* * *

No psalm haunts more than this, among the most poignant poems of the horrors of war. David may have slain his ten thousand. Achilles may have his epithets, his tent and shield. But this song sings as it says it cannot, turning tears to gruesome smiles, aching through remembered trauma, lashing out in a howl for justice. It is a psalm of mothers who relive their rape and grieve their murdered children.

The narrative situation, set in medias res in the Babylonian Exile of the 6th century BCE, works in three temporal directions. In its present-tense scene, captives from Jerusalem are made to remember their home and forced to sing when they wanted to cry. The central narrative question for the present tense is whether they will comply with their jailers’ requests, and if so, what song they sing: “Ah how can we sing | a song of the Lord / on a land | so strange” the psalm sings, with performative irony (4). Or perhaps verses 5-6 are lines of the song they sing, “If I forget you | Jerusalem” and following.

At the same time, the psalm glimpses hypothetical futures even as it flashes back to snapshots of terror from the destruction of Jerusalem. “If I forget you” does at least quadruple duty, then. As an “if” it’s a worry. In Hebrew, an ’im also marks a vow: “I swear I won’t forget you.” Narratively, it seems like a line from the song the captives sing. For us, it is a line of the psalm, a song, a line that makes sure we the readers don’t forget, every time we sing.

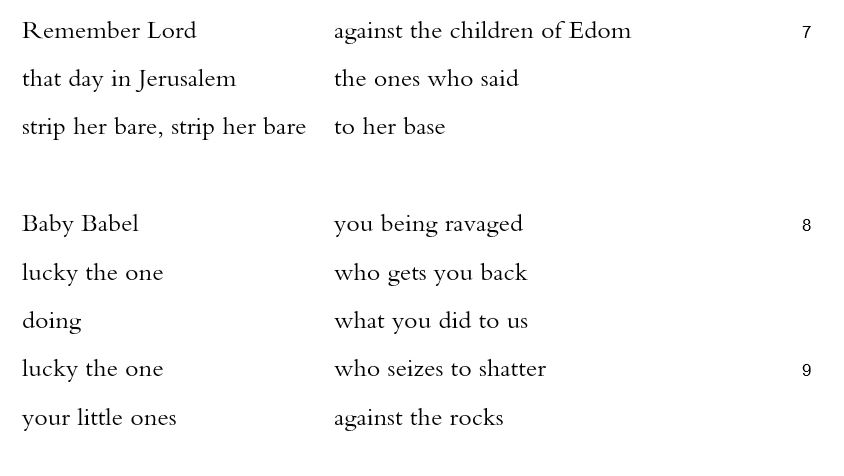

If verses 5 and 6 anticipate the future, verse 7 recalls the past, asking the Lord (and readers) to remember Edom’s role in razing and raping Jerusalem: “that day in Jerusalem | the ones who said / strip her bare, strip her bare | to her base.” The image is unmistakable in Hebrew, with `aru `aru `ad haysod bah meaning literally “expose, expose her down to the bottom” (see Job 4:19, Hab 3:13). It may be a metaphor for the destruction of the temple or the city walls, but its literal meaning is of stripping a woman naked.

Deeply and paradoxically auditory, the psalm is equally vividly visual. It presents speech and/or music in each of its first 7 verses, not to mention tears in verse 1 and the exclamations ki (3) and ’akh (4). The sounds are frequently forceful, from sham she’eilunu shoveinu… shir lanu mishir tsiyyon in verse 3, to ’et-yom yerushalayim ha’omerim `aru `aru `ad hayesod bah in verse 7, to the cluster of zakhar (to remember 1, 6, 7), naharot (rivers or waterways, “channels” 1), nekhar (strange, 4) that runs throughout. The music of the psalm is paradoxical, like Yeats’s “On Being Asked for a War Poem” or Hayden Carruth’s “On Being Asked to Write a Poem Against the War in Vietnam.” To the captors’ demand, the psalm protests, “Ah how can we sing,” a kind of continuity and rupture, a sure sign of the ineffable. And yet to express this ineffable, the psalm relies on primarily visual imagery, “let my right hand | forget how / let my tongue clutch | the roof of my mouth” (5). The profoundly ambivalent picture of harps “strung up” “on poplars” in verse 2, conveys both silence and the readying for music. And the most vivid image in Psalm 137 is the final one, grotesque in what it makes us see, and hear, and in its silence.

Against these horrors are the psalm’s care and poise, with repetitions, for example that are meaningful and perfectly timed. Babel and Babel frame the poem (1, 8), while Zion and Zion begin it (1, 3). The name of the Lord appears twice (4, 7), the word for gladness twice (here, “smile” in 3 and 6) along with two uses of “lucky” (8, 9), “sing” twice, “song” three times (3-6), Jerusalem three times (5, 6, 7), and three times the word “remember” (1, 6, 7). Twice the psalm reports foreign speech, of Edom (7) and of the captors (3), and three times the speaker’s “if” (5-6). The patterns are thorough contrasts: the two capitals and the measure-for-measure revenge implicit in the repeated “strip her bare” (7c), with a feminine ending that is picked up in the very next line by the word “daughter,” used of cities idiomatically in the Bible and rendered here as the diminutive “Baby” (8a).

Subtlest of all, so easily lost in translation, is the insistent `al that runs throughout the psalm, the preposition that means “towards” and “up” among many other things. It begins verse 1 and verse 2 and helps conclude verses 4 and 6: “Up the channels,” “Up the poplars” (whose name `aruvim anticipates, even triggers the `aru `aru memory of assault), “up a land | so strange,” and “up top of my smile.” It may sound awkward, the “up” of this particular translation. But it is a necessary part of the psalm, that repeated direction of awkward lifting up. In verse 6, the preposition becomes the verb “to go up,” `alah, where it is negated in the causative stem: “if I can’t lift up / Jerusalem.” The payoff of all this lifting up and up arrives in the psalm’s brutal closure, where `al is revealed to be just a fragment of the word for a young child, `olalayik, “your little ones” and the final preposition changes terribly from `al to ‘el, “against.”

Of course the ending is uncharitable, horrible, and cruel. Far worse is the pearl-clutching of prim readers who wish this psalm would have ended instead with the turning of a cheek. The right response to atrocity is not to want victims not to want justice, but to want war to end, full stop. And war only ends if we all stay with its scenes long enough, hearing and seeing the pain of the orphan and the widow’s grief and the righteous rage of mothers bereaved.