(a song of steps)

* * *

Readers of ancient texts have to be especially alert to the time axis, that horizontal arrow that traces the production and reproduction of cultural memory. In hymns about foundational figures, for example, there is the t=0 of the moment of writing, a point that stretches to a line segment for songs with complicated composition histories. To the left or negative side of t=0 lie those events and motives that hymns half-remember/half-create, as well as the distance (the time) between those moments and composition. We ourselves lie to the right or positive side, celebrants, preservers, students, critics, analysts of tradition, since our readings, too, take place in time. To understand Psalm 132, in other words, the axis of time helps distinguish the unknowable actual King David from the David of the books of Samuel and Kings; the David of Chronicles from the David of Psalms; David in the centuries before, during, and after the Babylonian Exile of the 6th c. BCE, as opposed to the Davids of Rabbinic Judaism and early Christianity or the Davids of the mercantile and monarchical European Middle Ages, or those Davids invoked by defenders of 21st century theocracy and kakistocracy. Always the question: who makes what memories to what ends?

So, when Psalm 132 begins by asking the Lord and thus the audience to “remember Lord | for David / all | his humblings” (1) and to remember David’s promise not to rest until Israel God’s can rest (2-5), who is reminding whom of what, and why? With no clear referent, David’s alleged abasements could indicate almost anything in his biography, from fugitive folk hero to King of Judah to King of Israel as well, watching so many of his enemies and sons die. David’s comedowns could be personal failings or political setbacks, or they could be successful displays of public humility (most recently imagined in Psalm 131).

David’s oath, for its part, is an evident invention, an elaboration rather than a recollection. Both the Deuteronomistic History (1 Samuel 4-7 and 2 Samuel 6-7) and 1 Chronicles 13-17 follow the movement of the Ark of the Covenant, culminating with David’s role in establishing what David in Psalm 132 calls “a place | for the Lord / a tabernacle” (5). According to both of the narrative works, David took Jerusalem for his capital, then moved the ark there from Kiriath-Jearim. And only then, “when the king sat in his house, and the LORD had given him rest round about from all his enemies” (2 Sam 7:1; cf. 1 Chron 17:1), did David say to the prophet Nathan, elliptically “See now, I dwell in an house of cedar but the ark of God dwelleth within curtains” (2 Sam 7:2; cf. 1 Chron 17:1). In both 1 Chronicles and 2 Samuel, however, God rejects David’s implied offer to build a temple, instead deferring that responsibility to “one of your own sons… He is the one who will build a house for me” (1 Chron 17:11-12). Psalm 132 inverts both sequence and emphasis. In the psalm, David is determined not to rest until he finds “a place | for the Lord / a tabernacle” (5). If the Lord’s place is Jerusalem as a whole, David’s mission has already been accomplished, according to the narratives. Yet if “a place | for the Lord” means the temple in particular, nevertheless the narratives state that David has already rested in his palace and that God demurs at David’s desire to build a temple. This remembered vow in Psalm 132 idealizes David even more than Chronicles does, even more than strands in Samuel do, aligning him almost entirely with God’s desires. To do so, the psalm asks God to remember words David never said.

The attentive reader will note with interest that the verbs in David’s oath here all appear in the David narratives of Samuel and Kings, just not in ways one might expect. “I mount,” ’e`eleh (2 Sam 2:1, 19:34), “I give,” ’ettein (2 Sam 5:19, 21:6; 1 Kgs 3:5), and “I find,” ’emtsah (2 Sam 15:25, 16:4), all show up in both psalm and stories. The word ’abo’, “I go into” (3), is used by David once in the Deuteronomistic History, in the negative, when he tries to persuade King Achish of the Philistines to let him enter battle against King Saul (1 Sam 29:8). The same word is used in two other significant places. First, by Uriah, David’s loyal soldier, as he foils David’s attempt to cover up his crime with Uriah’s wife Bathsheba by sending Uriah home:

Uriah said to David, “The ark, and Israel and Judah are sitting in tents, and my lord Joab and the subjects of my lord are camping on the ground in the field, but I should go into my house to eat and drink and lie down by my wife? By your life and the life of your breath, I will not do this thing.” (2 Sam 11:11)

Later, when David is old and probably senile, the prophet Nathan uses ’abo’ in conversation with Bathsheba, orchestrating the scene with David that will land her son Solomon on the throne:

“Go on and go into King David. You’ll say to him, ‘My lord the king, did you not vow to your subject saying, oh, Solomon your son will be king after me, and he will sit on my throne? Then how is Adonijah king?’ And while you’re still there talking with the king, I will go in you after you and fill out your words.” (1 Kgs 1:13-14)

If these are three coincidences, they are certainly meaningful. None of them shows David at his best. All of them turn on dishonest vows—David’s double-dealing with Achish and Saul; his violation of both Bathsheba and Uriah, contrasted with Uriah’s vow of loyalty; and Bathsheba and Nathan’s manipulation of David, which, while not technically a lie (“did you not vow?”), nevertheless asks David to remember words he never said, a promise he appears not to have made.

