(a song of steps)

* * *

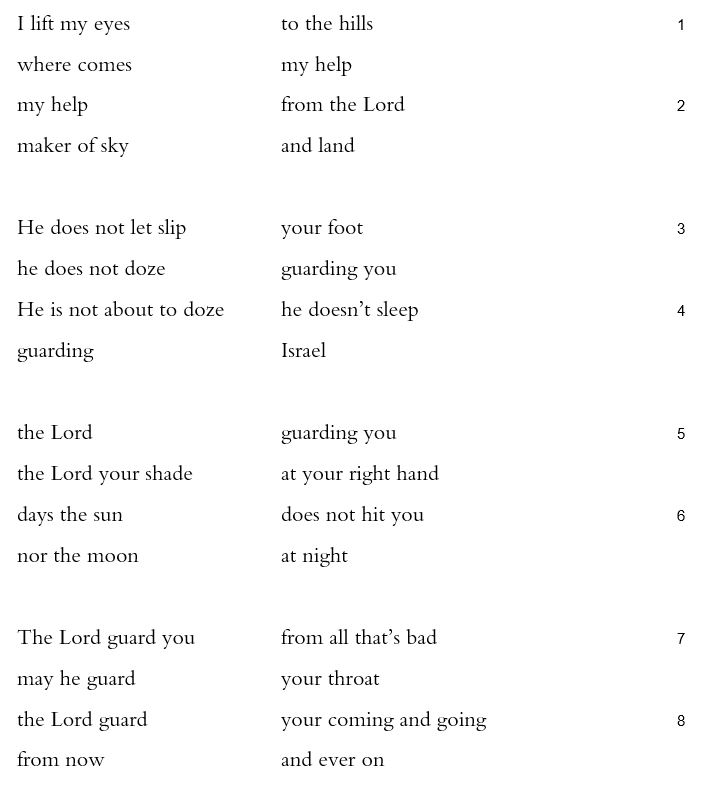

One can live with words a long time and not see them for all they are. Psalm 121 is sung and said so often and its care runs so deep and clear it is easy to miss its more-than.

At first glance or at five hundredth, the psalm’s gestures of comfort are plain. A person needs. She yearns. She lifts her eyes up the ridgetops to the ranges where earth and air meet, “to the hills” (1) at the edge of “sky | and land” (2). In most English translations, she asks where her help comes from. In the King James Version, she assures herself that her help does come from the hills. The Hebrew is ambiguous. A good director might suggest the actor deliver the psalm’s first verse equal measures worry and pep talk: “where comes | my help.” Verse 2, likewise, could be delivered by a skilled actor as half an assertion— “my help [is] | from the Lord” (2a)— and half a continued question: “where comes | my help / my help | from the Lord” (1b-2a). In measures, the psalm registers both confidence and anxiety, in its gesture of lifting eyes.

Verses 3-8, the rest of the lyric, rely on the comforting gesture of benediction pronounced by a second person, who identifies the Lord as a watchkeeper, a guard. Three times this second speaker, a priest or parent or other voice, uses the participial form of the verb shamar: “guarding Israel” (4b), “guarding you” (3b, 5a). Three more times, this second speaker puts the same verb into the prefixed form, somewhere between present and future declaration or jussive modality: “The Lord guard you” (7a), “may he guard” (7b), “the Lord guard | your coming and going” (8a). These six guardings accompany four uses of the name “Lord” in the psalm’s last five verses.

Between the two guarding triplets is a figure for God that haunts as much as it comforts, the tsel of verse 5, a shadow or shade, a covering darkness: “the Lord your shade | at your right hand.” Such companionship consoles as it protects, shielding from burning sun as well as from the baleful influences of the moon. But it lurks as well, a constant fellow traveler of the dusk. In his essay “Ascent to Darker Hills,” biblical scholar and poet Karl Plank has written insightfully of the ambiguity of verse 1’s hills as danger and shelter both and of how the Lord’s dark shade in verse 5 conceals more than it reveals, half-answering the first speaker’s early half-question with simultaneous presence and absence. The image, Plank writes, “returns one to the threat of constriction, of being trapped within the very bounds that have given refuge” (163). This is not at all to deny the psalm’s comfort. Instead, it is to celebrate both of the psalm’s humane gestures: the first speaker’s attempt to assuage her own fear, and more, the second speaker’s efforts not just to reassure, but to acknowledge the dark.