(a song of steps)

* * *

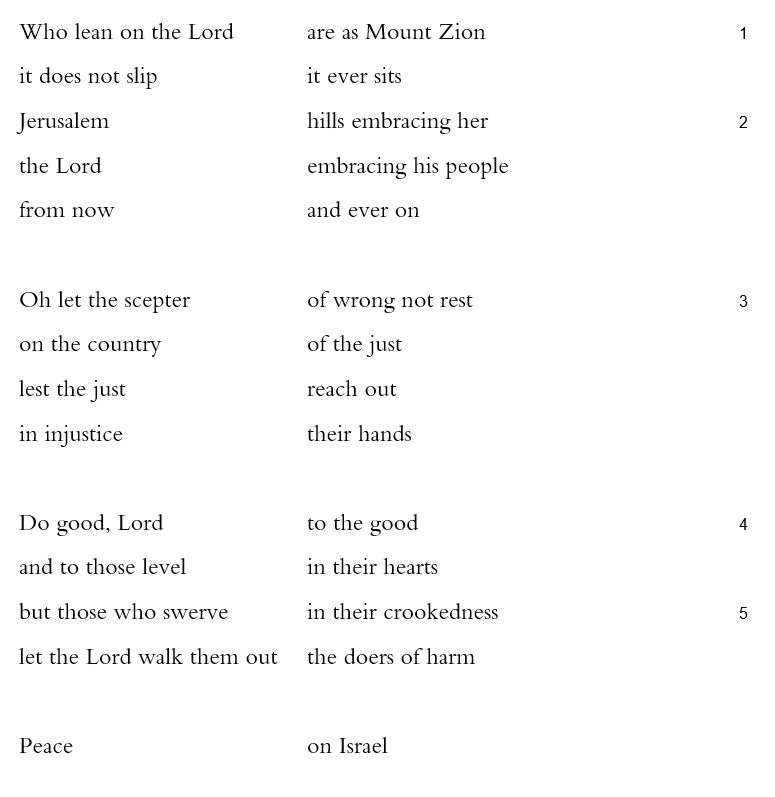

It’s easy to miss how strikingly revisionary is the image that begins Psalm 125. Ordinarily, Mount Zion is depicted as the Lord’s home, his house, his throne (see for example, 1 Kgs 8, especially verses 11-14; see “my hallowed hill” Ps 2:6; “the Lord | who sits in Zion” Ps 9:11; “great in your center | the hallowed of Israel,” Isa 12:6; see also Zech 2:10-11) Towards Zion centripetally, usually, the people come (see Isa 51:11; Jer 3:14, 31:12, 50:5; see Zech 8:3-8). Here in Psalm 125, however, it is the people who are like Zion. The mountain’s lasting stability is compared to their trust: “it does not slip | it ever sits” (1). The Lord, by contrast, has radiated out to the hills centrifugally: “Jerusalem | hills embracing her / the Lord | embracing his people” (2).

The image registers displacement and foreign occupation without the need for figures of absence or rupture, a divine chariot or silence. Rather, it is trust itself that’s centered, a mount encircled by hills that never move. With the Lord rippled out to the hills, the center is instead occupied by “the scepter | of wrong,” a governance which the speaker prays will be only temporary (3a). Why? “Lest the just | reach out / in injustice | their hands” (3c-d), the psalm continues, powerfully extending the scepter, an extended arm, to the extended arms of the people. Unwanted rule, a scepter of wrong, multiplies its wrongs, either by licensing the masses to do wrong or by inciting the just to revolt.

The first stanza centers loyal followers within an embracing, constant Lord; the second centers an unjust ruler within the encircling hands of the corruptible just. The third stanza, verses 4 and 5, takes something from each of those first two. Contrasting “the good” with “the doers of harm,” those “level | in their hearts” with “those who swerve | in their crookedness” (4-5), the psalm ends by mapping permanence against impermanence, alignment against veering off, good against bad. Fittingly for one of the “songs of steps,” it relies on the common verb “to walk” as it invites the Lord to show the bad the door. If there were a colonizing censor, Persian or Hellenistic, who scoured this psalm for evidence of sedition, it would have be easy to miss or dismiss how subversive is Psalm 125’s closing call for “Peace | on Israel.” “Do good, Lord | to the good” sounds even more innocuous, merely more retributive justice in the texts of an occupied people. As verses 3 and 5 make clear, however, this is a notice of eviction.

And yet, because rhetorical figures unleash energies beyond intent or control, the image of the trusting as more central even than God and the image of a scepter as wrong both take on lives of their own. What could be more anti-establishment, more— to borrow twenty-first century parlance— disruptive, than the paired wish to “let the scepter | of wrong not rest” and “let the Lord walk them out”? Mount Zion might not physically move except in tectonic time, but that scepter will never be trusted again. “Peace | on Israel,” indeed.