(of David, at his scrambling of sense before Abimelech, so that he exiled him and he went)

* * *

The superscription of Psalm 34 is particularly sharp. In 1 Samuel 21, David’s north-northwest madness in the court of Philistine King Achish (whose title may have been Abimelech, “my father is king”) allows him to escape unscathed. Narratively, David’s deception of Achish foreshadows his later acts of double agency in 1 Samuel 27, when he pretends to fight for the Philistines while gathering power in Judah. At the same time, David’s duplicity becomes a defining character trait. His feigning shapes how we read his every future move, from the killing of Saul to the killing of Uriah to the killing of Joab. Before we read a line of Psalm 34, we wonder if the king knows a hawk from a handsaw. The “scrambling of sense” in the superscription also reads like an apology in advance for a psalm whose turns are sometimes baffling. Or it reads like a taunt: though this be madness, is there yet method in it?

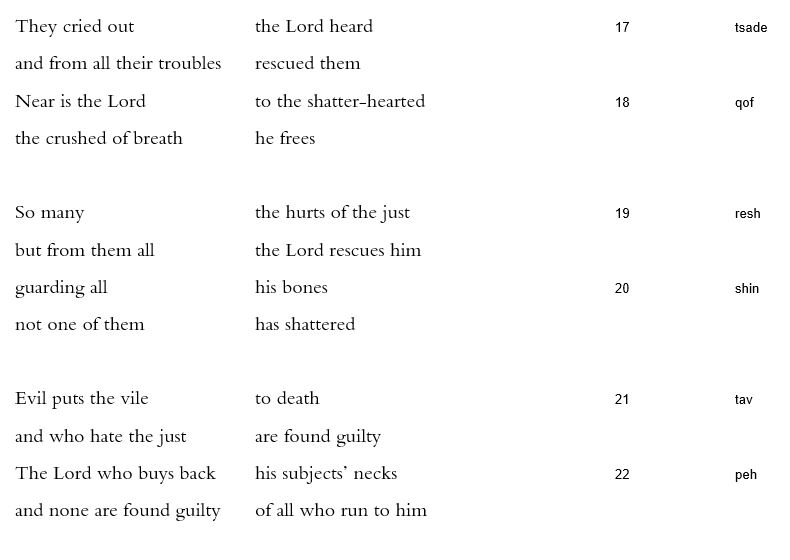

There is clearly method. An acrostic psalm of 22 verses, Psalm 34 lacks only a vav for the complete aleph-bet, and all the lines are of normal length. The second half of the poem is as unified as an acrostic can be. Verses 11-14 work as a unit of instruction, with imperatives in 11, 13, and 14: “Come, children… hear me… keep your tongue | from the bad… seek peace | and chase it.” Though the next two verses shift to third-person narration, they pair well with the tongue and the lips. “The eyes of the Lord | are on the just / his ears | on their cry for help / the face of the Lord | at those doing bad” (15-16a). The “they” who “cried out” in verse 17 leaps from “those doing bad” to “the just,” given that “the Lord heard… and rescued them.” But our confusion is momentary, even rewarded by the next verse which gives detail about “the just”: “Near is the Lord | to the shatter-hearted / the crushed of breath” (18). The last four verses of the psalm, including the out-of-place peh verse 22, continue the theme of the Lord’s protection of the just (19, 21).

It’s the first half of the psalm that seems, if not madness, at least a disguise. Wisdom hides in thanks, or vice versa. The poem starts in the first person, with enthusiastic praise: “Let me kneel to the Lord | all the time / endless | his praise in my mouth” (1). Verse 5 gives pause. “They have looked at him | and gleamed / but their faces do not blush.” Who have looked? At whom? The “poor,” last mentioned in verse 2? Surely not the “terrors,” the most recent plural noun. Why do their faces not blush? Is this a way of saying that the humble have been taken care of? Verse 6 starts with “this poor one.” Is this a singularization of the ones who looked at him and gleamed? Does “this poor one” equal the I of the first four verses, the first-person masquerading as third-person? Would the missing vav verse between 5 and 6 have clarified things?

What about the messenger in verse 7, “who encamps all around / the ones who revere him”? When this messenger bears away the reverent ones, is this how the Lord rescued “this poor one”? And how do we get from there to the sense of taste in verse 8: “Sense and see | how good the Lord”? Or from this first half of verse 8 to the second half: “all set, the hero | who flees to him”?

There is a logic here, it’s true, in the broadest sense: the Lord has taken care of “this poor one,” who may be both the first-person speaker of the first four verses, and one of “those who revere him” and “the hero | who flees to him.” Our confusions may be on the surface. Words that repeat multiple times such as “all” (8 times)” and “revere” (4) begin to pull the whole experience together.

Perhaps what makes it seem most unified are some of its lightest touches. The word ta`am appears in the superscription as the “sense” that David has disguised, then returns in verse 8 as the sense in “Sense and see.” The word in verse 2 translated as “goes crazy,” tithallel, comes from a reflexive intensive stem for the verb that means praise, which shows up in the noun form in verse 1: “his praise,” tehillatov. Reflexively, it means something like praising oneself or boasting. In another reflexive intensive stem, different in the vowels but not in consonants, the verb means to be out of control or insane. One place it appears is, not coincidentally, 1 Samuel 21:14, to describe David’s feigned madness. The doubleness of praise and madness is followed by the doubled response of the poor (the weak, the humble) who hear (yishma’u) and are glad (yismachu).