(director: with strings, instructive, of David)

* * *

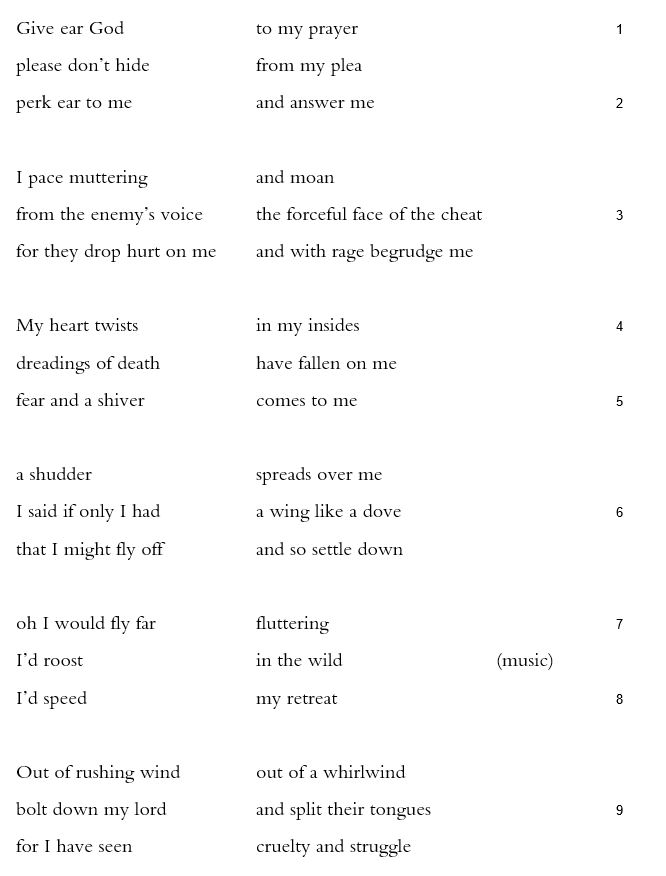

Psalm 55 appears to be deeply personal, interior, a psalmist suffering inwardly. The voice of the enemy and the face of the vile have mentally torn up the speaker: “My heart twists | in my insides” (4).

That root word for “insides,” qerev, holds the poem together. It shows up not just to describe the suffering, but the end of that suffering: “he bought back in peace | my throat in my insides” (18). Curiously, it also describes the whole city where “they” go around: “harm and trouble | in her insides / hunger in her insides” (10c-11a). They themselves, whoever they are exactly, have “bad in their lodgings | and in their insides” (15). Most intriguingly, that same consonantal root qerev shows up as qerav in verse 21 where it describes conflict within someone, someone third-person: “smoother than butter | his mouth / and aggression | was in his heart” (21). (Given that that word “aggression” is paralleled by the word petichot, which seems to mean an opened sheath or drawn sword, the similarity between qerev and cherev, “sword,” seems purposive.)

That there are numerous “insides” in the psalm suggests something less personal than it first appears. After all, the poem turns from the twisting and shivering heart (3-5) to the wish for a wing, the desire to get away (6-8a). From there it turns, hinged by “out of rushing wind | out of a whirlwind” (8b), to a second wish, a wish that the Lord would descend and punish (9). In verses 10-11 the personal becomes collective, the insides of the city. And yet just as it turns, the psalm ironically becomes more personal, the first-person speaker addressing a second-person betrayer.

For if an enemy slurs me that, I can bear

if a hater swelled against me from him I could hide

but you someone of my worth

my close friend one so known to me

who sweet talk as one in the house of God

we walk with the masses (12-14).

The piling up of appositives (“you | someone of my worth … who sweet talk as one”) deepens our sense of the speaker’s pain even though it comes no closer to naming the disloyal friend. Instead, brutally, this psalm that emphasizes insides goes all the way out into the temple with what seem like intimate whispers, only to disappear again, diffused into a crowd.

The wish for destruction that follows immediately in verse 15 still doesn’t name the “they.” Context implies the “masses” with whom the speaker and the disloyal friend walk. Their walking calls back those “in the city | days and nights / [who] go round | up on her walls” (10). Are all of them betrayers? Are they part of the city’s insides, rotten to the core, or are they invaders from without? What does “there’s no changing them | they do not revere God” (19) reveal about them? Have they—plural or singular—betrayed the speaker or have they betrayed God?

From this they whom the speaker clearly wants to see punished (the word “answer” in “may God hear | and answer at them” in verse 19 sure looks like the word “harm”), the psalm whipsaws back to the singular “he”:

He sent his hands against his friends

he broke his pact

Smoother than butter his mouth

and aggression was in his heart

his words were slicker than oil

and they were unsheathed (20-21).

Who is this “he” who sent out against his friends and broke his pact? And what is this description doing here? If this is more evidence against the disloyal friend, it seems to be justifying the call for harsh punishment. But wedged here, between calls for punishment in verses 15 and 19 (which flank a relatively straightforward call for rescue, similar to that with which the psalm began) and celebration of that punishment in verses 22-23, this third-person singular sounds almost like it refers to the one doing the punishing.

It isn’t necessary to conclude that this psalm is hopelessly broken, as others have claimed, nor that it must have resulted from two different psalms having been stitched together or interleaved. Rather, whatever the core experience of this psalm, whatever its origins, there are tensions hard to resolve. There are tensions between what happens inside and what happens outside, tensions between the singular personal experience of betrayal by one person and collective generalizations about “them, “people of blood and fraud” (23). These others didn’t break just one person’s trust, but he, the bad one, “sent his hands | against his friends” plural (20). Like Poe’s purloined letter, the insides of Psalm 55 are right there on its surfaces, inward pain facing out, suffering becoming a call for terrifyingly, problematically disproportionate response: “let death come over them | let them be buried alive / bad in their lodgings | and in their insides” (15).