(director: a lyric, of David)

* * *

Psalm 19 shows the potential and the limitations of collage. There are three main movements, each with two parts. The first movement (1-6) bears passing resemblance to an Italian sonnet— eight lines plus six, with a turn between. The second movement (7-11) also falls into two parts, with a striking change of topic. The final movement (12-14) shifts again, less dramatically, again with two parts. As with Psalm 18, the reader’s questions concern parallels and placement: why this with that? Why here? Why there?

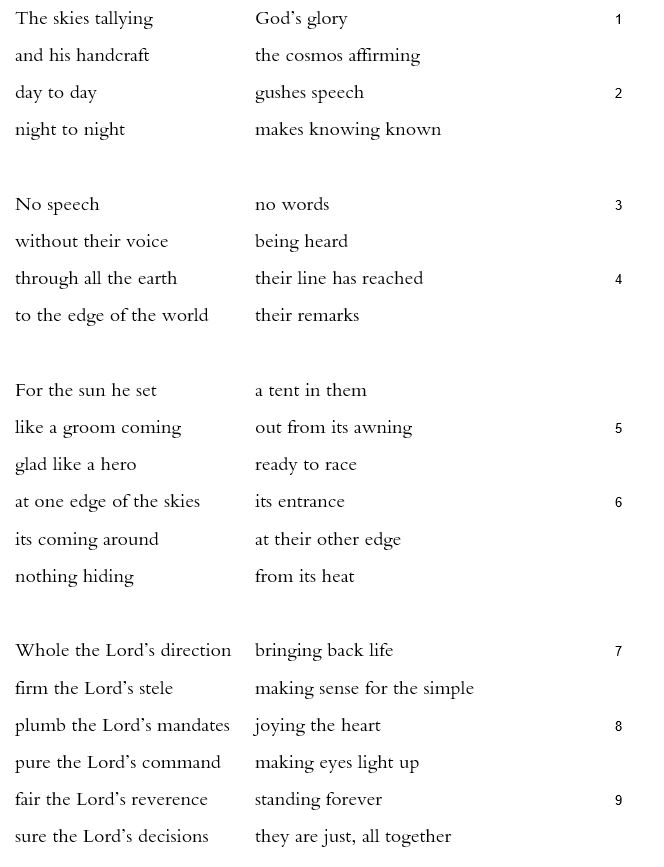

The first part of the first movement is transcendent, to me the finest block of four verses in the entire book of Psalms. It’s confident and terse, layered and profound. The first verse is virtually always rendered as two complete clauses. In the marvelous music of Haydn, for instance—those amphibrachs! those iambs!— it’s “The heavens are telling the glory of God; the wonders of his work displays the firmament.” While this reading is grammatical, technically the original text makes us wait until the second verse for a conjugated verb. The first verse is noun + participle + noun phrase, then noun phrase + participle + noun, the skies + tallying + glory-of-God, and work-of-his-hand + affirming + firmament. The verse is a perfect chiasm, a mirror form, each element having a partner.

To parse these constructions as clauses, we can easily supply an “is” or an “are,” since Hebrew doesn’t have a copula: the skies are tallying the glory of God; his handiwork is announcing the vault of the heavens, or, more likely, the vault of the heavens (in this translation, “the cosmos”) is displaying his handiwork. And indeed the verse does work this way, participles construed as the present continuous tense. But it also works, as written, to see the first verse as a sequence of absolute phrases, “the skies that tally God’s glory, the cosmos that proclaims his handicraft,” as a lead-in to the main clauses that arrive in verse 2.

Read this way, verse 2 hits hard on the explosive verb yabbia, literally “it gushes forth.” But what gushes? The text is ambiguous: days gush speech to other days? or speech gushes day to day? Read with verse 1 as two left-branching absolute phrases, there’s a third possibility: daily, all of this, the skies, God’s glory, the craft of his hand, the arch of the heavens, all of it gushes speech.

Either way, the gist is clear. The broad blue and clouds of day, the wide of black and starry night— it all speaks, the world pours speech, makes knowledge possible. The allusions to Genesis are evident, too: in the speaking by which God created the “heavens,” making the “firmament” on the second day of creation; and in those two subtle echoes of Eden at the end of verse 2. “Makes knowing known” mentions knowledge and slyly names Eve (Chavvah) inside a word that looks almost like the name of the Lord: yechavvah. The world is not just spoken into existence. It speaks. Knowledge comes not from a garden tree. It pours from the celestial dome.

