* * *

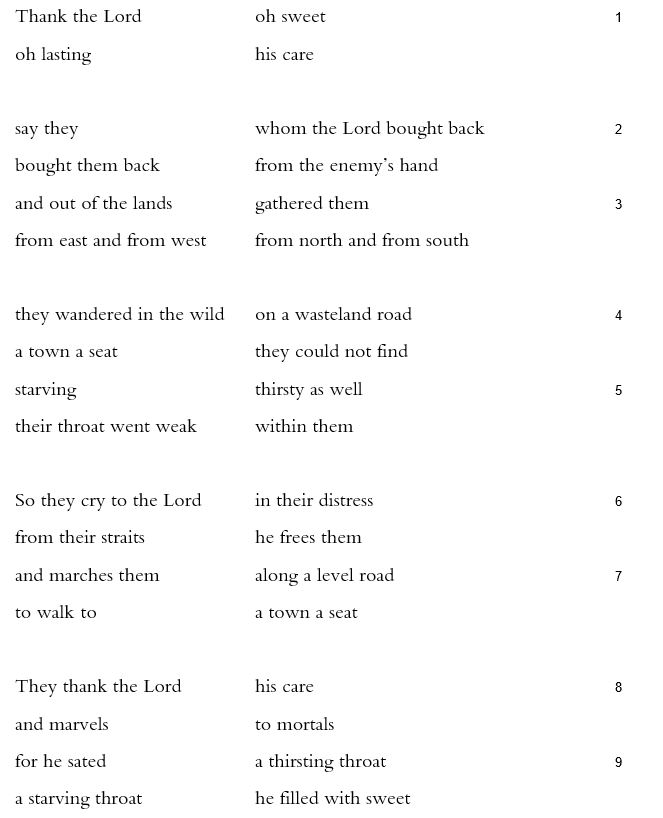

The fifth collection in the book of Psalms begins with the ambitious Psalm 107, whose quadrupled double refrain marks out two pairs of large-scale parallels. The psalm’s adroit wordplay deepens its thematic point: that the Lord’s care (1, 42-43) leaves hints everywhere, even down to the semantic dismantling of the key clause from verse 4, `ir moshav lo’ matsa’u, “a town a seat | they could not find.”

The first refrain (call it A) appears in verses 6, 13, 19, and 28, with subtle variations: “So they cry to the Lord | in their distress / from their straits | he frees them” (6). In verses 13 and 19, vayyitsa`aqu becomes vayyiza`aqu, a variant as close in meaning as it is in pronunciation: “cry” vs. “cry out.” In the same verses, “he frees them” becomes “he saves them,” which in verse 28 becomes “he leads them.” In all four verses, the chiastic shape follows the inverse operation of rescue: they cry from trouble, from troubles (a plural, more precise word) they are released. The second refrain (B), in the identical verses 8, 15, 21, and 31, has only one predicate: “they thank the Lord | [for] his care / and marvels | to mortals.” The logic of these A + B refrains could not be simpler: they cry out, he helps, they give thanks. Given their forms, those verbs can be understood differently, stretching the timeframe but keeping the causal chain: they cried out, he helps, let them give thanks.

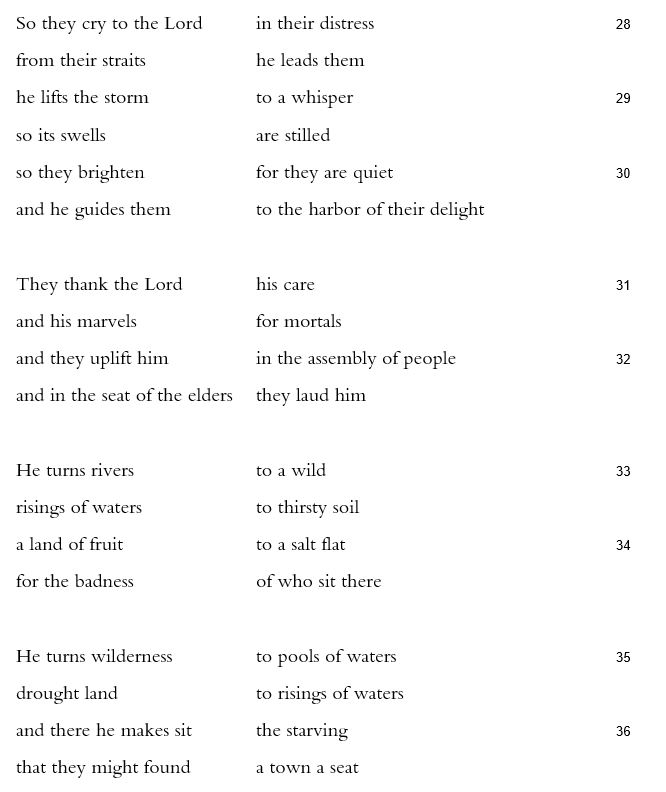

Before each A refrain is a variable-length section (call it X) describing a predicament that faces “them,” the “they | whom the Lord bought back… and out of the lands | gathered them” (2a-3a). The four cardinal directions from which the people have been gathered (3b) may align with each of the four quandaries: those lost in the wilderness, whose “throat went weak | within them” (5b); those “prisoners of want | and iron,” whose throats are presumably chained (10b); those who “oppress themselves / all food | their throat detests” (17b-18a); and those storm-tossed mariners whose “throat | goes badly queasy” (26b). After each refrain is, with one exception, a single, additional, nonrepeating verse (Y): in other words, an A + Y || B + Z pattern. The Y verses, those between the A and B refrains, make the rescue specific for each situation: for the lost, the Lord “marches them | along a level road” (7a); for prisoners, the Lord “leads them from the dark | and deathshade” (14a); and those who harm themselves, “he sends his word | and heals them / and delivers them | from their depressions” (20). The rescue is doubled for “they who go down to the sea | in ships” (23):

he lifts the storm | to a whisper

so its swells | are stilled

so they brighten | for they are quiet

and he guides them | to the harbor of their delight (29-30)

