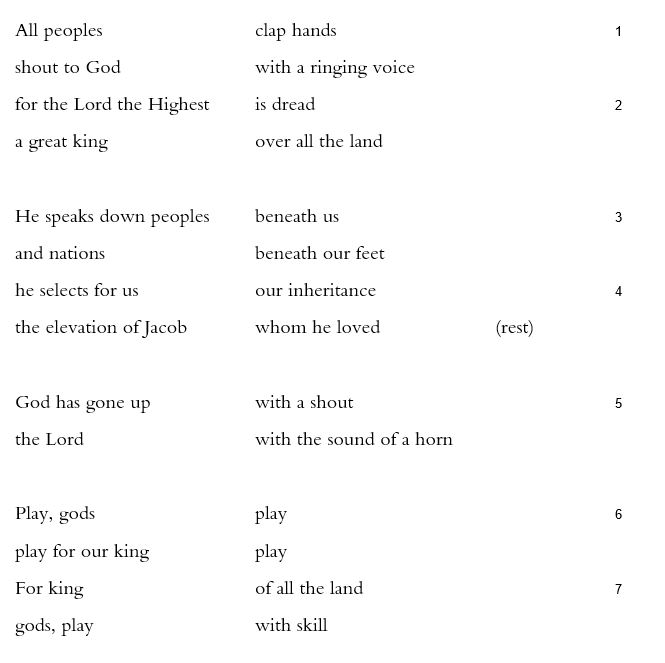

(director; lyric of the Qorachites)

* * *

There should be a name for the kinds of ambiguity that Psalm 47 presents, ambiguities impossible to preserve in translation. An overview of the psalm is simple: it celebrates the rising of the Lord, the Israelite God, as “a great king | over all the land” (2). It’s a psalm of rising. “Peoples” and “nations” are being subdued “beneath us… beneath our feet” (3) for the sake of “the elevation of Jacob” (4). Jacob’s elevation is from God’s own ascent: “God has gone up” (5), “so much | he has been lifted up” (9), “God has become king | over the others / God has been seated | on his hallowed throne” (8). The axis and ascent are perfectly clear.

Lost first in translation, however, are the ’el – `al textures that join God’s name ’Elohim with rising. “God has gone up” is `alah ’elohim (5), the verb from same root as the psalm’s final word, na`alah, “he has been lifted” (9). The verb for going up (`alah) is at the very end and the very middle of the psalm. Unsurprisingly, it’s hinted at near the beginning as well, in verse 2, both in the preposition `al (“over”) and in the epithet `elyon, which means either the highest or the Highest. English capitalization forces our hand: is “highest” an adjective describing the Lord? or an independent divinity? or an incarnation or avatar of the Lord, like Abraham’s God, El Elyon, here YHWH Elyon?

At stake is the question of where exactly God is being lifted from and where to. We assume, based on the psalms that precede and follow this one, that God’s rising reign centers in Jerusalem, though no place is stated. Is this a cosmic hymn describing an ascent to the skies, a cultic hymn describing an ark being carried up steps, a coronation hymn celebrating a king who is figured as God, or a celebration of Solomon’s Temple or the Second Temple? Ironically, this matter may be more ambiguous for us now that the psalm is in the Writings of the Hebrew Bible than it would have been whenever it was written, recited, performed, experienced. Some ambiguities are created by time and translation.

What is more ambiguous in the original, however, and impossible to capture in English because of capitalization and idiom is the meaning of `Elohim. The word can name God and take singular verbs with no confusion: “God has gone up” (5), “God has become king… God has been seated” (8). At other points, the word can be plural, referring to plural “gods” with no confusion (Ps 8:6, 82:6; Gen 35:2; Exod 22:20). And yet, in places in this psalm, `Elohim might go either way: “Play, gods | play” might be rendered “Play for God | play” (6). In verse 9, “people of the God | of Abraham” could instead be “people of the gods | of Abraham,” just as “for God’s are | the land’s shields” could be “for of the gods | the land’s shields.” These last changes would convey that, instead of these people and shields gathering to God, those people and shields are subjugated by God. Because English punctuation and capitalization signify, however, we have to decide, and none of our decisions is all that satisfying. After all, even terms like “nations” in verse 3 can be seen as references to divine or quasi-divine beings. (Dahood even has “strong ones” for the common term “peoples.”)

The exaltation of the Lord the Highest is clear, clear from the psalm and clear from the name even if we lowercase that epithet to “Lord the highest.” But it’s the psalm’s exact henotheistic or monotheistic contours that are less clear. The song seems not just tolerant of such ambiguity, but willing to revel in verbal play even with the name God. These are not flaws in the psalm. No pious rush to capitalize every utterance and every pronoun could wish away nor should wish away these traces of meanings that translations hide because they have to decide.