* * *

In its syntax, Psalm 99 is rough going. Commentaries have called it “extraordinarily agitated.” At least at its start, finding its seams is frankly a bear. From the second verse, some half-lines seem like interruptions, pious asides, or call-and-response.

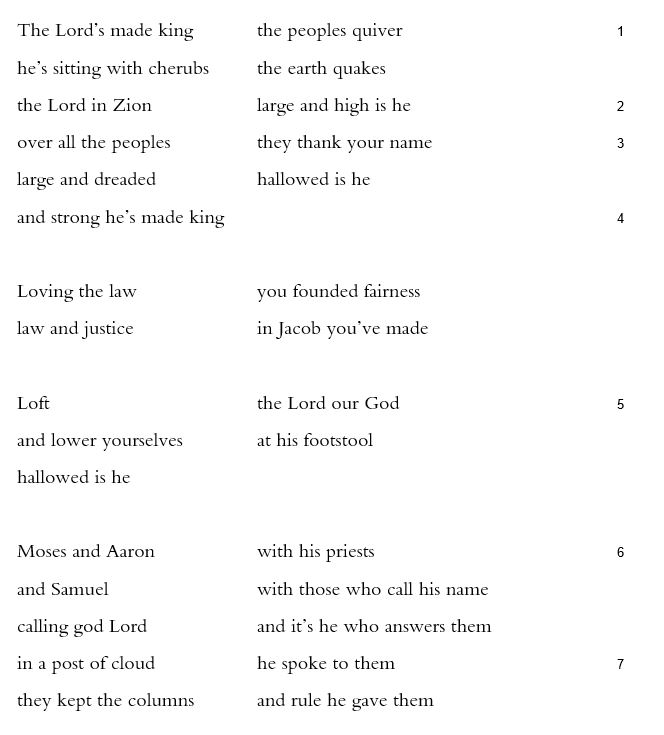

The Lord’s made king | the peoples quiver

he’s sitting with cherubs | the earth quakes

the Lord in Zion | large and high is he

over all the peoples | they thank your name

large and dreaded | hallowed is he

and strong he’s made king (1-4a).

The first two lines are no challenge. The Lord’s crowning is causal, twice. It affects the human and the wider world. Even the next half-line is clear: “the Lord in Zion” adds a third parallel to the Lord’s position. But adjectives, pronouns, and prepositions follow, with overlapping possible predicates: “the Lord in Zion is large and he is high over all the peoples” or “the Lord in Zion is large and high, he above all the peoples” or “the Lord in Zion—large and high is he—is over all the peoples.” What pairs with what gets blurred. How does “they thank your name” fit? Is the Lord’s name “large and dreaded”? It may be polysemous, but it’s also choppy waters.

Nevertheless, there are ample cues that pattern the psalm as a whole. There’s a graceful kind of three-against-two polyrhythm supplied by a pair of refrains. Like Isaiah’s vision of the divine throne, Psalm 99 features a threefold incantation that celebrates sanctity and sacralization: “hallowed is he,” verses 3 and 5 intone, and verse 9 echoes, “hallowed is | the Lord our God.” (There’s a fourth “hallowed” in verse 9, but it’s grammatically and orthographically distinct.) The psalm also falls roughly in half, each section building to the contrastive lines “Loft | the Lord our God/ lower yourselves” (5, 9).

Once we notice the halves, it’s easier to see that each half steps through three perspectives: third-person narrative (1-4a, 6-7), then second-person singular address to the Lord (4b-c, 8), then second-person plural imperatives to the assembly (5, 9). Into this structure are set like gems seven mentions of the Lord’s name (1, 2, 5, 6, 8, 9 x2), four instances of the word “God” (5, 8, 9 x2), three of the word “you” (4 x2, 8), plus four of the word “he” (2, 3, 5, 6). (It’s worth pointing out that while the pronoun hu’ sounds insistently masculine in English, it’s not gendered in biblical Hebrew. Not that biblical diction about God overall is less predominantly male or masculinist in other pronouns or parts of speech or in the broader ancient cultural imagination, just that readers and reciters should do with hu’ —and the imagination—as they will.) Overall architecture clearly matters more important to psalmist and editor than does mere clarity.

What’s suggested by this architecture is that the second half of the psalm is a completion or analogue of the first. There is a progressive logic from the third to the second person, from the Lord to the people, from “you” to “you all.” The Lord being enthroned (1-4a), the psalm argues, priestly infrastructure follows (6-7). The law having been founded on the principle of fairness—and depending on how we read verse 4a, on “strength” (4)— the now-priestly institution of remitting sins follows (“who lifts away,” 8). In this way, the psalm enacts the process of making sacred. It grounds in narrative and divinely sanctions the climactic worship gestures of raising and lowering, getting the people not just to “extol” but to actively raise “the Lord our God” while physically prostrating themselves in worship (5, 9).

The crucial reason for translating qadosh as “hallowed” rather than “holy” is that holiness implies some numinous essence, some essential trait or plane of existence. Hallowing, by contrast, is a process: historical, liturgical, and in the case of Psalm 99, textual. To acknowledge this difference is not to empty the term “hallowed” of significance. One can still see the process of sacralization as a kind of growing awareness or attunement, even as a wiping clean of the windows of perception. But hallowing is part of the very human act of making meaning, a process one must always historicize.