(a song of steps)

* * *

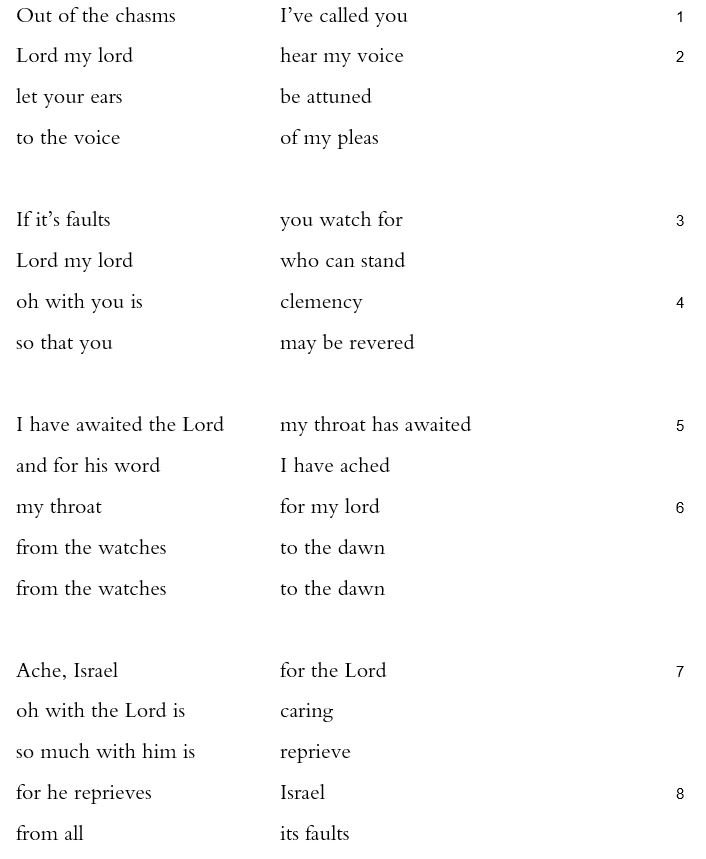

The least penitent of the traditional “penitential psalms,” Psalm 130 twice follows a stanza of poignant experience with a stanza of theological reflection. The first stanza (verses 1-2) deepens the typical opening of a psalm of lament, while the second (3-4) describes the Lord as forgiving, not fault-finding. The third stanza returns to the first-person in passionate expectation (5-6); the fourth converts that personal energy to a characterization of the Lord as pardoning (7-8). There is not a single note of remorse or apology in Psalm 130, no sackcloth or self-flagellation. It is a crying from deep chaos, a throat that hopes in the dark, and an argument that the omnipresence of wrong cannot be met by divine prosecution, but only by acquittal and care.

The first stanza doubles the word “voice” and adds “my lord” to the name of the Lord as it borrows conventions from other psalms of complaint: the speaker’s call (e.g., 4:1, 28:1, 141:1), the imperative to hear (17:1, 61:1, 102:1), intensified by the audience’s “ears” (e.g, 31:2, 71:2; 86:1; 88:2). It is that first half-line, “Out of the chasms,” literally “From the deeps,” that gives this psalm particular strength: a preposition before a place, a place before a person or sound. Scores if not hundreds of choral compositions have been made of that phrase, De Profundis in Latin. In Hebrew, the word is mimma`amaqim, which works the entire mouth except the front of the tongue, with opening and closing buzzing lips in the sequence of m’s, alternating with those three low vowels in a row, ah-ah-ah, deepened by the `ayin and qof, pronounced at the pharynx and uvula, all between two high vowels that start and end the word, ee and ee: mimma`amaqim. The watery abysses the word indicates are not the fires nor shades of some punitive underworld or putative afterlife, but the primordial depths of chaos. Psalm 129 began by figuring oppression as the noose of a siege. Psalm 130 begins from trauma as the lowest of lows. It asks the Lord not just to hear, but to render the Lord’s ears attentive, “attuned,” a late, precise adjective (used elsewhere only in Nehemiah and in 2 Chronicles, though the verb is older) that calls on the Lord to adjust to the voice.

Another late, precise abstraction arrives in the second stanza in the word “clemency” (elsewhere only in Nehemiah and Daniel, though again the verb is older). Only in the repetition of “Lord my lord” (1-2, 3) does the second stanza invoke the first-person. Rather, the stanza is insistently second person:

If it’s faults | you watch for

Lord my lord | who can stand

oh with you is | clemency

so that you | may be revered (3-4).

Explicit markers of reasoning— “if,” “oh” [or “because”], “so that”— make clear that the move away from the immediacy of first-person experience is part of an inductive argument, a generalization after evidence. Put deductively, its theology seems to be that God’s desire for reverence necessitates forgiveness since, we infer, guilt exempts no one and thus watchfulness for guilt must be a long, lonely task that triggers nothing like reverence. Far from depicting or enacting penitence, the first half of Psalm 130 attunes the Lord’s ears by obviating fault-finding altogether.

Where the first and second stanzas both say “Lord my lord,” the third repeats the phrase, but inserts whole lines inside:

I have awaited the Lord | my throat has awaited

and for his word | I have ached

my throat | for my lord (5-6a).

Here the poignancy comes from repetition, which underlines the experience of waiting, and from the return of the first-person, intensified by the repeated metonym for the self, the throat (5a, 6a). The stanza’s doubling continues in the repeated line “from the watches | to the dawn” (6b, 6c), which could equally well be rendered “more than watchers | for the dawn.” The worry from the second stanza that the Lord might be the one “watching” for faults here returns, but is exceeded by the speaker’s own expectancy and desire. We have not left the dark chasms. We just feel them now not as space but as time passing slowly.

The final stanza retrieves the ache (5, 7) as well as the faults (3, 8) only to dismiss them both. Now it is Israel in the second person, the Lord in the third person, about whom theological claims are made: “oh with the Lord is | caring / so much with him is | reprieve” (7b-c). The Lord’s care compensates for the speaker’s yearning, just as the Lord’s “reprieve” takes care of the speaker’s, and all Israel’s, faults. The resolution is both abstractly theological and personally felt.

Perhaps the most affecting feature of this final stanza and of the psalm as a whole is its rejection of a narrative solution, any convenient closure that would have tidily ended this speaker’s cries. This is no facile “I cried; you answered” psalm. It is an “I suffer; with the Lord come clemency and care” psalm. It neither ignores suffering nor wishes it away. Instead it responds by utterly separating trauma from fault, marking as divine attributes caring and pardon.