(of David)

* * *

There has to be a least interesting psalm. Psalm 28 volunteers. Full of circumlocutions, abstractions, and cleverness, its petty moral sensibility leaves readers little to reward attention. It reads like a wordy elaboration on the first verses of Psalm 18/2 Samuel 22: “my cliff” (28:1, 18:2), “my strength my shield” (28:7, 8; 18:1, 2), “the stronghold” (28:8, 2 Sam 22:33).

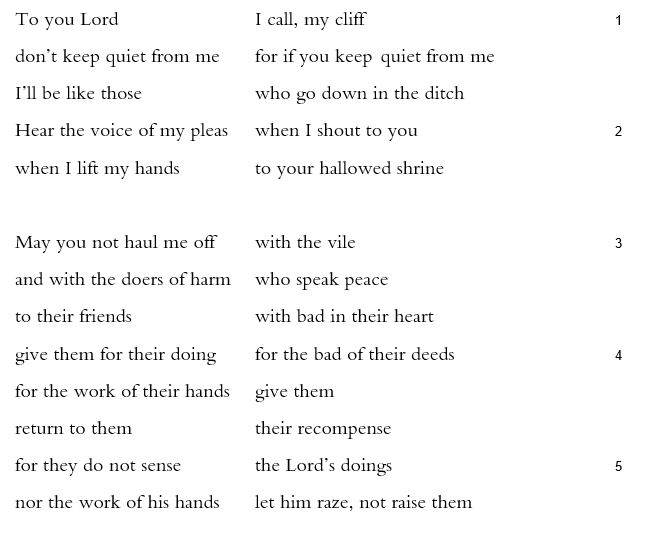

What is it that the speaker wants? Having worshipped, she calls for a response: “hear the voice of my pleas | when I shout to you / when I lift my hands | to your hallowed shrine” (2). What kind of pleas are these? “May you not haul me off | with the vile” or with those who make trouble or those who “speak peace… with bad in their heart” (3).

Other psalms provide passionate evidence of the trouble the “I” is in. Other psalms call for justice that would prove the speaker’s innocence, or tug at the Lord’s pity, or remind him of his fidelity and care. This speaker speaks instead in a coy second-person imperfect—not the imperative. Rather than demanding with a full-throated imperative, not to be lumped in with the bad, she speaks indirectly, deferentially, “may you not” (“you do not” is possible as well).

Worse, instead of justice for herself, she seeks punishment for wrongdoers in general, not anyone who has specifically wronged her:

give them for their doing for the bad of their deeds

for the work of their hands give them

return to them their recompense

The language is generic, not to mention repetitive. Parallelism can do so much more! It can intensify, clarify, deepen, map. What does “give them” add the second time? How does the cliché “the work of their hands” focus or adjust “for the bad of their deeds”? Maybe there is a matching here, the three kinds of bad in verse 3 matched with appropriate retribution? But nothing is specific about either the crime or the punishment. “I have worshipped, so please don’t treat me like those awful people who get what’s coming to them?” The piety begrudges; it grates.

These central moments of the psalm are led and followed not by details, but by puns. The bad do bad (ra`ah) to their friends (re`eihem) in verse 3, which is similar wordplay to Psalm 23 (see note to Psalm 23), though this pales in comparison with that, in range and significance. In verse 5, the play is somewhat stronger, ki lo‘ yabinu, “because they do not sense,” which is met by velo‘ yibneim, “he shall not build them up.” But what doings of the Lord has the psalm asked the reader to sense?

Read Isaiah 1, I want to tell the speaker, whom I feel sure I’ve met before.

*

28:1 don’t keep quiet from me A very literal rendering of the Hebrew idiom, which describes not just any kind of silence, but privation or secrecy.

28:3 May you not haul me off The verb mashak does not necessarily suggest a formal register, though the verb’s conjugation in the indicative makes it more polite than the imperative would have been. Some readers may find this translation too informal, others may think it too formal. That tension is in the Hebrew.

28:3 their friends | with bad A Hebrew pun, as the introduction to Psalm 28 points out: re`eihem ra`ah enacts the corruption of friendship.

28:5 let him raze, not raise them The pun in the verse actually pairs velo’ yibneim “not raise them” with ki lo’ yabinu, “for they do not sense.” In the Hebrew, then, the etymology suggests that the Lord’s refusal to establish the bad is rooted in their failure to discern. This translation’s pun gives only the flavor of the original.