* * *

The first stanza of Psalm 114 is quoted in a famous letter to Dante’s patron Cangrande della Scala, as the author (who may not be Dante) justifies the Commedia as a “polysemous work,” one that means both literally and allegorically:

“if we look at the letter alone what is signified to us is the departure of the sons of Israel from Egypt during the time of Moses; if at the allegory, what is signified to us is our redemption through Christ; if at the moral sense, what is signified to us is the conversion of the soul from the sorrow and misery of sin to the state of grace; if at the anagogical, what is signified to us is the departure of the sanctified soul from bondage to the corruption of this world into the freedom of eternal glory.”

Twenty-first-century readers of Psalm 114 are unlikely to share these exact modes of interpretation. Some may schematize interpretation differently, following the medieval system of pardes, for example (peshat—the plain sense, the surface; remez—the hinted, a sense below; derash—the sought-for senses of midrash; sod—the sense concealed), or guiding thought by the meticulous methods of specialist scholars. Still, everyone agrees: there’s more to this psalm than meets the eye.

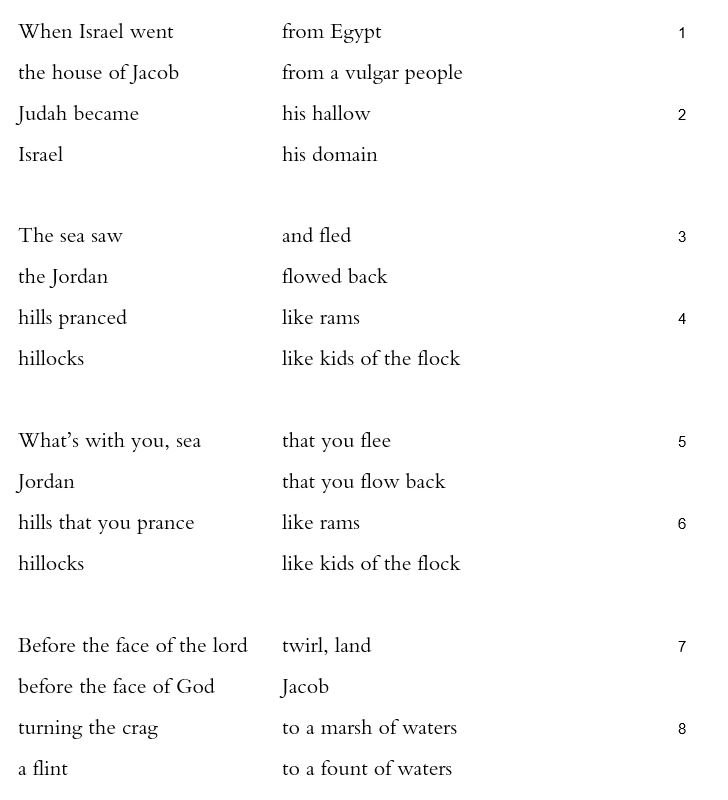

Even on its literal levels, “what is signified to us” proliferates and puzzles. It’s a psalm of pairs and parallels, to an unusual degree. Everything has a partner, from Israel and Jacob in verse 1, Judah and Israel in verse 2, Israel-Jacob and Judah-Israel in that first stanza, to the doubled triples crag-marsh-waters / flint-fount-waters of the final verse. The middle two stanzas track just about point for point, with three verbs and all seven nouns reiterated, the key difference being that the third stanza interrogates what the second stanza describes. If literal means historical, the going-out that the psalm commemorates is not just the “departure… during the time of Moses,” but the crossing of the Jordan after Moses’ death (Joshua 3). Both “literal” and “historical” also indicate when the psalm was sung and written, which clearly, according to the psalm’s first words, must have been later than those events of legend but is otherwise impossible to pin down. Why, when, and for whom does the psalm memorialize the heaping of waters at the Reed Sea and at the Jordan? Why wonder in that third stanza, unless to show wonder? And why command the earth to writhe? Is the point to see Moses’ act of striking the rock not as a pretext for preventing his entry, but as providence, the watering of a rocky land?

These questions do not arise with allegory. They come from reading the letter. They all root in the literal—why one Judah inside two Israels plus a Jacob (two Jacobs if we count verse 7); why, though Judah is “his hallow,” is Israel merely “his domain”? And yet, rooted in the literal, the questions stem and bloom elsewhere.

In other words, this is not a psalm interested in “redemption through Christ” or “the conversion of the soul” or the 613 commandments or the Ein Sof. What it does is to invite reciters to see the land between the Jordan and the sea as a mythic site of restoration. Like Genesis 1— which also begins with a b– preposition attached to an infinitive construct (bets’eit Ps 114:1; bere’shit Gen 1:1) and which also features the verb hayetah in its second verse (“and the earth was | empty and void” Gen 1:2; “Judah became his hallow”)— Psalm 114 is a creation story. Reversing Genesis 1, Psalm 114 begins with dominion (“Israel | his domain,” mameshlotav, Ps 114:2; cf. limemshelet, “to rule the day… to rule the night,” Gen 1:16, velimshol “to rule day and night”) and ends with waters and waters (cf. mayim lamayim, “the waters from the waters” Gen 1:6). Every marsh and spring, in this poem of re-creation, becomes a former crag and flint; every knoll a kicking lamb.

If a reader craves some schema to differentiate and order modes of interpretation, what could be more helpful than asking hard simple questions? What does a poem say and how? When and where, with what and for whom? Why? How does it differ from what I thought it would say? Why this with that? What’s missing? And the question that surges through Turgenev and Tolstoy and beyond, what is to be done, what to do? All other schemas impose.