(director: strings, an Asaph lyric, a song)

* * *

Once we admit that the selah notations in Psalms do not necessarily mark section breaks, as here in verses 3 and 9 of Psalm 76 (cf. Pss 4, 20, 46, 52, 55), it’s possible to see different structures. The twenty-four lines of this psalm yield either four six-line stanzas or six four-line stanzas (assuming that the word ’eshtolelu, “they were pillaged,” in the now-abbreviated verse 4 was sent off to verse 5, which was already long). All such decisions about stanzas are interpretative, clearly, but valuable for the parsing of the psalm or “song.” And while all such decisions might be misleading or wrongheaded, it is impossible to escape shaping the words on the page. What justifies the four-line stanzas in this translation? They make marginally more sense of the two thorniest passages in Psalm 76.

As with the Asaph psalms that immediately precede it, Psalm 76 works through scenes of ruin and explanatory theories of divine distance and ire. To “a waste in an instant/ done | wiped out with disasters” (73:9) and “what’s been ruined so long/ all that the enemy harmed | in the sanctuary” (74:3) and the cup of wine that “all the cheats of earth” drink dry (75:8), Psalm 76 adds more. Now there are battle scenes in Zion— “there he smashed | the archers’ fire / shield and sword | and war” (3)—and aftermath—“none of the men of force | could find their hands / out of your punishment | God of Jacob” (5-6)—and divine rage—“You | dread you / who could stand in your face | in your moment of wrath” (7).

The second half of the psalm is dominated by “dread,” framed by two uses of the participial adjective nor’a, first wedged between appellative pronouns in verse 7, then wedged in verse 12 between “princes” and “kings.” In different forms, dread appears in verses 8 (yar’ah) and 11 (lammor’a) as well. The nor’a form in particular is part of a sound cluster that organizes the whole psalm, from nod’a (“known,” 1) to na’or (“bright-lit,” 4) to nirdam (“knocked cold,” 6) to nidaru (“Make vows,” 11). Dread, repeated most often, thus links God, known and shining and feared, with three different human responses: fear, paralysis, and commitment.

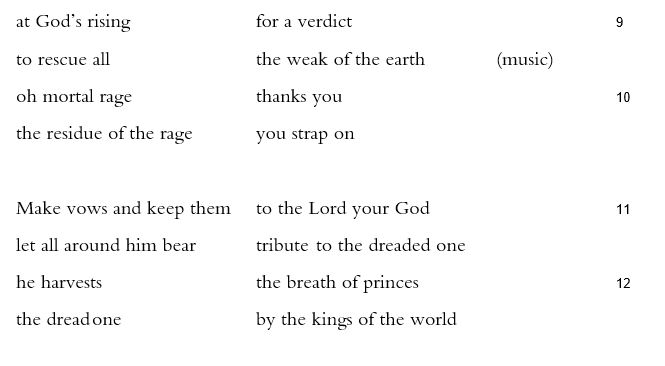

Seeing the psalm as six quatrains shows each half as having three sections. In the song’s second half, God’s wrath (7-8) is followed by God’s rising to judge and govern (9-10), followed in turn by the obligations of insiders— “Make vows and keep them”— and outsiders— “let all around him bear |tribute to the dreaded one / he harvests | the breath of princes” (11-12). The otherwise inexplicable verse 10, separated from verse 9 by the selah, is now part of God’s rising “to rescue all | the weak of the earth.” Mortal rage becomes thanks and praise. And with what is left of that rage, according to the strange figure of the psalm, God makes a belt. Read this way, outrage turns into gratitude, while its remainder becomes a garment of justice. May midrashim and therapists have ears to hear.

Similarly, in the first half of the psalm, three four-line stanzas can be seen. The first locates— nearly relocates— God in Zion, relating Judah and Israel in a gesture as likely to be a parallel as it is a tension between the northern and southern realms (1-2). The second stanza recollects battle (3-5a), while the third concentrates on a kind of slow-motion inability of warriors to respond (5b-6). The real puzzle, which neither a four-line nor a six-line structure completely resolves, is what to do with verse 4 and the first part of verse 5:

bright-lit, you | and lofty

out of mountains of prey | they were pillaged

Finding sense, however, is not impossible. God routed warriors, according to verse 3. Verse 4 turns the camera to God in a shift to the second person, where the “you” is lodged between two modifiers “bright-lit” and “lofty.” Mention of the mountains recreates the divine relocation to Jerusalem (at the Davidic centralization of the monarchy, and/or after the Babylonian exile) even as it characterizes God in battle gear as an apex predator. “They were pillaged” completes this stanza of description by looking forward to the next stanza of the warriors’ incapacity. “They were pillaged” looks back to the archers and ahead to “the valiant of heart.”