(an Asaph lyric)

* * *

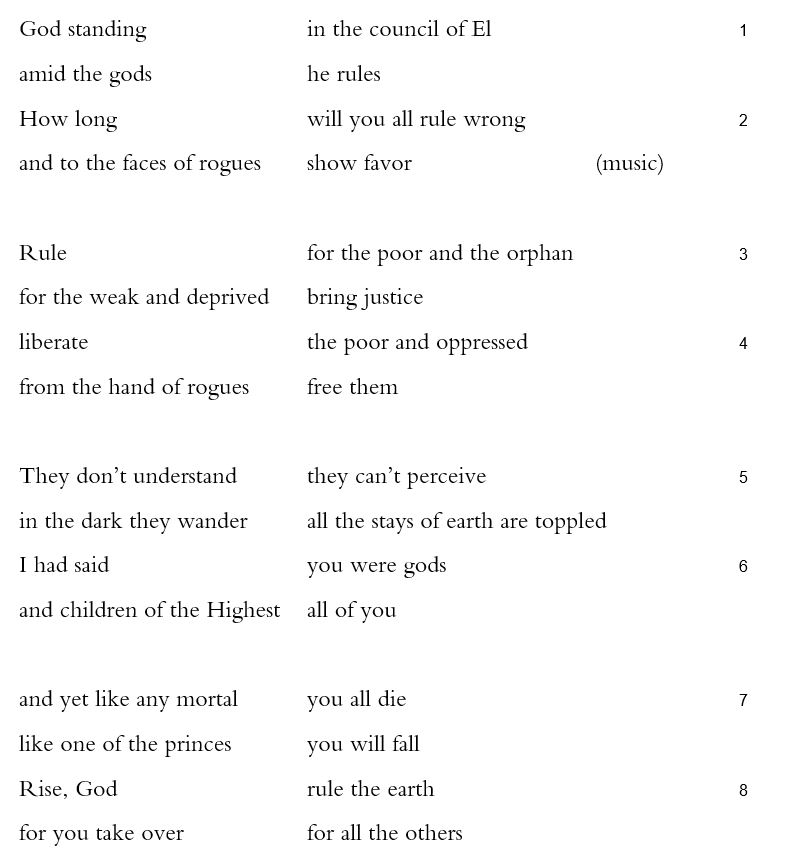

Psalm 82 is the best example in Psalms of the value of cherishing ambiguity, not just tolerating it. Where does God (’elohim) stop and the gods (’elohim) begin? There are no quotation marks here, no attributive tags to delimit who speaks when. So is it God who speaks in verses 2-7, or in verses 2-5, or 2-4, or just verse 2, or not at all? Are “they” who “don’t understand” in verse 5 the “gods” from verse 2 or the “rogues” from verses 2 and 4, or both? To what extent are the gods, all of them, just a device, a projection that looses the powerful moral of the psalm— indeed, of the Bible as a whole— those quadrupled plural imperatives of verses 3 and 4?

Rule | for the poor and the orphan

for the weak and deprived | bring justice

liberate | the poor and oppressed

from the hand of rogues | free them.

We have options. It could well be God (’elohim) who stands and admonishes the gods (’elohim) in the council of God (’el), wearily wondering when these pretenders will stop providing cover for scoundrels. But the psalm works equally well if the speaker of verse 2 is the psalmist as well, “How long | will you all rule wrong.” It’s the psalmist, ultimately, who wants the gods— and God— to bring justice to the poor. And yet the psalm also imagines that it’s God who wants this justice to come from the gods, among whom God stands. Because the imperatives are plural, everyone who recites the psalm repeats the commands to everyone around. Rule for the margins, bring justice, liberate, free. Later, whoever speaks in verses 6 and 7 presents the realization that, having said “you were gods / and children of the Highest | all of you” there is still an “and yet….” This realization is both God’s denunciation of other gods, God’s rising over them, and the psalmist’s demotion of the entire divine council.

The witty turn in verse 5 at the psalm’s center is especially ambiguous. “They don’t understand | they can’t perceive / in the dark they wander | all the stays of earth are toppled” blends ambiguous pronoun reference with squinting modification. Both of these traits, in ordinary referential prose, are grammatical errors to be avoided. Who are “they”? Proximity to an antecedent implies the human “rogues,” resha`im being the most recent plural noun (4). But “they” makes at least even more sense as “the gods” from verse 1, the gods who were charged with the four plural imperatives enjoining justice and freedom. Thus the cheaters and the gods are indistinguishable for us in their idiocy. Neither group can “perceive,” let alone “perceive / in the dark,” for both groups “in the dark wander.” Darkness works both ways. And so both groups “are toppled,” the word that comes next in Hebrew, before we learn that it is the very foundations of the world that are being shaken, shaken in a moment of comic genius, by the bumbling of blind, rogue gods. The foundations of mythology itself are toppled by gods like the crashing wooden sets of Keystone Cops.

It’s a remarkable moment in a remarkable psalm, both comedic (it is tempting to render “council” in verse 1 as “boardroom”) and earnest, both antiestablishment and authorizing of power: “Rise, God | rule the earth / for you take over | for the all the others” (8). Its layers really make it, thematically as well as narratively. That a human psalmist should command God to take charge, displacing gods who are displaceable as any human authority, is probably the psalm’s finest doubled meaning. It’s also a tremendous setup for Psalm 83, the final Asaph psalm.