(of David)

* * *

With Psalm 119, this may be the book of Psalms’ most accomplished acrostic. Its basic unit is the quatrain, offset by a few tercets (dalet in 7, kaf in 20, and qof in 34), and a few longer stanzas that seem to have been expanded (nun in 25-26, samech especially in 27-29, and tav in 39-40). Across this structure, the psalm builds a multi-pronged argument against stewing over injustice. Some of its lines of reasoning are more persuasive than others, but the most developed lines emphasize an inheritance that belongs not necessarily in the future, but is already in process.

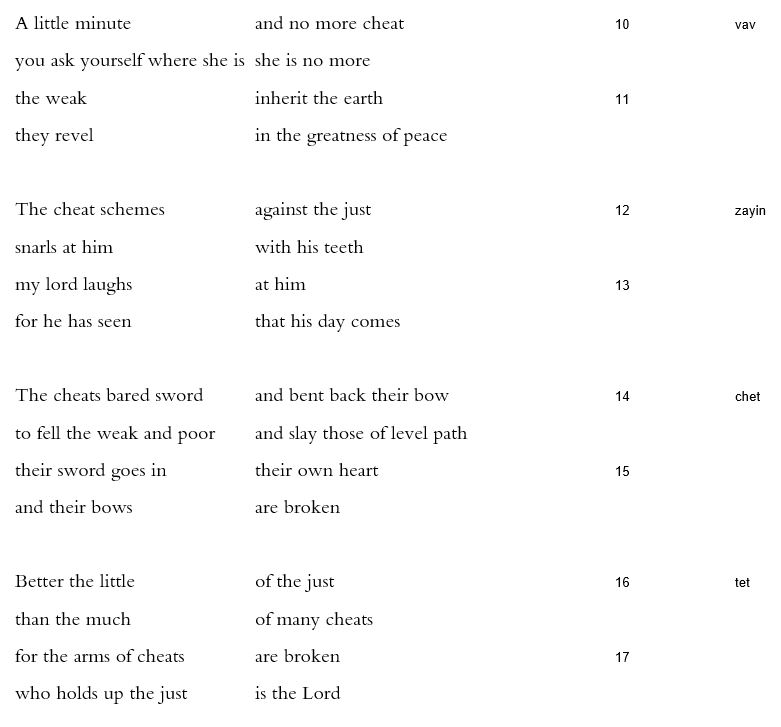

Verses 1, 7, 8 urge calm and quietism in the face of those who harm others and those who succeed. “Relax the ire | loose the rage / don’t burn yourself” (8) could be a therapist’s advice, valuable in any age of bad news. The reflexive stem of a verb for burning supports the case that the danger of outrage is what it does to the outraged. Depending on the speaker, depending on the reader, this advice also sounds just like gaslighting. One thinks of the phrase “the politics of envy,” which defends the status quo by patronizing the abused: “don’t burn yourself | over one who succeeds” (7). Similarly reflexive is the hoist-on-their-own-petard suggestion in the chet and tet verses, 14-17, that the resha`im, the villains, only injure themselves. Don’t worry about injustice, the psalm argues, for the sword and bow of the bad harm the bad themselves, and even “the arms of cheats | are broken” (17).

