* * *

Something happens over the course of this psalm, a remarkable change that’s easy to miss by those who know only excerpts. “The Lord is on my side,” untold millions say, seeking soothing, quoting the King James translation of Psalm 118:6, “I will not fear.” Verse 22, “The stone | the masons scorned / has become | the cornerstone,” is similarly recited in one version or another at countless services, the image of the cornerstone showing up especially in evangelical Christian communities. Likewise, verse 24 is well-loved by liturgists with its tetrameter and slant rhyme in English, and it appears on t-shirts, tote bags, and coffee cups: “This is the day that the LORD has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it,” according to the ESV. Psalm 118 itself, however, is not a compilation of hits, but a ceremony, or at least part of one, and marks an important transition.

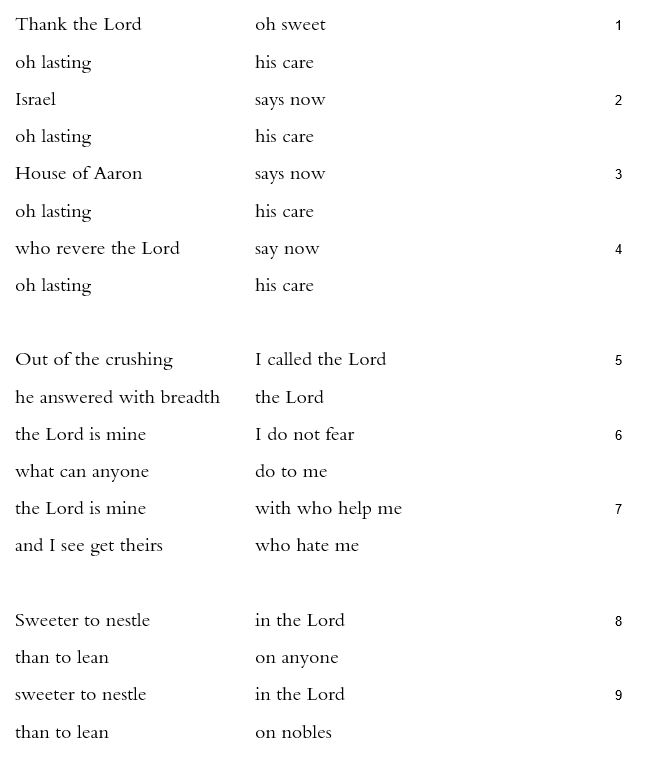

The exact nature of the transformation is harder to pinpoint, though the psalm’s contours show pivotal moments in the rite. After the fourfold beginning, “oh sweet / oh lasting | his care” (1-4), a first-person speaker testifies to having called for help (5), demonstrating her allegiance to the Lord rather than to anyone else:

The Lord is mine | I do not fear

what can anyone | do to me

the Lord is mine | with who help me

and I see get theirs | who hate me (6-7).

Here and in the verses that follow, she distances herself from these others, from “anyone” (6, 8), from “who hate me” (7), from “nobles” (9), and from “all the others” (10). She affirms instead her loyalty to the Lord, whom she names nine times in eight verses (5-12). Her separation from the others marks a pivotal moment, punctuated by the fourfold repetition of “circled me” (10, 11 x2, 12) and the tripled refrain, “oh I cut them off” (10, 11, 12). For readers and reciters, these refrains underscore significance. For the speaker, they seem more like a present-tense performance than a promise of future parting. The verb “to cut off” is the word for circumcise, suggesting a ritual of joining and separating as well as an apotropaic rite (cf. Exod 4:24-26).

