(director: on “The Lilies,” of David)

* * *

Interpretation always risks being wrong. Vital clues might be missing or missed. Contextual signals from the primary scenes of writing and reading might be tuned too low, while noise from we the interpreters’ own culture and bent might be turned up too loud. We might not just be wrong, but pettily wrong. Take, for example, what Mitchell Dahood says of Psalm 69, calling it “the lament of an individual who prays for deliverance from his personal enemies and especially from his archenemy, Death. Kraus… rightly notes that the text of this lament is excellently preserved, but this of itself does not permit the inference that traditional translations have necessarily grasped the thought of the psalmist” (155). Who could know, ever, if we have “grasped the thought of the psalmist,” both nouns singular? Despite Dahood’s claim, this psalm has far less to do with death, let alone Death personified, than with a speaker deeply ambivalent about her own demonstrations of piety. She parades her persecutions and seeks pity, compensating for her pain with a completely disproportionate fantasy of revenge.

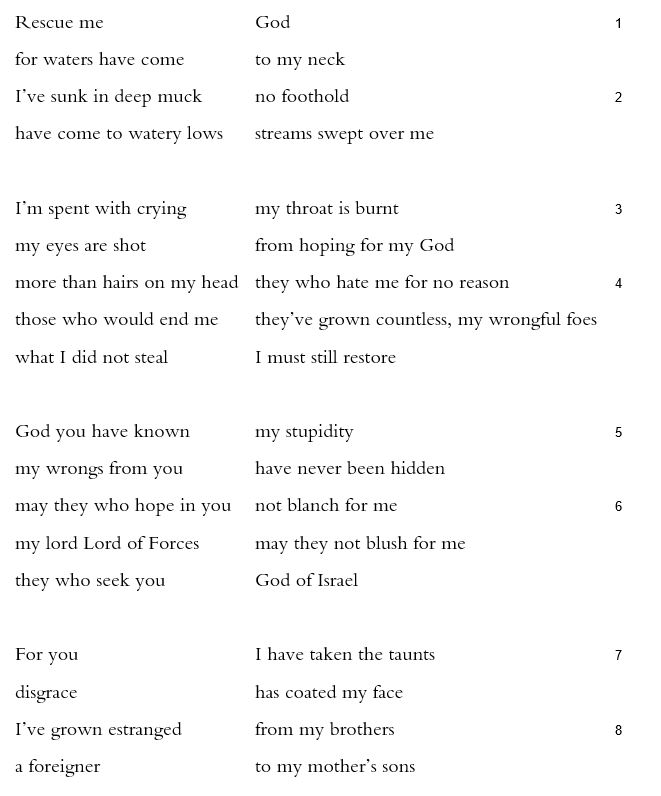

An interpretative danger more specific to psalms like this is that understanding relies so heavily on whether we believe the speaker’s claims of persecution. Our default setting, influenced by liturgical recitation and our own kind hearts, is to identify with a first-person speaker, taking as evidence of virtue her claims of virtue, ignoring the logical circle. In a society that asserts that we assume innocence until guilt is proved, a line like “what I did not steal | I must still restore” (4) easily evinces pity and fury at injustice. But reading is not a court of law. Nothing necessitates our sympathy, let alone our credulity. The first verses express that the speaker is sinking. Is this literally true or is it a topos, a commonplace? Verses 3 and 4 suggest that drowning is a figure for feeling surrounded by “they who hate me for no reason / those who would end me… my wrongful foes” (4). In these verses, innocence is asserted— “for no reason” she is hated, the foes are “wrongful,” what she did not steal she must pay back.

And yet the very next verse brings admissions of a different kind of guilt: “God you have known | my stupidity / my wrongs from you | have never been hidden” (5). If we are talking of wrongs, what exactly is the accusation, the threat, the crime? Why turn from insistence on being beleaguered to an acknowledgement of wrongs? And from there, in verse 6, why worry that the speaker’s guilt might reflect badly on “they who hope in” and “they who seek” the God of Israel?

The psychology of martyrdom deepens from there. Verses 7-12 describe the negative consequences of the speaker’s piety. “For you | I have taken the taunts… I’ve grown estranged | from my brothers… when passion for your house | devoured me / the taunts of your taunters | fell on me” (7-9). Her focus is not on devotion to the Lord, nor on anything inherent in rites such as fasting, but curiously on the opinions of others and on the “you.” The lines veer between self-pity and blaming God— “look what I have done for you… and this is the thanks I get.” In these lines, there is no real threat of death, just noise from those who mock the speaker.