After this beginning in which all is language and meaning, verses 3 and 4 stop us in our tracks. There is no speech. There are no words. It’s worth pausing there, at the screeching halt of the two negatives: literally, “no speech and no words.” Well, does the world speak or doesn’t it? Does it speak without speech? In the Analects, Confucius asks his disciplines, who had asked what they would pass along if he did not speak to them, “Does Heaven (tian) speak? The four seasons change, all things are born. Does Heaven speak?” (17.17). The answer is probably as yes as it is no.

Here in Psalm 19, in the second half of verse 3, the negative beli plays it both ways. “No speech | no words / without their voice | being heard” could equally be read as “No speech | no words / their voice | is not being heard.”

How long does this negation of the first two verses last? By verse 4, the claim of verse 2 returns: “through all the earth | their line has reached / to the end of the world | their remarks.” The “line” is a measuring line, but any line works: the firmament (see Job 38:5), the boundaries between nations (see 2 Kings 28:13), even the line of poetry (see Isa 28:10,13). The verb “has stretched,” y’atsa, shows up in verse 4a in an exact parallel to the verb “gushes” in verse 2a. Gushing and stretching are, with “makes known,” the only conjugated verbs in the first four verses (4b is yet a third absolute phrase, and 4c properly belongs with verses 5 and 6). Thus in the verb position these verses are all in motion, motion outward, motion in excess, pouring out and announcing and pushing out, while language and speech are absolute and everywhere, then nowhere, then everywhere again. It’s a tour de force.

The sestet to this octave begins with 4c and continues through 6, in a passage that focuses on the sun. The setting is still in the skies, but apart from a few verbal links (“edge,” qatseh, for instance, shows up in 4 and twice in 6), everything else is different, theme and tone especially. This second part of the psalm’s first movement is more clever than profound, the sun compared to both a bridegroom and an athlete, culminating in what seems like a joke: “nothing hiding | from its heat” registers the sun’s warmth as well as the athlete’s as well as the groom’s ardor. There is no trace of the deeper concerns of the first four verses, the surplus of meaning in a world that everywhere speaks. Why these lines, here? Why move from the speech of the skies to the coming and going of the sun?

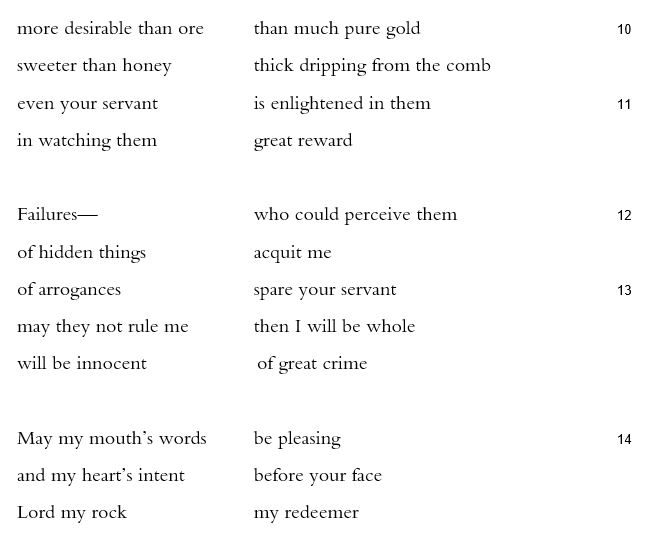

Everything differs again in verses 7 through 9, the center of the psalm. It’s customary to read this psalm as having two sections juxtaposed—one on the book of nature (1-6), the other on the book of the law (7-14). But it’s busier than that, since only 1-4 and 7-9 (maybe 7-10) explicitly take on nature’s language and God’s. Verses 5-6 and 11-14 take us elsewhere. This central section, for its part, indeed concerns the law, but not the Torah that comes eventually refer by extension to the traditional five books of Moses, or the whole Hebrew Bible, or the whole Bible including the Oral Torah and the entirety of Talmudic and rabbinical tradition. Rather, the torah that leads this list of synonyms for instruction is both larger and smaller than that later concept of Torah. It’s all instruction, in and beyond the biblical texts and traditions. Torah is first in a list of six kinds of rules—why six? the six days of creation? to ensure that the psalm names the Lord seven times, including verse 14? This list is shaped, too, around six iterations of the divine name, six traits (two singular, one plural; two singular, one plural), plus six participial phrases (one of these participles is a trait: emunah in 7b).

