(lyric, of David, to keep in mind)

* * *

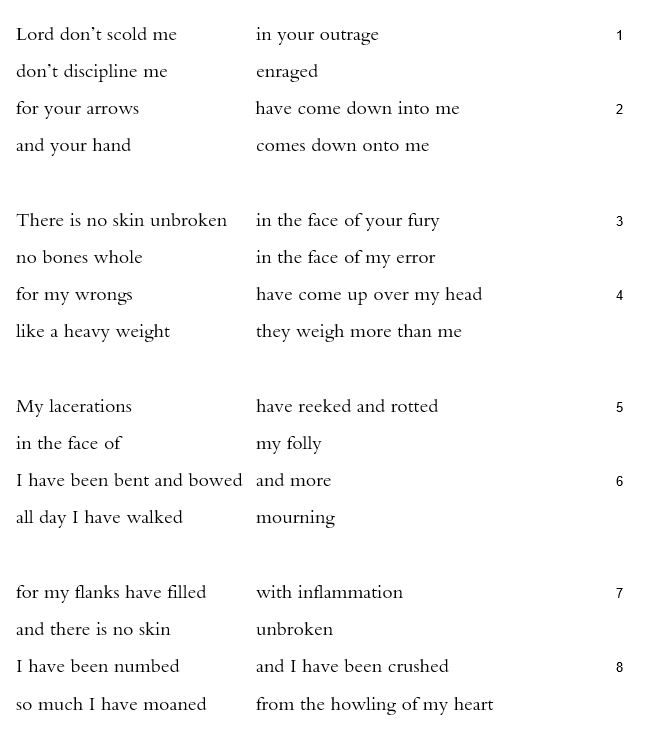

Psalm 38 is a lament as vivid in its depiction of bodily suffering as it is elusive about the causes. The speaker sees her pain first as a result of divine wrath: “your arrows | have come down into me / and your hand | comes down onto me” (2). In the second quatrain, most of the psalm’s themes arrive:

There is no skin unbroken in the face of your fury

no bones whole in the face of my error

for my wrongs have come up over my head

like a heavy weight they weigh more than me (3-4).

Paralleled, the Lord’s “fury” gives way to the speaker’s “error,” the word usually translated as “sin.” This unnamed mistake grows plural in “wrongs.” These wrongs themselves proliferate, continuing the downward movement from the punishment of the first two verses (“have come up over my head” in verse 4, see also 6 and 8) as they spread a contagion that dominates the psalm. Likewise, the repeated phrase “in the face of” recurs in the poem, both penei (3, 5) and its synonym neged (9, 17), creating an immediacy that is confrontational, face to face, even as it accentuates the speaker’s distance from her loved ones, friends, family, and God.

By far most of the psalm emphasizes the ache that spreads within, across, and beyond the sufferer’s body. “My lacerations | have reeked and rotted / in the face of | my folly” (5). But what folly? Even in verse 18, the crime she feels punished for goes unstated: “my guilt | I confess / I suffer | from my error.” Did the error cause the lacerations? When she describes how “there is no skin unbroken” (3, 7) and how “my flanks have filled | with inflammation” (7), are these injuries rather a consequence of the angry, physical “discipline” of Lord? Or are her wounds the work of those enemies who show up for the first time in verse 12: “those who seek my neck | struck me”? The outward movement of pain and its consequences reaches those who mock the speaker and beyond: “my foes are lively | they have grown strong / they have grown great” (19). These foes introduce another possibility, that the speaker’s pain comes less from divine punishment than from terrible people’s abuse: “they block me | for my chasing the good” (20). Maybe the speaker just suffers, period, certain the pervasive pain is real, and this suffering is compounded by uncertainty, and by worry about its causes as well as its effects.

The superscription indicates that this is a psalm for memorial purposes. But who is to keep what in mind? Are we supposed to agree with the sufferer’s supposition that her physical anguish stems from something she did or didn’t do, something she is or was? Are we to keep right there in mind the disappointing family and friends who distance themselves from the sufferer at the worst possible time? Or the reprobate foes who mock the sick? Or is the superscription a reminder to keep suffering itself in view, the sufferer closer to mind than anyone else in the psalm, God or family or friend or foes?