Verses 13-15 return to the drowning imagery from the first two verses, with redoubled emphasis: “snatch me from the muck | let me not sink / snatch me from my haters | from the watery lows” (14). This sinking takes on added significance in verse 15, not just the wish that “streams of water | not sweep over me,” but that “the deep | not swallow me / may the pit its mouth | not shut on me.” These lines do indeed show fear of death, but death as the outcome of inundation. The deep and the pit justify the urgency behind the appeals to the Lord’s “care,” mentioned before and after the lines, in 13 and 16, alongside the threefold call to “answer me” in 13, 16, and 17. As with the earlier turn from oppression to confession in verses 4-5, this whole section of appeals to God’s care and compassion is followed by an admission: “you’ve known my scorn | my shame my indignity / right there before you | all my distresses” (19). The effect of this movement on the particularly poignant lines in verses 20-21 is to deepen whatever attitudes we readers have towards the speaker. “I hoped for pity | none / for sympathy | I found none” (20). Our own responses of pity and sympathy completely determine how we read these lines, whether we are moved to accept her figurative claims— she is literally drowning and literally dying— or retain some measure of critical distance.

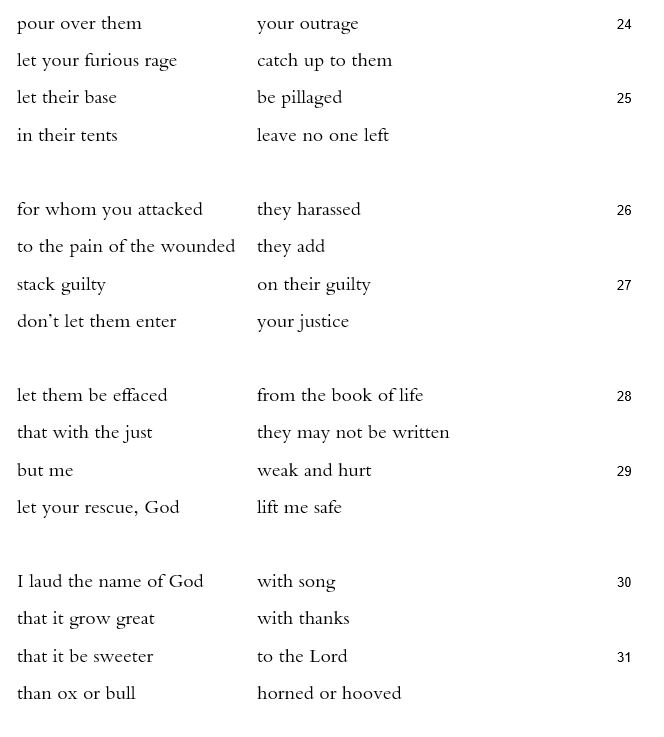

Why does our critical response matter? Because the next four four-line stanzas call for extraordinary punishment of the speaker’s enemies, a punishment that explicitly asks for justice to be withheld: “stack guilty | on their guilty / don’t let them enter | your justice” (27). There is no more mention of care or pity. Rather, she wants revenge. Not just revenge, but a storm of harm: “make their eyes | too dark to see / make their privates | constantly stumble” (23), “let their base | be pillaged / in their tents | leave no one left” (25), “let them be effaced | from the book of life / that with the just | they may not be written” (28). Lamech to his wives in Genesis 4 has not such rage.

Cumulatively, then, we have a speaker who feels beset and wronged for her convictions and practices, comparing her embarrassment to drowning. She begs rescue and sympathy, then craves revenge to the point of genocide. Sure: a danger of reading is that readings might be wrong. And so it is possible, of course, that the speaker is indeed as completely innocent as she claims. And yet a danger of sympathetic identification is how it allows us to intone with others, reciting this psalm, her terrible wish for divine justice and care to be suspended to make room for a bloodbath.

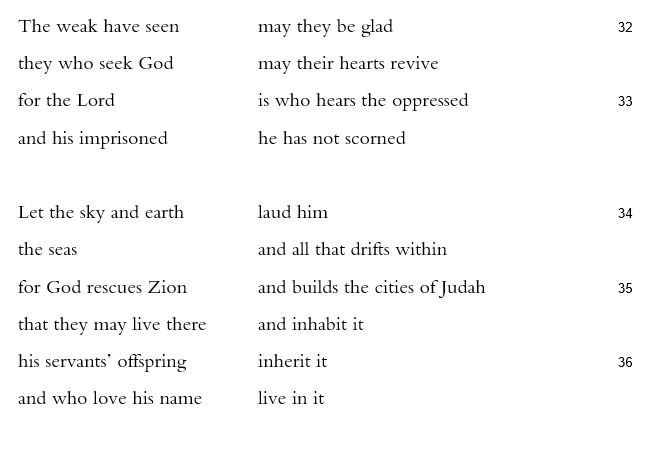

The closure of this psalm, verses 30-36, might be spoken by anyone. It makes no mention of personal circumstances, as do the previous twenty-nine verses. In this context, following the personal drama that precedes it, this part too seems like a wish. It is the moment when hot rage has passed and cool piety sets in. That hearts might revive, that the oppressed might be heard, the imprisoned rescued, the whole earth rejoice—these all are sentiments worthy of praise. But reading the psalm, actually reading it, demands that we ask how these final verses—the rescue of Zion—fit with what comes before. Again, our answer depends on the dynamics of identification. How willing are we to indulge the fantasies of the speaker in verses 22-29?