* * *

The liturgical postures of benediction and praise can seem to overlap, especially in standing and in the raising of hands. But blessing kneels and bows for what’s to come, while lauding sings loudly for now and what’s been. Psalm 135, which blends the two modes of worship, also spends a third of its verses memorializing the Lord’s repeated interventions on Israel’s behalf, less for timelessness or the sake of the past than for the community’s immediate future, its desire to unseat its contemporary opponents, current versions of pharaohs and kings.

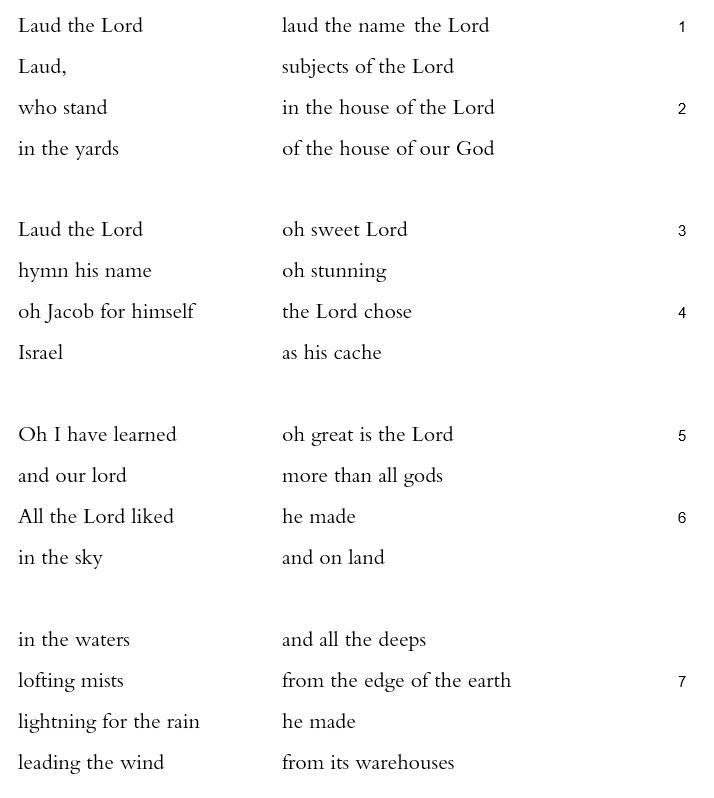

The psalm feels very much like an expansion, an explosion, of the psalms that precede it, into which have been inserted bits and passages from all over, the whole thing introduced with formulas of praise. “Laud the Lord | laud the name the Lord,” the psalm begins (135:1), urging those who just, in the previous psalm, blessed the Lord (“all subjects | of the Lord / who stand in the house | of the Lord by night” 134:1) to now praise: “Laud, | subjects of the Lord / who stand | in the house of the Lord / in the yards | of the house of our God” (135:1b-2). The next verse reaches back to Psalm 133, repeating the words “sweet” (tov) and “stunning” (na`im), only paired in these two verses (133:1, 135:3; cf. 147:1). The prior psalms’ forward-looking blessings have become Psalm 135’s backward-looking praise. The psalm reaches back all the way to creation (135:6-7) and to Exodus (135:5 || Exod 18:11; 135:8 || Exod 12:12; 135:13 || Exod 3:15) and Deuteronomy (135:4 || Deut 7:6, cf. 32:9; 135:10-11 || Deut 4:46, 31:4; 135:12 | Deut 4:38 and often; 135:14 || Deut 32:36). Other psalms and poetry also appear to be included, by quotation (135:7 = Jer 10:13, 51:16) and near-quotation (135:6 || 115:3) , though determining the direction of allusions is often educated guesswork. Does Psalm 136:17-22 quote Psalm 135:10-12 or vice versa? In the case of Psalm 115:4-11 and Psalm 135:15-20, it’s logically simpler to assume that Psalm 135 adds the Levites in 135:19 than to explain why Psalm 115 would leave them out. And it is far simpler to assume that Psalm 135:17b energizes and extends the expected “a nose theirs | they do not smell” of 115:6 to “a nose—there is no | breath in their mouths.”

That Psalm 135 gathers quotations is clear. But to what end? Verse 11c offers one subtle clue. The common biblical phrase is “all the kingdoms of the earth” (Deut 28:25, 2 Kgs 19:15, 19; Ezra 1:2, Ps 68:32; Isa 27:16, etc.) which this psalm localizes in a phrase unique in the Bible (though an individual king of Canaan is named in Judges 4) “all the kingdoms | of Canaan.” A line that marks “all the kingdoms of the earth” as Israel’s inheritance could easily be perceived as a threat to any foreign ruler. A second hint comes in verse 14’s partial quotation of Deuteronomy 32:36 which omits the crucial next words: that the Lord governs “when he sees that [Israel’s] hand is spent: no one, chained or freed.” The implication here, too, is perfectly clear to any reader who knows the quoted passages: the providential theology of overthrowing rulers and taking back lands is alive and well. The psalm may begin with the fourfold imperative “laud” and end with the fourfold imperative “bless,” but its real work lies in its subversive core. The final lines of veneration— “May the Lord be blessed | from Zion / who lives in Jerusalem | Laud the Lord” (135:21)— offer blessing and praise as a pair. But their pairing of history and hope is just as significant, and potentially just as subversive.