(director: lyric, of David, when the prophet Nathan came to him after he came to Bathsheba)

* * *

These readings of each psalm hope to peel open some of the ways each psalm means, not to pin down the only possible interpretation. Some accord better with the text and are inductively arrived at. Other readings arrive from hypotheses that precede the text. These interpretations tend to find what they go in search of. Of the two, the better goal is not to impose but to discover. At the same time, readings ought neither to aestheticize or anaesthetize or spay, but to stay alert to a lively text, to face and be faced by it. Given the thousands of years’ worth of interpreters, not to mention the continuous practice of those who pray these psalms regularly, given these traditions and lived experience, it is important not to be bullied but not to be blind.

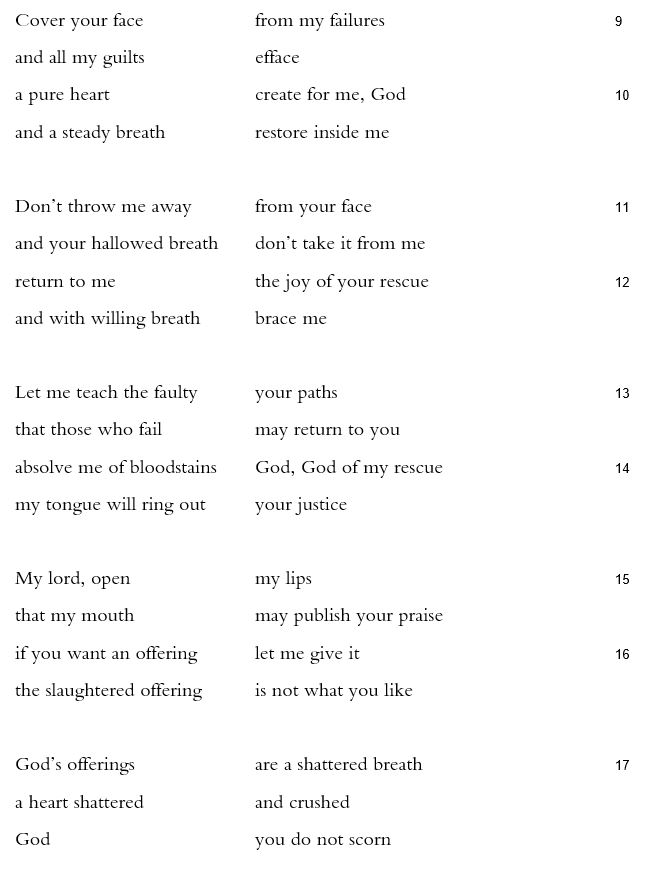

Psalm 51 challenges all of these goals. For many readers, its interiority— confessional, penitential, deeply felt, and repeatedly enacted in bodily ritual and personal devotion— combined with so many intimate imperatives (“feel for me… efface my faults/ lavishly wash me… cleanse me,” 1-2) makes it the very definition of prayer. For those readers, the rendering of chatt’a as anything but “sin” misses the point. Of the hein that begins both verse 5 and verse 6, these readers will say it must be translated as an interjection of insistence rather than as a hypothetical “if” or “whether”—not “whether with guilt | I was churned out at birth” but “indeed, with guilt| I was churned out at birth” (5).

And yet for many other readers, the sevenfold repetition of the word usually translated “sin,” plus the threefold repetition of the word “fault” and the threefold repetition of “guilt,” plus a clean/dirty binary, plus the absence of any stated evidence of criminal or ritual or moral wrongdoing: it’s just all too much. For these readers, lines like “Don’t throw me away | from your face / and your hallowed breath | don’t take it from me” (11) make this poem—and with it the Psalter and Bible and bathwater and whole ball of wax—a cringeworthy performance of groveling tantamount to psychological abuse. A line like “so that bones you crushed | may dance” buries the lede (8). What better demonstration could one want of cultural hegemony or ideological state apparatuses or Stockholm syndrome sufferers, some of these readers might say. In Psalm 50, God accuses Israel of wrongdoing. In Psalm 51, God doesn’t have to. The sheeples are busy accusing themselves.

In response, but not necessarily in defense, it’s important to preserve the little gestures of the text. The Hebrew verb for ritually taking away “failure” (techatte’eini), for instance, includes the word “failure” (chatt’a) itself, which the usual translation “purge” misses (hence the quirky “unfail me with mint”). Or take for example the word ruach for breath or spirit or wind, which appears in 10-12 and again in 17. “Spirit” is too distant and ethereal here. The scene is of the speaker’s mouth (15) and God’s face (11). Translating “Holy Spirit” in verse 11 is outright wrong. Underneath all the gestures of self-loathing is personal apology, a relational I and you. They are close enough to feel each other’s breath. The explicit “I” in verse 3 is met by the explicit “You” of line 4, in a cluster of feelings that are instantly recognizable. Lord knows I know my faults; my failures are lined here on my face. Whomever I admit this to, I am probably better off admitting than not. And it is indeed good when I am treated not for my failures and guilts and wrongs, but “out of your care / out of your many fondnesses” (1). The identifiable desire for a reset button, for “a pure heart… and a steady breath” (10), is as powerful as anything in the book of Psalms or indeed the Bible as a whole.

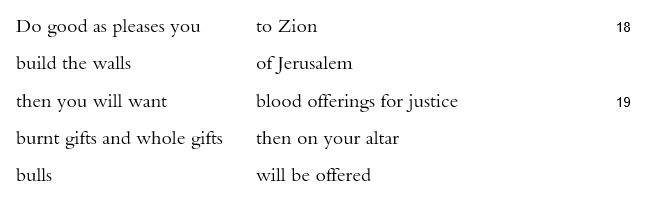

No matter how we read this psalm, one thing we can all agree on is how out of place verses 18 and 19 are. They fit nothing else in the psalm and seem almost spray-painted. They read as if at the end of Hamlet someone scrawled more lines for Horatio: “Is the rest really silence? I have some things to say about that.”