As with the first part of Psalm 19’s first movement, participles lead to a single conjugated verb. Here “justice” is the verb. Thus, all of this, all of these rules doing these things, “they are just, all together” (9b). This structure, all these absolute phrases, powerfully allows verse 9 to recreate the effect of verse 2 and of verse 4, energizing the main verbs even as it allows that “all together” to embrace more than the laws of 7-9. All the Lord’s direction from standing stone (`edut, cf. da`at “knowledge” in verse 2) to verdicts, show justice, plus the skies and all they say. Like the skies, laws speak without speaking, but nothing speaks without them. And yet, while the skies burst forth with sense, language, and knowledge, note how motionless the Lord’s instructions are: “whole… firm… plumb… pure… fair… sure” (7-9). It is reasonable and resonant to pair 1-4 and 7-9, passages that artfully complement one another.

What troubles this tidy concept, however, are all the psalm’s other parts, not least of which is that passage about the sun. How does that passage affect what comes before and what comes after? Does the sun figure the speech of the skies, or the Lord, or the Lord’s justice? Is its motion across the sky linked to “the Lord’s command | making eyes light up” (8)? That seems a stretch. We bump now against the limits of collage. It makes sense to juxtapose, to ask questions, even at times to overwhelm us with questions. If everything speaks, it’s hard to hear.

The next parts of the psalm, how do they fit? Verses 10 and 11 are also constructed around participles rather than main verbs. Like 9b, they have an open-ended “them” (11, x2), desirable and pouring forth honey from the comb. This seems to refer directly to the Lord’s commands and potentially again/still the skies.

What about the turn in verse 11 to the speaker, “your servant,” which carries through to the first-person person supplication of verses 12-14? Is this a kind of parallel to the singular “sun”— that is, an elaborate analogy, the speech of the skies : sun :: law : your servant? If so, then the third movement returns to the first, but with different angles, different themes. Note that the speaker’s “hidden things” (minnistarot, 12) recall the “nothing hiding” (velo nistar, 6) of the first movement. Perhaps even the use of mashal “to rule” picks up the role of the sun in Genesis 1:16 “to rule the day.” This is guesswork, for the collage work has grown strange. What are these failures, these hidden things, these arrogances the speaker wants to be exonerated from? Why here? Do they relate to the six kinds of divine command? To the sun’s constant motion? To the burst line of cosmic speech?

In the last verse speech returns to the poem: “may my mouth’s words | be pleasing.” This is a far cry from where we began.

Nothing against psalms that raise more questions than they answer. Nothing against oblique angles or puzzles that exceed our grasp. It’s possible to overthink things, maybe, wondering what sun and servant are doing in this psalm. If we end with questions, it’s only because the verses that start Psalm 19 are so strong that they make it seem impossible to overthink anything ever, so surfeited with significance is the world.

*

19:1-3 The skies tallying .. being heard See introductory note above.

19:4 their line has reached In Jeremiah 31:39, a surveyor’s “line” “reaches,” which is likely the most literal meaning here. But the association of lines with speech— divine speech, perhaps without sense— appears in Isaiah 28:9-13 as well.

19:4 For the sun he set A stanza break here emphasizes the etnachta under “their remarks” in the Masoretic text, a break that downplays the squinting of the syntax. In other words, the line “their remarks to/for the sun” is a grammatical possibility made less likely by punctuation. The question the reader has to ask is how the sun is like a tent in “them”— in those plural remarks, or the skies of verse 1, or the speech and knowing of verse 2.

19:7 Whole the Lord’s direction… firm the Lord’s stele In Leviticus (e.g., Lev 4:28, 32) and Numbers (e.g., Num 19:12), the adjective temimah (“whole”) describes the intact body of a herd animal to be sacrificed. The body’s completeness, its entirety, is here applied to the entire torah (“direction”), with the ranging reference of that word. The word `eidut, for its part, refers most specifically to something contained (Exod 40:20) in the Ark of the Covenant (sometimes called the Ark of the `eidut, as in Exodus 30:6) or in tablets of the law (e.g., Exod 31:18). By metonymy, the word refers to the entire tabernacle (Exod 38:21), to its veil (Lev 24:3), or to the body of the law itself (e.g. Ps 119). The English words “witness” and “testimony” do reflect the Hebrew derivation, but they don’t convey the solidity of the thing that is meant. Moreover, to some communities, they connote particular kinds of practice, enthusiastic, first-person, autobiographical, which to me makes them unusable here. It may be somewhat fanciful to translate `eidut as “stele,” the kind of standing stone that existed throughout the ancient world. But such stones bore inscriptions and laws and took on ritual value (see Exod 16:34 and 2 Kgs 11:12). “Stele” seems to me to maximize reliability and firmness, which are clearly what matter.

19:10 thick dripping from the comb It’s hard to express how lush this is in Hebrew: venophet tsuphim, so forward in the mouth. The two root words, nuph and tsuph, convey such movement and flow.