(director: don’t destroy, an Asaph lyric, a song)

* * *

Repetitive lines go nowhere fast but are easily explained. “We give thanks to you God | we give thanks” (1) and “don’t raise your horn / don’t raise high | your horn” (4-5), for example, pose only the question of why one should say the same thing twice. (For casual readers, “say the same thing twice” could be a tagline for the entire book of Psalms.) Similarly easy to explain are simple parallels (“not from the east | not from the west / not from the south,” 6) and perpendiculars (“this one he lowers | and this one he raises” 7; “all the horns of cheats | I cut off / and the horns of the just | are raised” 10).

Lines that leap, however, cover much more ground, at the cost of losing readers along the way. Psalm 75 has several such leaps. What the second half of verse 1 means, for instance, is puzzling on its own, but even more challenging is what the verse’s half-lines have to do with each other or with the rest of the psalm. How exactly do we get from thanks and thanks to nearness to marvels? Then, from this gratitude and closeness and marvels, how do we get to God’s speech about judgment in the verses that follow? How do we get from there to the cup of wine in verse 8, and from there to the first-person singular speaker, not God, in verse 9, back to God in verse 10?

Liturgical-minded readers argue that this psalm must have been part of a rite, its dialogical features literally recited by different speakers and groups. Its continuities do seem choral, its discontinuities a feature of the form in practice— a church bulletin with some lines in bold for the robed to say. These claims seem all at once persuasive and yet entirely unfalsifiable and not terribly helpful besides. Regardless of who speaks when, logics apply. The choir— the “we” who may not speak again after verse 1 (unless verses 6-8 are pronounced by them?)— is thankful. Its thankfulness seems either a cause or as an effect of “your near name” which “your marvels recount.” But is God’s response a response to the gratitude? Is it a reply to the invocation of God’s name? Or is it an example of some of the marvels to be recounted?

Verses 2 through 5 are readily understood. In verses 2-3, God declares that justice is God’s own, God’s to decide, and that it is the result of a vertical order imposed on a fluid cosmos. That vertical order of creation, verses 4-5 add, is a social order as well. The bad should know their place and keep from lifting their “horns,” an overdetermined image of noise, masculinity, abundance, and power. Verses 6 and 7 follow multiple lines of association: a move to include the horizontal (“east…west… south”) before returning to the vertical, a repetition of the keyword “raising,” a return to the naming of God as judge, now in the third person (“Oh God | is who decides”).

Verse 8 might be the psalm’s farthest leap. From horns and compass directions, from the vertical axis of raising and lowering, the poem turns to a cup. It turns confidently, in short syllables ki kos beyad Yahweh, with that conjunction ki that can express, among other things, causality (“for” or “because”) or asseveration (“oh” or “indeed”). Like the horn, the cup is overdetermined, conveying abundance, participation, determinism. Because of this multivalence— all the dreamwork of condensation, displacement, and secondary revision— both terms become prominent symbols in apocalyptic literature (cf. Isa. 51:17-22, Ezek 23:31-33; Dan 8; Rev 13:1, 14:10). Here in Psalm 75, the cup serves as a focal image for God’s deciding, the means by which the lowering and possibly the raising happens (“doubtless its dregs / they drain and drink, | all the cheats of earth” (8). The details of the wine itself are unclear —is it red? foaming? churning or churned?— but they call back the chaotic liquidity from verse 3. The wine’s dregs figure both the depths of God’s intentions and the deep greed of the bad.

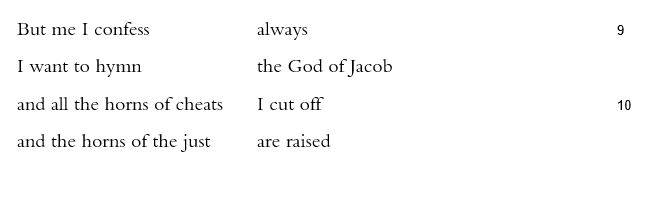

All that would seem left for the psalm is for the speaker to express the obvious, that this hymn stands against such cheats, and knows its place (9). But it still has one more turn. God, who has spoken and been spoken about, who has held and poured his cup of wine, speaks once more, also stating the obvious, that “all the horns of cheats | I cut off / and the horns of the just | are raised” (10). These last two verses are linked by a pun that makes their call and response seem linguistically inevitable. “I confess,” the speaker says, ’aggid. ’Aggade`a, God responds, “I cut off.”

As always, moments like these need to be taken with a dram of historicism. Too much historicism makes psalms relics. Too little releases their images to the reins of the worst eisegetes, who hunt their own hatreds to help them make sense of literal horns and cups. The cutting off of horns, besides being an image of taming and emasculation, is linked by both verb and noun with the destruction of altars, which is the subject of Psalm 74 as well. Despite its apocalyptic rereadings, in other words, Psalm 75’s punishment of those who raise their horns too high is not really about the end of times. It makes much more sense as a curiously assembled historical celebration of the destruction of the altars in the northern kingdom of Israel, held together beyond its moment by praising God’s power to raise and by admonishing the people not to stick their necks out or up.