemphasizing the more important point that what we have here are fragments, far more than two. If there are two groups of pieces here, it’s not quite Psalm 9 and then Psalm 10. The first goes most of the way through Psalm 9, then picks up again at the end of Psalm 10. The other makes up the bulk of Psalm 10, including… other verses?

Through the acrostic, the pattern appears to be four half-verse lines for each letter: aleph (9:1-2), bet (9:3-4), zayin (9:11-12), chet (9:13-14, maybe five lines), tet (9:15-16) and maybe yod (9:17-18), qof (10:12-13), resh (10:14, which is long), shin (10:15-16), and tav (10:17-18). Gimel and hey have two or three half-verse lines (9:5 and 9:6), while vav gets eight (9:7-10). Dalet, lamed, mem, nun, samech, peh, ayin, and tsade are all either missing or present but unrecognizable. That leaves 9:19-10:12, of which only 10:2-9 feels both cohesive and yet stylistically distinct.

As for the first point above, that Psalm 9 and 10 is/are limited by form, even intact acrostics tend to feel forced or choppy. It’s likely that acrostics played an important part in scribal traditions, teaching students passive content as they actively practice skills. As with other primers, hornbooks, elementary readers, and abecedaria across cultures, biblical acrostics tend to favor handwriting and piety over poetic risk. Not always. Poetic forms can encourage surprise as well as order, leading one away from what one merely wanted to say. Still, the best way to read these acrostics is probably Hebrew letter by letter, almost the way one reads a Japanese renga or Persian ghazal, looking for leaps across stanzas, one link at a time.

Aleph, for example, feels traditional. All four half-verses (lines) start with aleph, which in the first-person is easy to do. Bet introduces the theme—the bad will be punished because the Lord is a judge enthroned. Gimel and hey, which survive even though the dalet verses that should lie between them do not, follow the motif from bet, the leitwort, that the bad will vanish or “fade” (9:3b, 5a, 6c; compare 10:16). The vav verses return to the theme from bet, that the Lord judges from his throne.

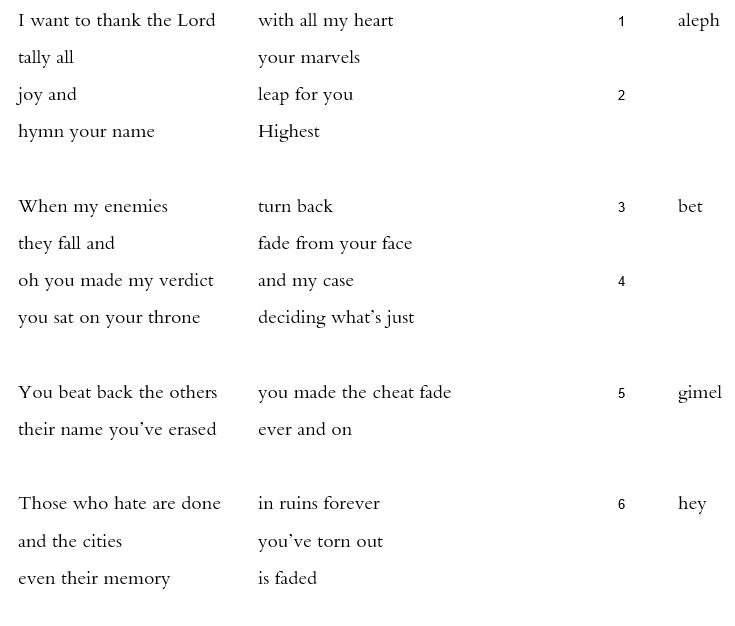

Yet from the punishment of the cheat, the verses turn to shelter for the weak, the theme that guides the acrostic from 9:9 through 9:18. In 10:2, the two sides of the same theme come together: “Conceited the cheat | stalks the weak / let them get stuck | in webs they wove.”

As the theme develops, the form slips, carried away by the most interesting verses of this one/these two psalms. Our camera tracks the bad person’s twisting paths. We hear his internal monologue, see inside his mouth, follow him into hiding. The effect is to take the relatively typical language of the acrostic— “he has not forgotten | the cry of the weak” (9:12); “do not forget | the weak” (10:12)— and splice into them the dramatic energy of a detailed scene:

he sits in waylay by the fences

in hideouts he slaughters the naive

his eyes on the helpless lurk

he waylays in a hideout as a lion in a lair

waylays to snatch the weak

he snatches the weak drawing him into his net (10:8-9)