Through the first half of the twentieth century, most scholars argued that the archaic language of Psalm 132 meant an early date of composition. But like many things, monarchies are idealized when they no longer exist. The David of this psalm really only makes sense, most scholars now would agree, as a product of post-exilic cultural imagination, as a signifier of unity, centralization, and as an alternative to some “scepter | of wrong.” A key question, Kraus writes of Psalm 132, is how the Ark of the Covenant came from Sinai to rest at Zion. That does indeed seem to be something that pre-exilic audiences might want to hear answered, alongside questions like these: where was David when Saul was killed? How did David come to hold Saul’s crown? How exactly did Solomon gain the throne? If David was chosen, why did he not build the temple? Later audiences, after the destruction of Solomon’s temple, must have asked what happened to the ark and to the divine presence in Jerusalem? After the return from the exile, by contrast, audiences must have wondered why, without a monarchy, centralized worship in Jerusalem still mattered. Psalm 132 seems disinterested in all of those questions except this last: why still visit Zion without a king to compel us? Maybe no question matters more to the book of Psalms.

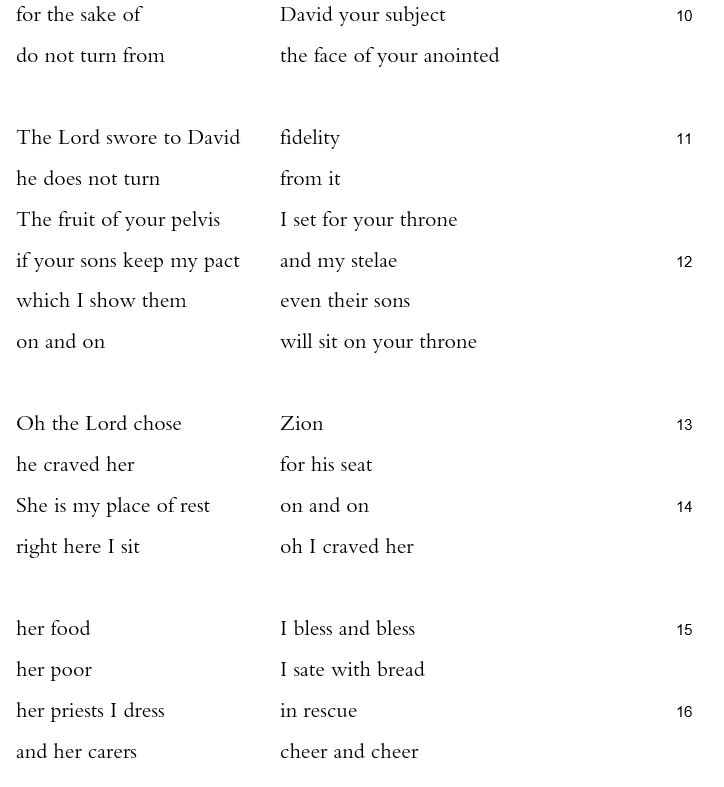

Why? First, it was David’s vow and his disposition that led the Lord to promise, the psalm answers, presenting two parallel vows, David’s in 1-5, the Lord’s in 11-12 and 15-18. Second, the Lord loves Zion (13-14) and promised to take care of her (15-16). And finally, there is the Lord’s promise to perpetuate David’s lineage, which was both unconditional (“The Lord swore to David | fidelity / he does not turn | from it,” 11) and conditional (“the fruit of your pelvis | I set for your throne / if your sons keep my pact” (11c-12a). That means, for its earliest audiences, the psalm invoked and invented memories of David for the sake of Zion’s centrality, something it could do only if David was already the subject not of memory but lore and if monarchy was a matter of the past.

Indeed perhaps the most telling lines in the psalm are those that deal with the priests and the chasidim, the ones who care and are cared-for: “May your priests | dress in justice / may your carers | cheer” (9) and “her priests I dress | in rescue / and her carers | cheer and cheer” (16). The psalm may dangle a symbolic messianic hope at the end, a horn, a lamp, and a flowering crown, but the true heroes of the psalm are not future kings, but present-tense priests, the makers of memories.