(of David)

* * *

All poems and hymns are composite, whether they seem the work of one hand or many. Lines and stanzas take different angles. New images complement or challenge old ones. Abstractions butt heads. It would be valuable to be able to know whose hands—whose eyes, whose ears—put which pieces where and when, who arranged Psalm 25 to mirror Psalm 34 with Psalm 29 in the middle. And to know who paired Psalm 27 and Psalm 31. It would be nice to know which seams within psalms were intentioned by authors and which by editors— if there was even a difference. And yet the whole exercise, trying to find which parts were made by whom, is fraught with logical circles.

As an instance of this unknowable intentionality, Psalm 27 relies on a curious shift. In reductive applications of form criticism, it is often called a psalm of “trust,” as if one word could convey a theme, let alone a genre. The whole psalm, it should really be said, pokes at the tissue of trust. It presents a psychologically rich portrait of trust being torn and repaired, with layers of bravado and vulnerability and dread. It’s a therapist’s stomping ground.

The psalm begins with a doubled question of identity, a move seen before in Psalms 15 and 24. The questions in Psalm 27—not about who, but “of whom” should I be afraid?—become more than rhetorical. Verses 1-3 sound like bluster. Given that the Lord is my fortress and light, the zombie-like horde of villains who pile up in verses 2 and 3 are met with two statements of calm: “my heart does not fear… through this I lean back.” The word betach, the most common biblical word for “trust,” relies on an image of relying on, of reclining in peace. The picture of a teambuilding trust-fall comes to mind, or of carrying children off to bed.

From leaning, however, the psalm turns to images of sanctuary. Verse 4 is a strange leap after confidence, the sudden wish to live in the temple, a movement clearly marked as a retreat:

For he hides me in his den on the bad day he conceals me

under cover of his tent to a cliff uplifts me (5).

There are three locations here, at least two of them metaphorical— the Lord’s tent, likely literal, flanked by an animal’s burrow or warren or den, which goes down, and a cliff to which the speaker is “uplifted” seemingly within the tent. From safety, within the tabernacle or temple, above the enemies, the speaker offers song. But how does this retreat from threat relate to reclining in trust? The psalm has moved from confidence to concealment.

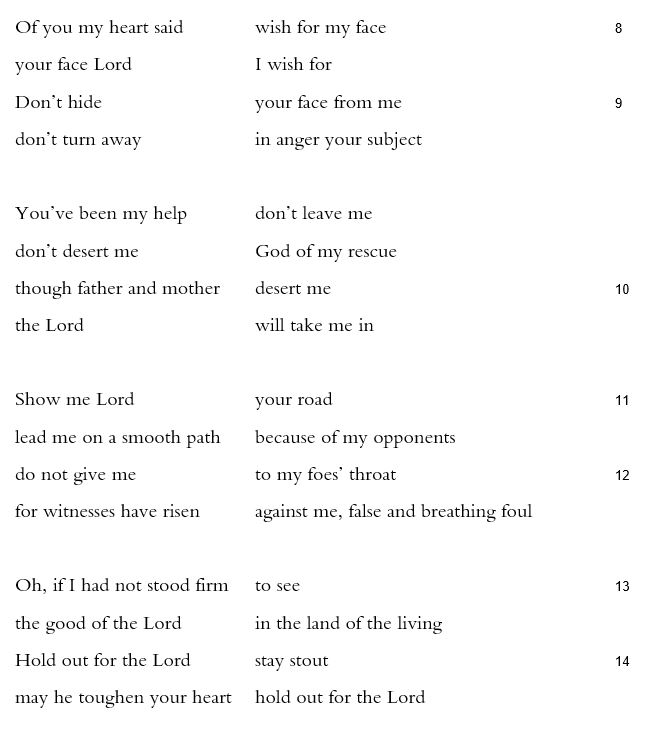

Once the psalm shifts to first-person address, the image of hiding returns. In the song that the speaker sings, rather than narration, we hear a complicated desire and plea:

Of you my heart said wish for my face

your face Lord I wish for

Don’t hide your face from me

don’t turn away in anger your subject

You’ve been my help don’t leave me

don’t desert me God of my rescue

though father and mother desert me

the Lord will take me in (8-10).

That wish in verse 8f or the face to stay—literally “seeking” the face— is particularly blurry. A vulnerable sentiment is expressed: Look for my face, Lord! I look for yours! Is that “trust”? Having voiced confidence in the face of armies, the speaker is whisked into sanctuary, whereupon she sings this song of what smacks of desperation: “don’t hide… don’t turn away… don’t leave me / don’t desert me” (9). You don’t need a counseling degree to want to ask a follow-up to verse 10: “though father and mother | desert me / the Lord | will take me in.” Tell me more about your parents…?

Maybe the hiding doesn’t last. The final four verses anticipate movement away from shelter: “Show me Lord | your road / lead me on a smooth path | because of my opponents” (11). How curious, then, that the psalm ends with the speaker waiting. The word qavah means to be expectant, to hope, to gather while waiting.

But it’s not just waiting. The final verse is a first-person address to some second-person singular who is not the Lord. That “you” might be liturgical, to be sure, one worshipper to another: “Hold out for the Lord | stay stout / may he toughen your heart | hold out for the Lord” (140. But within the poem, this reads more like someone psyching herself up. A declaration of trust at the beginning has transformed, gone vulnerable, grown up, gone deep. Here at the end that trust has become a kind of self-encouragement, far removed from a naïve trust fall. But then, maybe trust is hope or holding out, a mirror scene of telling yourself to stand firm, stay strong.

*

27:5 in his den A figure for the tabernacle, to be sure (e.g., Ps 76:2), the word is also used for the shade where lions lie (Job 38:40).

27:8 Of you my heart said | wish for my face An example of the tremendous power of preserving ambiguity. Most translations deploy quotation marks and reverential capitalization of “my” here to read “wish for my face” as the speaker citing God’s desire for the speaker to seek God’s face. But it is also possible to read the line more simply as the speaker’s desire to be sought. The more common idiom understands the speaker to be beseeching the Lord—as indeed happens in the second line of the verse: “your face Lord | I wish for.” But this line admits the opposite as well: the speaker also wants to be wanted. See also the introduction to this psalm.

27:13 false and breathing foul The meaning of vipeiach, a hapax legomenon, is uncertain.

27:13 Oh, if I had not stood firm | to see The word lulei is counterfactual, “unless I had stood firm,” which makes literal translation unsatisfactory. Some translations supply a “then” to complete this line’s “if not” clause: for example, “[I had fainted] unless I had believed” (KJV). The emotive power, however, comes from not knowing or not stating what would have happened.