(a song of steps)

* * *

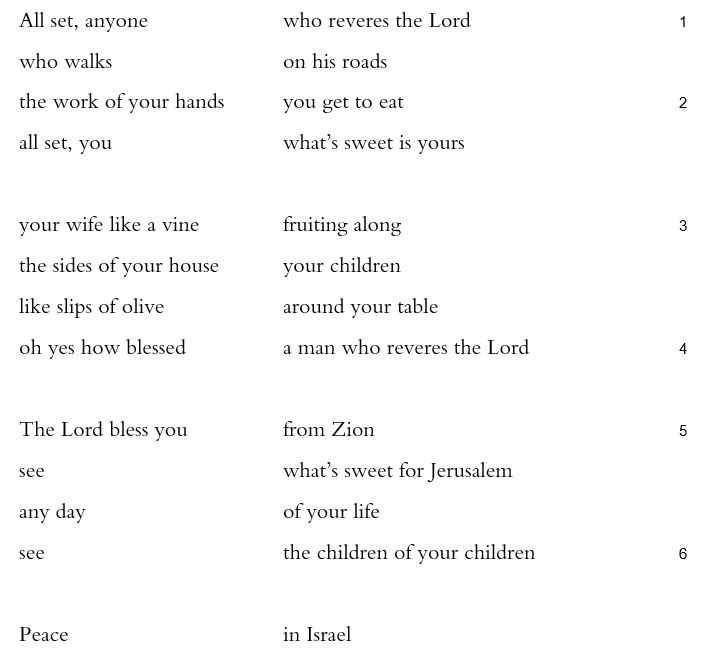

In contrast with Psalm 127, to which it seems a linguistic and thematic retort, Psalm 128 does not imagine deploying children from private home to public gate, the domestic against the civic, as in combat. The prior psalm began by doubting divine support for communal projects before claiming, tautologically, that human fertility is God-sanctioned beyond dispute: the Lord may not want urban development, but each son is a sign that the Lord wants sons. This psalm, however, sees family and community, private and public, as aligned. In Psalm 128, the domestic happiness of “anyone | who reveres the Lord” (1) comes as a consequence of that reverence. Maternity is restored. Children here are olive trees (3), not arrows. And most importantly, reverence and fertility are followed by blessing and by a vision in which “what’s sweet is yours” (2) becomes “what’s sweet for Jerusalem” (5). The psalm ends not with conflict but with “Peace | in Israel” (6).

The psalm is shaped first by two “all set” phrases—responding to “All set, the man | who has filled / his quiver | with them [sons]” from Psalm 127:5—in Psalm 128:1 and 128:2: “All set, anyone | who reveres the Lord” and its partner, “all set, you | what’s sweet is yours.” These two expressions of fulfillment give way to two expressions of blessing: “look oh how blessed | a man who reveres the Lord” (128:4, which doubles both “the man,” haggeber, from 127:5, and “who reveres the Lord” from 128:1) and “The Lord bless you | from Zion” (128:5). Both the “all set” phrases and the blessing phrases move from third person to second person, moves of immediacy. That same intensification occurs in the psalm’s last two repetitions. “Your children” in verse 3 become “the children of your children” in verse 6, while the two payoff imperatives, “see | what’s sweet for Jerusalem” (5b) and “see | the children of your children” (6a), repeat the shift of person and of scope.

That culmination in seeing is registered by a deft pun, Psalm 128’s response to the ben/banah and shav’/sheina’ puns of Psalm 127. The one “who reveres the Lord” (128:1, 4) is the yir’ei-adonai. The “see” imperatives of verses 5 and 6, introduced by a vav to register purposiveness, are ur’ei: “see | what’s sweet for Jerusalem,” “see | the children of your children.” Reverence yields vision, the yir’ei – ur’ei connection implies.

If, as seems likely (see Psalm 15 introduction), the category of the yir’ei-YHWH indicated converts to worship of the Lord during the Second Temple Period, the contrast between Psalms 127 and 128 becomes even more pronounced. While Psalm 127 applauds patriarchs for siring soldiers, militarizing the family against “enemies | at the gate” (127:5), Psalm 128 invites outsiders in, where they participate not only in generativity, but in nourishment. “The work of your hands | you get to eat” (128:2a) is an easy line to overlook, but its promise must have felt very real for a whole underclass of citizens. As Karen Armstrong notes in The Lost Art of Scripture, the ancient Near East was not exactly known for laborers who ate the work of their own hands:

“Sumerian aristocrats and their retainers—bureaucrats, soldiers, scribes, merchants and household servants—appropriated between half and two-thirds of the crop grown by peasants, who were reduced to serfdom. They left fragmentary records of their misery: ‘The poor man is better dead than alive’, one lamented. Sumer had devised the system of structural inequity that would prevail in every single state until the modern period.” (19-20)

(“Until the modern period.” Hm.) “Within their walls | they squeeze the oil / tread the wine troughs | and thirst,” Job rages (Job 24:11). Against this injustice and in keeping with the prophetic claim that the Lord aligns with victims rather than oppressors, Psalm 128 offers its vision of “what’s sweet” to “anyone | who reveres the Lord.”

It would be negligent not to add that to the writers of Psalm 128, this “anyone” was clearly male, a father whose worth was measurable by family size. My translation here opts for a strange compromise. Both 127 and 128 use the word for male offspring, literally “sons” rather than “children.” Erasing all gender from Psalm 127— a quiver full of children— would lose what that psalm clearly intends— a patriarchal family that only counts its fathers and sons. It would also leave out what Psalm 128 does to challenge and correct Psalm 127, adding back “your wife” to the depiction of fertility. Because Psalm 128 is more inclusive, “your children / like slips of olive | around your table” (3b-c) registers that inclusivity more than “your sons” would. Because the psalm is nevertheless a product of its time, “your spouse like a vine | fruiting along / the sides of your house” (3a-b) would mischaracterize its gender politics, which are fraught with, for example, the common biblical mirroring of woman and nature. What’s needed is to appreciate Psalm 128’s rejoinder to the prior psalm as close to precisely as we can, not assuming it will be equally appreciable or quotable by every one of its readers, whose experiences in the world differ.