* * *

For all its shifts of perspective and varied liturgical work, Psalm 115 coheres around a pair of emphatic oppositions: the horizontal separation between “us” (1, 18) and “others,” the goyim (2) who worship appearances; and the vertical poles of skies (3a, 15b-16a) and earth (15b-16). These oppositions cross, creating quadrants: we under our God; they under, what? Nothing? Or under the God who is not theirs but ours?

The psalm begins and ends with the first-person plural. This “we” at first opposes not “the others,” but the Lord: “Not to us Lord | not to us / oh only your name | give a glow” (1). Only then do the goyim, other cultures, appear. “How long | must the others say / where pray tell | is their God” (2). From these others’ perspective, the “we” of the poem are a “they,” which allows the line “where is their God” to work in both directions, as their foolish, stated question and our wise, unstated one. At the end of the psalm, “they” are aligned with “the dead” and “all | who sink to silence” (17), whereas “we | adore the Lord / from now | on till ever” (18). Our quadrant, opposed to theirs and differentiated from the Lord’s by the work of adoration, lasts.

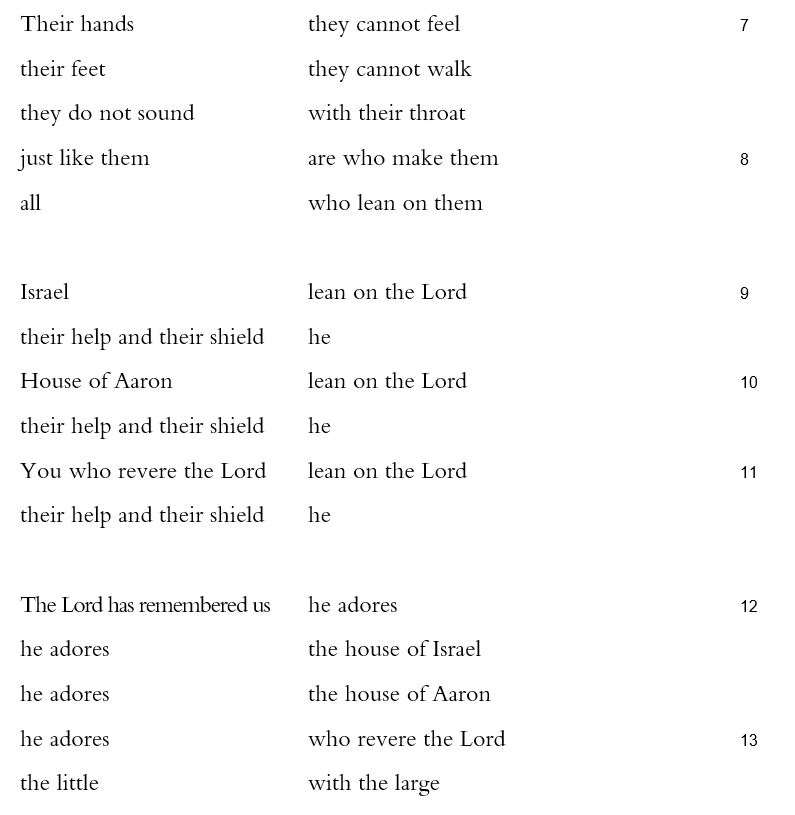

The Lord, by contrast, sees “us” as “you.” The psalm’s implied speaker gives a benediction, a blessing, in verses 14-15: “May the Lord | add to you / to you | and to your children / may you be adored | by the Lord.” The lines before this have just clarified the vertical relationship between “us”/”you” and “the Lord” through the triple imperative, “lean on the Lord” (9-11), and the quadruple declarative, “he adores” (12-13). Though “we,” too, “adore the Lord” (18a), the others, “they,” “lean on them,” their totems”: “just like them | are who make them / all | who lean on them” (8). The Lord’s quadrant, we learn, includes “the skies | the skies of the Lord,” in contrast to “the earth he gave | to mortals” (16). All the skies, theirs and ours, are the Lord’s. All the earth is ours, though we share it with them, who are as inanimate as their totems.

At first glance, the psalm seems a collage. Its parts do different things. If liturgy is, as its etymology suggests, the ergos of the leios, the work of the people, the pieces of Psalm 115 do different work, make different things happen. Verse 1 performs subservience by abnegation. Verse 2, “How long,” calls for revelation as proof against others. Verse 3 affirms allegiance and claims superiority. Verses 4 through 8 adore the Lord by denigrating alternatives. Verses 9-11 adjure; verses 9-13 proclaim. Both proceed by tightening the circle of the faithful, from “the house of Israel” to “the house of Aaron” to those “who revere the Lord.” Verses 14-15 bless and pronounce. And verses 16-18 carve out space for the people’s demonstration of commitment. Unlike the Lord in the skies, unlike those “who sink to silence” (17b), “we | adore the Lord” (18a.)

It takes little imagination to see these segments of the psalm as originating in the experience of worship, as patterning a service. After all, Psalm 115 is part of the Hallel sequence. And it is the Christian hymn “Non nobis.” The lines do not just resemble liturgy; they are liturgical. But the work of the people that these lines accomplish goes beyond their recitation and their being sung. The work these lines do is division. The psalm protects these people from the others’ questioning by relocating the Lord to the skies, away from the earth. It preserves the Lord’s glow, away from the people, by the work of adoration. Most importantly, dangerously, it works to value both the Lord and the people by devaluing all others as senseless, hollow, speechless, as good as dead.