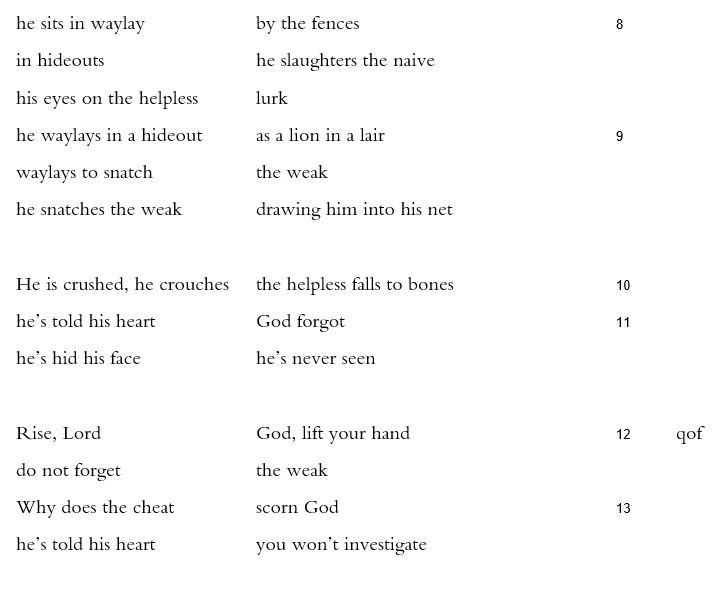

It’s possible, even likely, that the received text includes scribal errors, given the discontinuities, the lengthy interruptions of the form. And yet the breaks improve the psalm. So does that polyvalent blurring of pronouns right before the acrostic form resumes: “He is crushed, he crouches | the helpless falls to bones / he told his heart | God forgot” (10:10-11). Who is crushed? Who crouches? Who told whose heart that God forgot? The criminal, or the victim? Or both? The psalm looks for all the world like a broken-open seedpod, with something far more lively growing out from within.

* * *

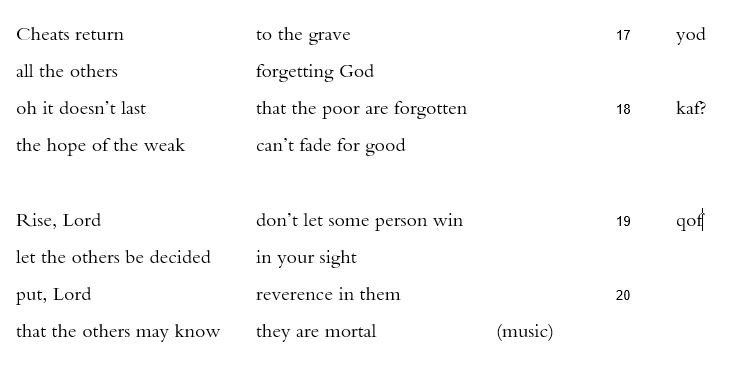

9:1 “Death of the Son” Literally this would seem to be the meaning of almut labben, which may be the name of a tune or some unknown musical cue.

9:2 glee and leap Typically paired (e.g., Ps 5:11, 68:3), the verbs samach and alats both describe celebratory actions, one a brightening, the other a dance.

9:4 decision… deciding The words mishpat and shophet. On campus once, I overheard two music composition majors talking. One said, “I showed him four measures I’d written and asked him what he thought I should do next.” “What did he say?” asked the other. “He said, ‘well, you can either repeat what you’ve written or write something new.’”

9:9 cliff fort A mishgav is a stronghold, yes, but the word “stronghold” doesn’t necessarily convey stone or heights, which are both visually valuable.

9:14 whirl in your rescue The common translation “rejoice in your salvation” treats the verb gil, to dance a circle, the way Michal treats David in 2 Samuel. Outside of a church or synagogue, who says “rejoice”? “Do a jig” is too casual, but closer: “rejoice” is disembodied and so uptight.

9:16 (loud music) The Hebrew is higgayon selah. This is a relatively wild guess.

9:19 Alter takes 9:18 as the beginning of a kaf section, which solves one problem but creates two more: then we have half a yod section and an overlong kaf section. Moreover the kaf section would have to begin with the ki that might make more sense as a conjunction within the yod section. An alternate possibility is a spelling error, assuming that the kaf and qof sounded as similar as they do now. Another alternate possibility is that, as in other places, textual transmission is just rough. Perhaps the most compelling alternative is that the break in the acrostic was intentional, though the intention is by no means clear.

10:3 it’s greed he’s bowed to The masculine pronoun here sets up the ambiguity of the cheat and the weak in verse 10 and 11.

10:4 with nose aloft “The pride of his countenance” works, but the literal Hebrew conveys the same idea so much more vividly.