(director: a song, a lyric)

* * *

This psalm, or “song” as it’s called by the superscription, is shaped around a series of ten plural imperatives which “all the land” is enjoined to do. Four of these insistent verbs start the first stanza:

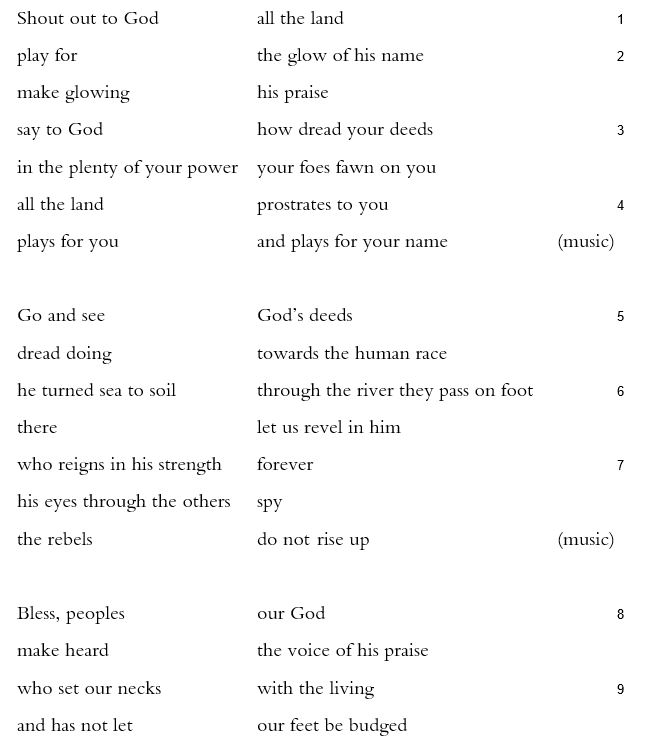

Shout out to God | all the land

play for | the glow of his name

make a glow | of his praise

say to God | how dread your deeds

These four lines neatly turn around the centerpiece of “glow of his name / make a glow,” kevod shemo simu kevod. They move from the sounds of worship to its effects.

Later imperatives carry this momentum from the effects of worship into strange maps of collective memory, taking us together away from and into the temple, then down deep into the speaker’s mouth. What begins as encouragement to make music turns into a meditation on hearing. In verse 5, the people—presumably still “all the land,” but all the “land” or all the “earth” is unclear—are encouraged to “go and see | God’s deeds / dread doing | towards the human race.” What deeds? “He turned sea to soil | through the river they pass on foot / there | let us revel in him” (6). The passage invokes scenes of creation and recreation, from the gathering of waters and appearance of dry land (Gen 1:9) to the receding of flood waters (Gen 8:8,13) to the crossing of the Reed Sea (Exod 14:21-22).

In response to this memory come the psalm’s seventh and eighth imperatives: “Bless, peoples | our God / make heard | the voice of his praise” (Ps 66:8). And yet the sequence does not culminate until verse 16, with a doubled imperative that recalls the “go and see” from verse 6:

Go and hear | that I might tally

all you who revere God | what he has done for my neck

By this point, it’s hard to know where “we” the psalm’s plural audience are and where we’re being sent. Just to recap, all across the land we have been told to make noise (1-4). We were sent back to the Exodus to see (5-7). Again we were again told to make noise (8) in praise for having been rescued by God, “who set our necks | with the living / and has not let | our feet be budged” (9). (Not budged, that is, except for this song, which whisks us all over.) In this context the next two stanzas, verses 10-12 and verses 13-15, surprise. The first of these stanzas sends us either back to the Exodus or out to exile or both: “you drove people | over our heads / we went in fire | and in water / that you might lead us out | to relief” (12). The second introduces a first-person speaker, who enters the temple to make offerings: “I come to your house | with sacrifices” (13). For a people whose feet have not been budged there’s a lot of movement.

The greatest surprise in all of this motion is where we go next, in verses 16-18. “Go and hear.” Go where? The song takes us inside the speaker’s mouth:

to him with my mouth | I called

and he was lifted | behind my tongue

if I had seen trouble | in my heart

would my lord | not hear

If this is a poem of universalism, celebrating “all the land” or “all the earth,” it is also a curiously centralizing, personalizing poem. All the history of rescue from exile, the testing of the people, all the sacrifices of the speaker, all of the tensions between feet that are not moved and the repeated commands to go—it all crystallizes inside the mouth of the speaker, “behind my tongue… in my heart” (17,18). The map of history, the acts of worship, they come together. The speaker’s ability to breathe and produce sounds allows promises “which my lips | have parted / for my mouth to speak | in my distress” (14). It also bears witness to the lifting away of distress entirely: “if I had seen trouble | in my heart / would my lord | not hear” (18).