(of David, didactic)

* * *

This psalm is several fabrics held by delicate stitches. It is a careful chiasm, with hallmarks of wisdom literature as its A-A’ frame (1-2, 10-11), a fascinating B-B’ second frame that pairs suffering with the bridling of a horse or mule (3-4, 8-9), a C-C’ third paneling of prayers of confession and praise (5, 7), and a center, X, verse 6, that is as precise as it is profound.

It makes sense to start in the center. The syntax is complicated enough that translations routinely misunderstand it:

Thus prays to you each of the caring

in the moment of finding for sure in a flood

that mighty waters will not touch him (6).

It’s that “moment | of finding,” literally “the time to find,” that confuses, leading the KJV and its descendants to some version of “a time when thou mayest be found.” That reading requires grammatical invention, adding a “thou” and inverting the infinitive from active to passive stem. More problematically, it also means giving God office hours: at what time may God not be found? Siesta? But the “finding” makes far more sense, literally, grammatically, and theologically, as adiscovery of the chasid, the devotee, the one caring and cared-for. The verse insists that some prayers are uttered when cataclysm threatens, others in perfect calm, and still others— these— are delivered in that instant when what has threatened recedes. It’s the exact moment of the Kantian sublime, a precipice moment, when imminent danger, just thwarted, reconstitutes the transcendental subject. But given that this is a moment of prayer, it is not Reason that reveals its constitutive powers, but divine care.

But which “Thus prays to you” is this prayer? The prayer before verse 6’s moment of flood or the prayer after? Or even the prayer during? At the center of verse 5 is a confession: “I said let me admit | my crimes to the Lord.” The sense of verses 5 and 6, then, seems to be that the caring one admits wrong when disasters have just been averted (in an experience that calls to mind William James’s observation that the feeling of silence is the feeling of thunder just gone). Or, the caring one prays thus, in verse 7: “You my secret from stress | you keep me / with shouts of escape | you embrace me.” Having been saved from a deluge, the caring one offers not confession but gratitude and a marveling embrace. It’s even possible to read verse 6 as saying that, in the moment of finding oneself in a flood, each of the caring prays to the Lord thus: “that mighty waters | will not touch him.” The “thus” is thus potent. It reverberates with meaning.

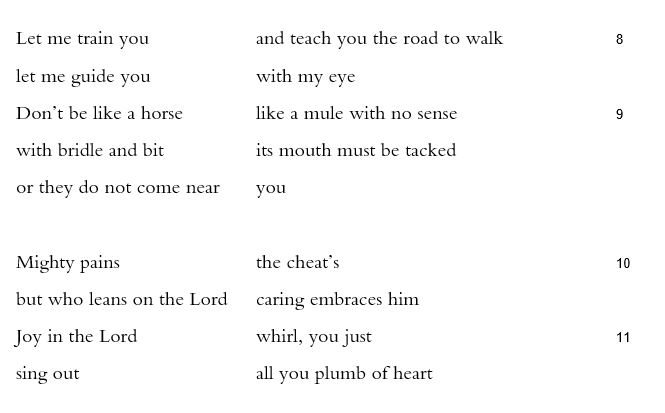

The B-B’ frame, in verses 4-5 and 8-9, presents not prayer but quiet. The earlier verse pair describes the speaker’s suffering, dramatically and uniquely: “your hand weighed on me / my chest turned over | in the fevers of summer” (4). Through this pain, the speaker does not speak, but groans: “Oh I’ve kept quiet | my bones have worn out / with moaning | all day.” In the later verses, silence returns not as reluctance or inability to speak, but as a taming. The “I” of the first part of the psalm is now a “you,” addressed either by God or someone else: “let me guide you | with my eye” (8). This line is followed by an actual bridling. “Like a mule with no sense / with bridle and bit | its mouth must be tacked” (9).

At the psalm’s two ends, its opening and closing, the three vocal prayers of the psalm’s middle, plus the two kinds of silence, are all held together between “breath” (2) and singing— “sing out | you plumb of heart” (11). That chiasm works not just formally, from outside to inside, further inside to center, but narratively from start to end. We move from breath to quiet groans to, finally, confession, a movement followed in the second half of the psalm by praise, “shouts of escape,” a disciplined mouth, and a culmination in song.

Along the way, repetitions and symmetries stitch the piece together. The language of verses 1 and 2 is picked up by verse 5: “fault” and “suppress.” The hand that “weighed on me” (4) becomes the “eye” that guides (8). The nearing of the waters in verse 6 becomes the nearing of the bridled horse in verse 9. And in verse 10, caring returns from verse 6, together with the particular stem of the verb for “surrounding,” also used in verse 7. Each time it means “embrace.”

*

32:1 didactic It’s not clear what makes one psalm more instructive than another, but the root of the word maskil, which appears in the superscription of thirteen psalms (here and Pss 42, 44-45, 52-55, 74, 78, 88, 89, and 142) has to do with developing wit or wisdom or skill. It makes little sense to leave this word untranslated: its semantic range is clear, even if its meaning in context is not.

32:1-2 crime… fault… wrong… guile Ringing the changes on “wrongdoing,” the opening stanza leads from pesha` to chata’ah from `avon to rimiyah. If the term “didactic” indicates a psalm that’s teachable, the arrangement of these terms provides food for thought and fodder for discussion. Like the progression of synonyms at the start of Psalm 1, which also begins with “all set,” these terms move from the outside in, from action to intention. There may be other organizational principles at play as well.

32:4 my chest turned over | in the fevers of summer Neither “chest” nor “fevers” is at all certain. The word leshadi may consist of the first-person singular suffix attached to leshad, a word used elsewhere only in Numbers 11:8, likening the taste of manna to oil. Or leshadi could be parsed as first-person singular suffix, the directional or possessive preposition l-, and the word shad for “breast.” The expression becharbonei qayits, “the fevers of summer,” seems to refer to either drought or rot. Since the word leshad may have to do with juiciness and qayits means “summer fruit” as well as “summer,” the speaker is experiencing a kind of disrupted fertility, an inward sickness.

32:6 in the moment | of finding … will not touch him Dynamic translation, for all its merits, loses the experience of following syntax as it unfurls, word by word. See the introduction to this psalm.

32:7 from stress | you keep me There’s a deft pun here: mitsar titsereini. The word for danger or a foe, tsar, is followed by, even absorbed in, natsar, to protect.

32:9 must be tacked The verb balam appears only here, but its meaning seems clear.