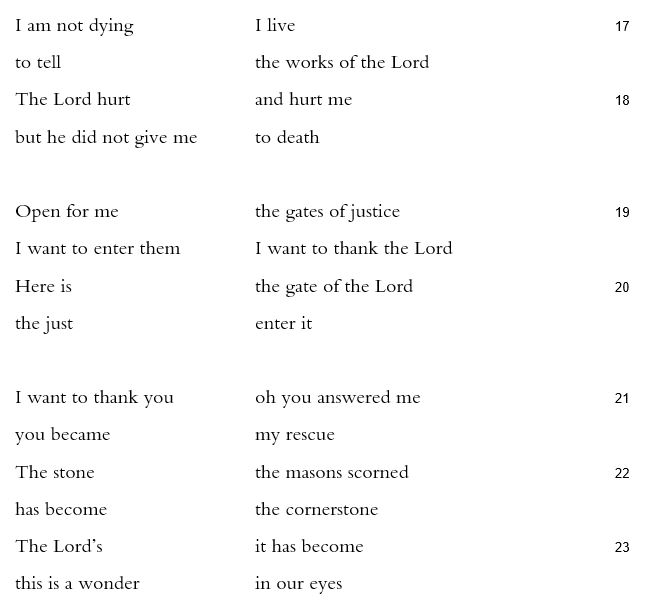

Not that Psalm 118 necessarily originated from a context that included actual circumcision, though Hermann Gunkel argues persuasively that the psalm’s earliest context may have been a conversion practice, a liturgy for proselytes. It’s valuable, at least temporarily, to read the speaker’s voice in this psalm as the voice of a convert, someone underdoing a painful but valued change. This reading makes sense of the psalm’s next major section, verses 13-18, which begin and end with the same grammatical structure and violence: “You shoved and shoved me | to fall” (13a) and “The Lord hurt | and hurt me” (18a). This violence is repeated and underlined, but it is not lethal: “but the Lord helped me” (13b), “I am not dying | I live” (17a), “but he did not give me to death” (18b). Here, at the center of the psalm, there is ritual simulation of violence: “sounds of shouting and rescue | in the tents of the just / the right hand of the Lord | showing force” (15). Whether this is a convert’s transformation, or a collective ceremonial commitment, the pattern is clear: brutality marks the movement from outsider to insider, marking the moment when the speaker quotes the Song of the Sea, Israel’s most important collective celebration of separation: “my strength and song | the Lord / he has become | my rescue” (Ps 118:14, Exod 15:2). Thus the “gates of justice” and “the gate of the Lord” in verses 19 and 20 become the historical threshold from Egypt to Sinai to the land, as well as the doorway of allegiance from “them” to “us.”

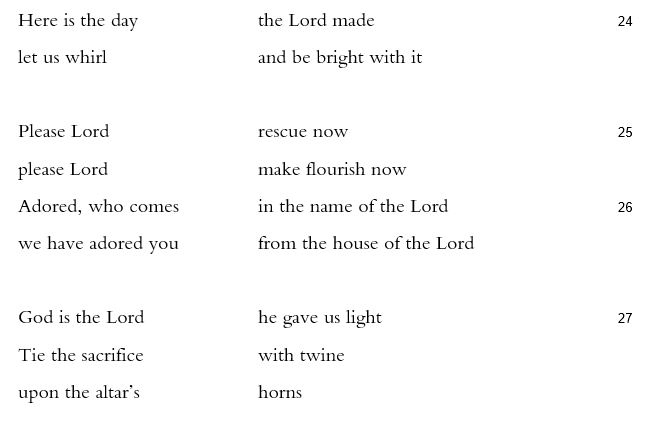

Verses 20-24 feature three demonstrative pronouns/adverbs: zeh (20), zot (23), and zeh again (24). Each use points to something in the present tense; “Here is | the gate of the Lord” (20), “This is a wonder | in our eyes” (23), “Here is the day | the Lord made” (24). In these same verses significant verb hayah, “to become,” appears three times. This series began in verse 14 (“he has become | my rescue”), and continues with “You became | my rescue” (21). It culminates with the refused stone that “has become | the cornerstone | the Lord’s | it has become” (22b-23a). Together, these gesturing words and the verb of becoming mark another pivotal movement, a movement of becoming that is as fleeting as a day and solid as stone, as emphatically present tense as it is historical, “this is a wonder | in our eyes.”

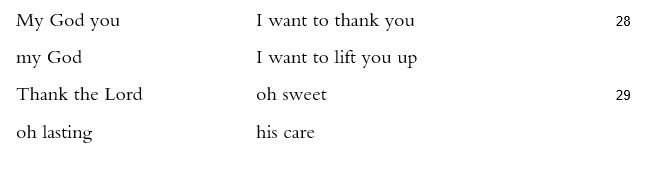

Again, the exact parameters of the speaker’s experience are unclear. So are any number of specific questions about the ending of the psalm. Who speaks which lines? Who all or what all is the Lord being asked to “rescue now… make flourish now” in verse 25? Are the stage directions in verse 27, to “tie the sacrifice | with twine,” to be sung as well? When the first-person singular speaker’s voice returns in verse 28, she quotes the second part of Exodus 15:2, but transforms those lines into direct address. Instead of “this my God | I want to dwell with him / God of my father | and I want to lift him up,” she says, “My God you | I want to thank you / my God | I want to lift you up.” An atom of the Song of the Sea has been split. The first half of Psalm 118 seems to precede the powerful moment in which the Lord “has become | my rescue” (118:14, Exod 15:2). The second half of the psalm, then, reenacts in liturgy the powerful moment between the two halves of one verse of Israel’s most famous ancient poem, that moment between rescue and thanks, filling it with the cornerstone of the temple, with the altar, and with the wonder of the present tense.