Similarly, the verses that follow the B refrain detail each group’s gratitude. Both of the first two verses name a pair of reasons to be thankful: “he sated |a thirsting throat / a starving throat | he filled with sweet” (9a); “he shattered | doors of bronze / and bars of iron | he severed ” (16a). The last two both name a pair of ways to be thankful: “and they offer | offerings of thanks/ and tally his works | with shouting” (22); “and they uplift him | in the assembly of people / and in the seat of the elders | they laud him” (32). Altogether the fourfold repetition of this x + A + y + B + z functions just like parallelism on the smaller scale of a single verse or two: theme and variations, difference within similarity, what Coleridge calls “shapeliness,” “when the whole and the parts are seen at once, as mutually producing and explaining each other, as unity in multeity.”

Through this edifice run two sets of word clusters, one playing on the word moshav, a seat, a place to dwell, the other twisting the word matsa’, finding. The prominent A refrain, for example, features the letter tsade, repeated in the crucial words “cry,” “distress,” “straits,” and “frees.” More obvious examples include the clauses and phrases umei’aratsot qibbetsam, “and out of the lands | he gathered them” (3), va`atsat `elyon na’atsu, “and spurned | the plan of the Highest” (11), yotsi’em mechoshekh vetsalmavet, “leads them from the dark | and deathshade” (14), and the opposed lines umotsa’ei mayim ltsimma’om, “risings of waters | to thirsty soil” (33) and ve’erets tsiyyah lemotsa’ei mayim, “drought land | to risings of waters” (35) the words “thirsty,” tsemei’im (5, 9) “deathshade,” tsalmavet (10, 14), “in the deep,” bimtsulah (24), and “binding,” me`otser (39). Together, this sprawling cluster emphasizes not just threats like thirst and binding and shadows and the deep, but also finding (matsa) and leading out (yatsa), crucial to the theme of rescue and return.

The smaller cluster is even more cohesive, consisting entirely of various forms of the root word yashav, to sit or dwell. The people who could not find a seat (moshav, 4) are led towards a seat (7). The second group of people rescued are “those sitting” (yoshbei) “in the dark | and deathshade” (10). After the final group of people is rescued and the people thank the Lord, the final act of gratitude is praise from the elders from their seat (ubemoshav, 32). The sequence culminates with verses 34 and 36, with the contrast between those who dwell (yoshbei) in the desert waste and their opposite, those the Lord “makes sit” (vayyoshev) in the fruitful land, “that they might found | a town a seat” (moshav, 36). The seat is not just found, but founded.

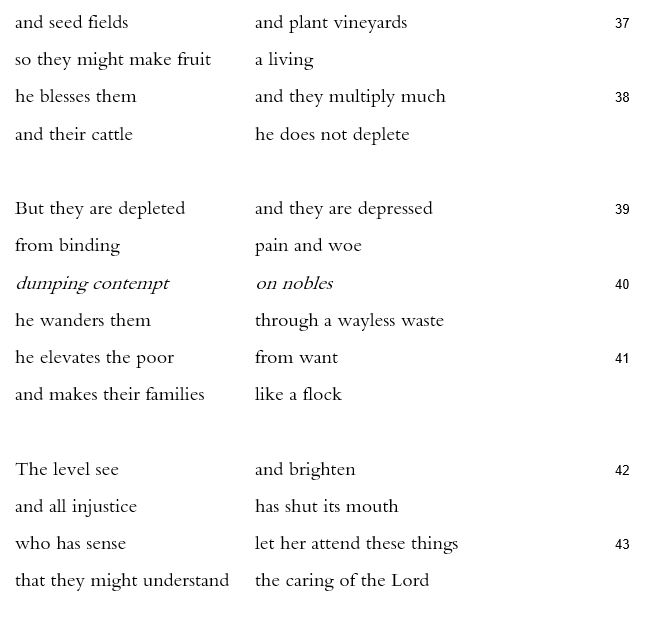

The psalm’s coda is elliptical, dialogical, and profound. While verses 33-36 evenly oppose thirst with fertility, verses 37-38 extend that fertility to a vision of a flourishing society: “he blesses them | and they multiply much / and their cattle | he does not deplete” (38). For their part, verses 39-41 portray a new situation that feels similar to the first group’s troubles, showing that rescue is not yet complete:

But they are depleted | and they are depressed

from binding | pain and woe

dumping contempt | on nobles

he wanders them | through a wayless waste

he elevates the poor | from want

and makes their families | like a flock (39-41).

This wandering like a flock shows a work in progress. The poor may be lifted up, but the people here do not yet seem to have “a city a seat.” Still, if we have paid attention, the pattern is clear. Trouble, cry, rescue, thanks.

This psalm’s interest in history differs entirely from the two psalms that precede it. It extends care and rescue, rather than limiting them. The difference signals the direction of the final collection of the book of Psalms, which explores the meanings of chesed, sweet and lasting care.