(of David)

* * *

In this psalm, everything depends on who speaks. If, as it seems from several verses, it’s one who’s been falsely accused, then Psalm 35 depicts desperate indignation and the desire for justice. “There arise | vicious witnesses,” the speaker says in verse 11. This reading fits the actions and speech of verses 19-21. The “lying foes / who baselessly hate me | they wink an eye” (19). Against the one being framed, these fraudsters have claimed falsely—complete with villainous exclamations— that “our own eyes | have seen” (21). Opposed to these winking and lying eyes are the eyes of the Lord, who sees rightly: “My lord | how much do you see” (17) becomes “You have seen Lord | don’t be silent” (22).

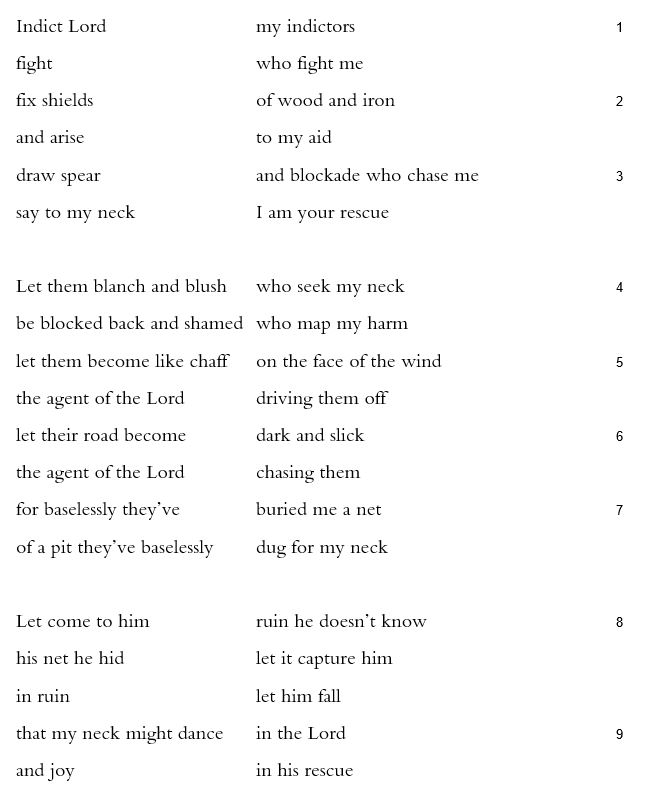

Other verses, however, suggest that the enemies aren’t exactly deceivers. Instead, they’re bullies who seek more literally the speaker’s neck. Is this a metaphor or a thing that happened: “baselessly they’ve | buried me a net / of a pit | they’ve baselessly | dug for my neck” (7)? What about this: “as I stumbled they joyed… attackers I did not know | they tore and did not stop” (15)? Is the perjury literal, merely figured as a scene of violent pursuit? Or are the attacks literal, the courtroom figurative? Verses 13-16 describe a personal experience of communal betrayal. “But I when they were sick | my clothes were sack,” the speaker narrates (13). “I wandered | like a mourner for a mother” (14). “But as I stumbled they joyed | and the gathered gathered against me” (15). What, exactly, happened to this speaker?

It matters who speaks. It matters because the line between vindication and vindictiveness can be fine. “Indict” and “fight” may not rhyme in Hebrew, but they are doubled and paired in the first verse. The legal system is evoked alongside the weapons of war, a nervous association. If it is read in the voice of someone bullied or abused, someone betrayed, a representative of “the weak and the poor” who seeks rescue “from who plunders them” (10), the psalm is powerfully transformative. Read, however, in the voice of an abuser, a liar, a slumlord, oil baron, or opiate magnate, some representative of those who present themselves as put upon, as victims of witch hunts, the psalm’s transformative power slips away. Because we cannot know what really happened, the speaker’s passion our only evidence, the psalm maximizes emotional availability at the expense of its resistance to being co-opted.

In the context of group recitation, therefore, Psalm 35 becomes something else. Maybe most psalms do. Without clear knowledge of the speaker’s situation, anyone can take on the role of the beleaguered. Can a majority sing this psalm, or a nation or state?

In fact, they have. The most notable example of this reading comes from Jacob Duché, Anglican priest and—until he wasn’t—American patriot. In September 1774, at the opening of the First Continental Congress, Reverend Duché read the collect of the day, Psalm 35, which John Adams described as a particularly moving experience. How could those political leaders not have identified, individually and collectively, with the desire for vindication against attackers and false witnesses? It might be hard to pin down the psalmist’s own experience—if “experience” is even singular—but the feeling of driving off enemies ran deep. Shields and spear were perfectly real. Three years later, Duché, having been jailed by the British, sent a letter to George Washington urging an end to the war, an act that led to his having to flee from America as a traitor. By the 1780s, Duché was writing to Washington again, asking for vindication against Congress, crying out for justice, feeling himself betrayed.