(director: “The Witness Lilies,” in stone, to teach, of David, when, battling Aram of the Two Rivers and Aram Station, Joab returned to strike Edom in Salt Valley, 12,000)

* * *

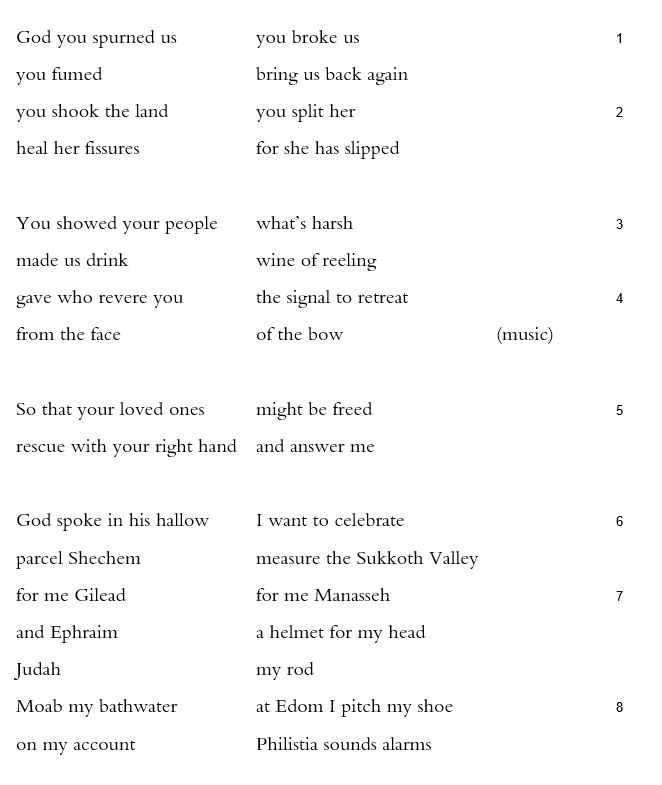

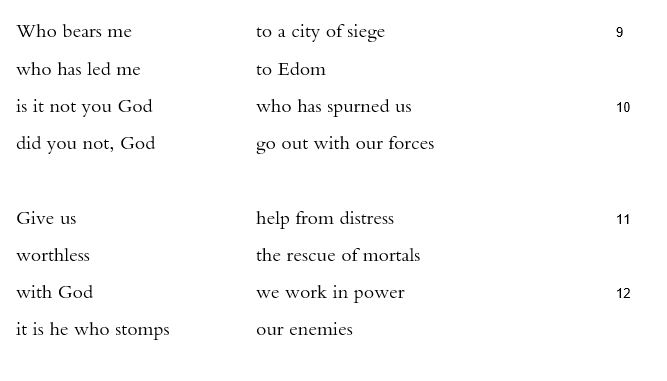

Even if biblical Hebrew had periods and quotation marks, would we want them? Our desire for clarity in poetry and song has to be weighed against the values of richness and complexity. In Psalm 60, for instance, God speaks with—or in— God’s own uniqueness, God’s sacral apartness, God’s “hallow.” God’s speech seems to begin with “I want to celebrate / parcel Shechem | measure the Sukkoth Valley” (6). It’s God who celebrates and metes out, the reader concludes, since the psalm’s previous first-person speaker is likely not positioned to apportion territory. Verses 7 and 8 also seem to be spoken by God:

for me Gilead | for me Manasseh

and Ephraim | a fort for my head

Judah | my rod

Moab my bathwater | at Edom I pitch my shoe

on my account | Philistia sounds alarms.

That shift from locations within ancient Israel and Judah to Moab, Edom, and Philistia comes with a significant change of tone, from the serious “fort” and “rod” to jokes. Moab is a “washpot.” In contemporary colloquial English, Edom gets the finger. Does this shift of tone suggest that verse 7 should have quotation marks within quotation marks, as quoted speech while verse 8 is parodic? Or is this all one layer?

It’s verse 9 that makes quotation marks seem simultaneously desirable and unwanted. Does God’s speech continue here or has it ended? “Who bears me | to a city of siege” makes sense if God or the Lord is speaking from the Ark of the Covenant. Who else besides God would be borne this way, led to Edom? Joab? A king? Because we can’t tell for certain, the questions bear both divine weight and human intimacy. Open-endedness continues—grows, even— in the question asked in verse 10: “is it not you God | who spurned us”? Surely God is not asking this of God? But then who speaks now? The speaker from verse 5? Is this speaker asking, rhetorically, “who is it who leads us to battle with Edom, God, if not you, the selfsame God who rejected us before?” Is the speaker on the battlefield trying to jog God’s memory? The negative question “is it not” gives this passage extra force. We know the answer should be “yes,” but wonder a moment all the same.

Verse 4 requires not question marks, but a period, perhaps, to clarify whether it fits better with verses 1-3 or verse 5. In continuation of the psalm’s first verses which have six verbs in the perfective form, verse 3 clearly indicates completed action: “You’ve shown your people | what’s harsh / made us drink | wine of reeling.” But verses 1-2 also have two imperative verbs: “bring us back again.. heal [the earth’s] fissures.” So does verse 5: “rescue with your right hand | and answer me.” Verse 4 is difficult, but it looks like it has an additional perfective verb: “[you] gave who revere you | the signal to retreat / from the face | of the bow.” In this reading, “the signal to retreat” parallels “what’s harsh” as “from the face | of the bow” pairs with “wine of reeling.” Without punctuation it’s impossible to decide.

Mitchell Dahood and others argue in favor of the so-called “precative perfect,” in which a perfective form takes on imperative meaning: “To those who fear you, give a banner / to which to rally against the bowmen” (75). In this reading, the speaker’s call to action starts earlier. In the grand scheme, it hardly matters. Regardless of how it’s sliced, in verses 1-5, the speaker recounts God’s prior rejections and calls for restoration, a restoration that’s wished for until the very last verse of the psalm. By that last verse, the speaker has grown all too confident: “with God | we work in power / it’s he who stomps | our enemies” (12). In a less-grand scheme, that confidence slips a little. It’s hard to tell exactly where and when in the psalm we turn from God’s prior punishments to God’s wished-for victory. And because it’s hard to tell, there’s a fair bit of quaver in that voice. Whoever says, “who leads me | to Edom” comes to sound less rhetorical and more worried.