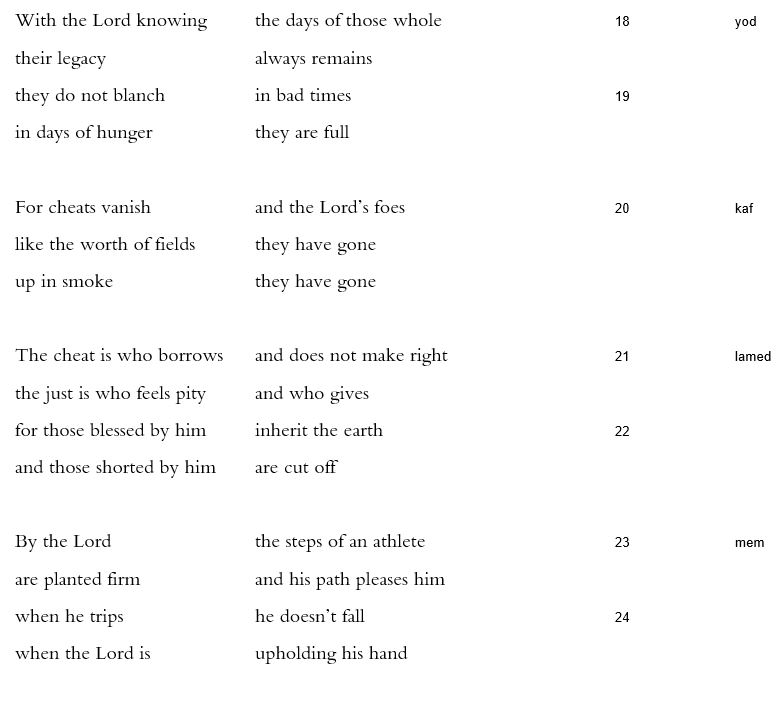

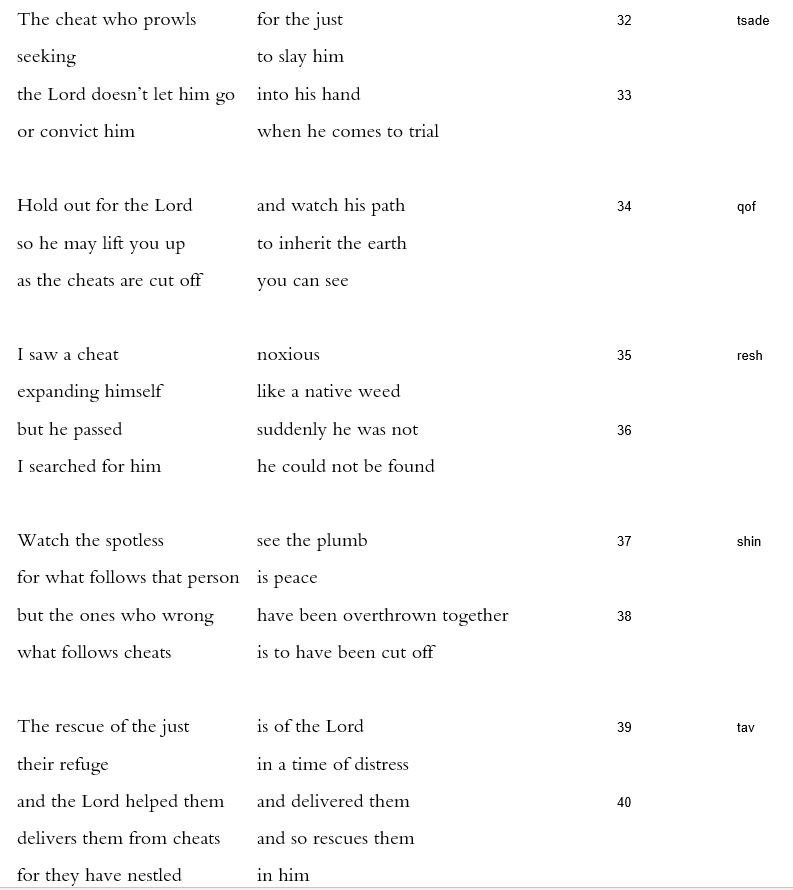

More pervasive in Psalm 37 is the repeated claim that crooks don’t last because they are cut off. “Fast as grass | they are mowed down” (2). “A little minute | and no more cheat… she is no more” (10). Their impermanence is shown in both the perfect and imperfect tenses: “his day comes” and they have gone / up in smoke | they have gone” (13, 20). “Abusers | are cut off” (9). It’s double-edged, this word “cut off,” as the same verb used to mark a covenant, the cutting of a covenant. They’re the same metaphors used for an inheritance or a deal in English: the one bequeathing can cut you in, or cut you out, cutting you off. The word shows up repeatedly, in verses 9, 22, 28, 34, 38, with “cheats” and “the offspring of cheats” and “those shorted by him” [i.e., the Lord].

What about the just, and the poor, the weak, the abused? The speaker tells them, not terribly convincingly, “I was a child | and I have grown old / and I have never seen | the just being let go” (25). “Watch the spotless | see the plumb / for what follows that person | is peace” (37). This vision is clouded at best. It calls to mind God’s chiding of Job’s so-called friends: “My rage has flared at you… for you have not spoken of me what is true” (Job 42:7). More persuasive anecdotal evidence comes in Psalm 37:35-36: “I saw a cheat | noxious / expanding himself | like a native weed.” This, by contrast, all of us have seen.

Most pervasive is the psalm’s claim, the promise, that the just “inherit the earth” (9, 11, 22, 29, 34). What this means, alas, is not exactly clear. It is associated with “reveling” in the Lord (4, 11), with a vision of things going well, the Lord “upholding his hand” (24), so that “her steps do not slip” (31). It’s associated with claims about the Lord, the Lord’s guidance, protection, rescue, and courtroom justice (mishpat accompanies tsedeqah in verses 6, 28-29, 30, and 32-33).

What’s most interesting about the inheritance of earth as presented in Psalm 37 is when it happens. So frequently, these promises are translated by the future tense—they just will inherit the earth. But the imperfect construction in Hebrew also covers the present tense, and several moments in the psalm imply that true justice, the justice that inverts the world’s many visible, upsetting injustices, is perfective as well, already accomplished, even if the waiting for the Lord continues (7, 10). The disappearance of cheats, for instance, is both seen as if prophetically— “he has seen | that his day comes” (13)— and pronounced as a fait accompli— “they have gone” (20).

Towards the end of the psalm, the blurring of past, present, and future becomes even more fascinating. The bad person whom the speaker has seen expanding himself, is described in verse 36 as evanescent: “but he passed | suddenly he was not / I searched for him | he could not be found.” Both “he passed” and “I searched for him” are in the vav-consecutive verb form, which takes the imperfect form and can be rendered by both present and future as well as by the historical present, as completed action. Similarly, the psalm’s final verse repeats “deliver” both with and without the vav-consecutive, mapping out a past and present and a future.

If the just and the weak inherit the earth now, already, our expectations shift. This is not the kind of credulous, pipe-dream hope for the future that encourages only inaction and wish-fulfillment, pie-in-the-sky. For all of its Horatian quietism— see especially verse 7— the psalm emphasizes the earth as much as it does justice. And action in the present tense is encouraged–action in the earth. “Lean on the Lord | do good / dwell in the earth | and graze on faithfulness,” verse 3 preaches, as if we ourselves have already inherited. “Swerve from bad | do good / and dwell always” (27).