(lyric, a dedication song for the house of David)

* * *

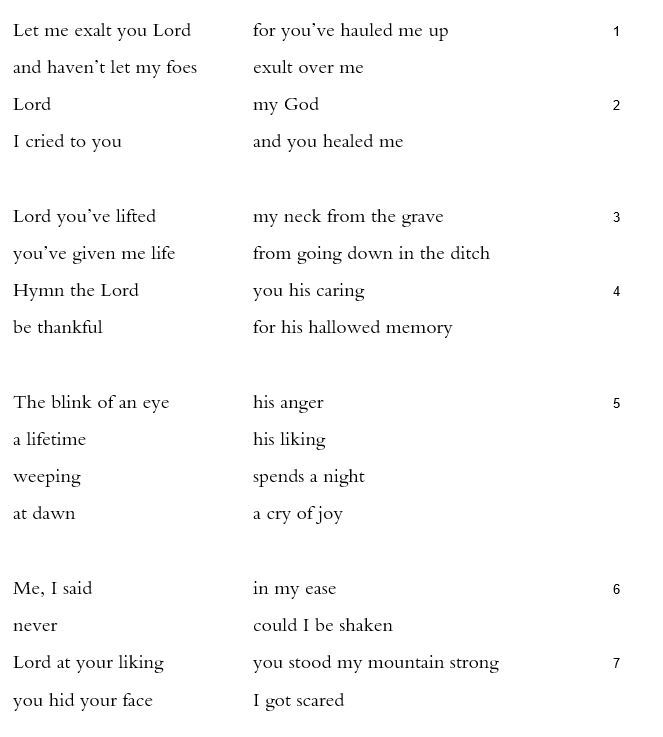

A defining dynamic of lyric poetry runs between the speaker’s world and the reader’s. One I speaks, many I’s read. As I recite, “Lord | my God / I cried to you | and you healed me” (2), there is a tension. I am not actually the speaker of Psalm 30 and yet, through a range of possible responses, I come to identify with her, pulling her close, or evaluate her, holding her at arm’s length. This dynamic of identification and distance allows for absolute immersion—how many people over millennia must have said, deeply personally, “I cried to you | and you healed me,” in how many languages. Yet at the same time, that lyric “I” allows for scholarly critical analysis: who is she, where, when, how, why, even whether?

In Psalm 30, this general readerly dynamic is stretched even farther in one direction by the context, a public commemoration in or of the temple, and by the opposing pull of the psalm’s many appeals to private feeling. Psalm 30’s superscription and the plural imperatives of verse 4 tug our experience of the psalm towards the ceremonial and liturgical, a collective historical memorializing that dedicates the “house of David” through the singing and worship of the chasidav: “you, his caring / be thankful | for his hallowed memory.” Which house of David? The dynastic line? Solomon’s temple? The Second Temple? How different this psalm looks without the superscription or without verse 4.

On the other hand, most of the psalm is shaped around either pleading for or gratitude for healing. Healing from what we don’t know, but not knowing tips us towards identification. No single narrative sequence is clear, but the speaker seems to have felt confidence (6-7a), then fear (7b), which has led to pleading (8-10). Injury or desperation is figured as the edge of death, in a pair of verses that refer to the pit or “the ditch”: “what good is my blood | if I’m going down in the ditch” (9); “you’ve given me life | from going down in the ditch” (3). Other verses reflect on the experience of healing, which the psalm presents overwhelmingly as a fait accompli (1-5, 12). Being healed results not from the speaker’s innocence or goodness, nor even from the speaker’s fidelity, but from the pathos that is the Lord’s fidelity. The Lord likes the speaker. “A lifetime | his liking” is complemented by “Lord at your liking | you stood my mountain strong,” both times the word ratson (5, 7). And the Lord feels. The root chanan appears twice as well, in “plead” (8) and “feel for me” (10). The terms touch, each translatable by the word “favor,” though the word rendered here as “liking” has more to do with pleasure, while the second is more like pity, compassion, one’s heart going out to someone.

This psalm, then, is not a singular thing. What song or poem is? It is instead a dramatic range: quiet begging, communal celebrating. Holding it far enough away to see it through lenses of curiosity or analysis, we notice how it personalizes collective memory in an experience of gratitude, how it makes feeling-better recapitulate liturgical practice. Coming close enough to identify with or feel like the speaker, we are brought near a near-death experience to join the joy of the morning, “weeping | spends a night / at dawn | a cry of joy” (5). And reading somewhere between assessment and absorption, we are able to sympathize. Maybe most dramatically, in so doing, the role we take on is the Lord’s: “Hear Lord | and feel for me” (10).

*

30:1 exalt… exult As with “hauled” and “healed,” this instance of verbal play is not in the Hebrew. This particular poem’s own connective devices (or moments of pleasure) are harder to replicate—the semantic alignment of verbs on the vertical, the play of ’elohei and ’eilekha, “my God” and “to you.”

30:4 be thankful | for his hallowed memory It’s not clear what it means to thank or praise, literally, “the memorial/memento of his apartness/holiness.” Possibilities include a specific object of ritual value and cultural memory, a personal memory the speaker has, or the act of gratitude itself, which recalls as it gives thanks.

30:5 The blink of an eye.. a cry of joy A treasure of a verse, both for the precision of its oppositions and for its potent hope, this aphoristic quatrain maps bodily images of sorrow and anger, pleasure and joy, against experiences of different duration. The NIV waters down the poetry, supplying four verbs for a verse with only one.

30:7 I got scared This stanza (verses 6-7) reverses the preceding one. Instead of moving from grief and divine wrath to divine favor and joy, it moves from ease and favor to the speaker’s being “shaken” and frightened by God’s disappearance. Parallel to the false sense of security in verse 6, this second half of verse 7 relies on a verb + participle of process: literally, “I became frightened.”

30:11 my keening The context is obviously not Irish, but the Irish caoineadh means much the same as the Hebrew mispeid (here: mispedi), the crying out for the dead.

30:12 so respect might hymn you In a curious circumlocution, the speaker imagines the music of praise from either the Lord’s kavod, or his or her own, or from glory itself.