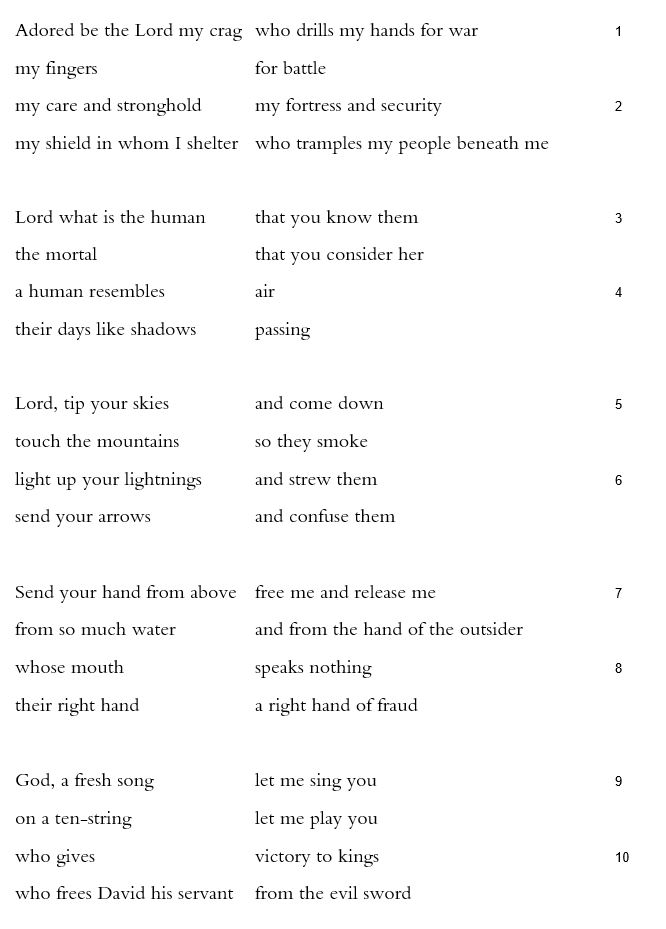

(of David)

* * *

Psalm 144 has as many jump cuts as a film montage or trailer. Splicing may be its most important technique: within verses, between verses, and between the first eleven verses with their mottle of quotations and the strikingly visionary poetry of the final four verses. To a greater degree than most other psalms, interpretation depends on whether we see the form as primarily chiastic, static, a series of frames around a center that makes sense of the whole, or as primarily narrative, dynamic, a sequence of moments that aims from beginning to end. Seen as a concentric structure, Psalm 144 seems like a code whose answer decoded is David, the former and wished-for king. Seen as a gradual unfolding, however, the psalm is more like a time-lapse series of stills, which revisits David’s psalms to revise and replace them, leaving behind a vision of freedom from the sword.

The middle of the psalm is marked by a refrain, a duplication that has often been dismissed as a copyist’s error:

Free me and release me | from the hand of the outsider

whose mouth | speaks nothing

their right hand | a right hand of fraud (11, cf. 7-8).

In verses 9 and 10, between these dangerous hands and worthless mouths, is the psalm’s center, with its implied hands and mouth of music:

God, a new song | let me sing you

on a ten-string | let me play you

who gives | victory to kings

who frees David his servant | from the evil sword (9-10).

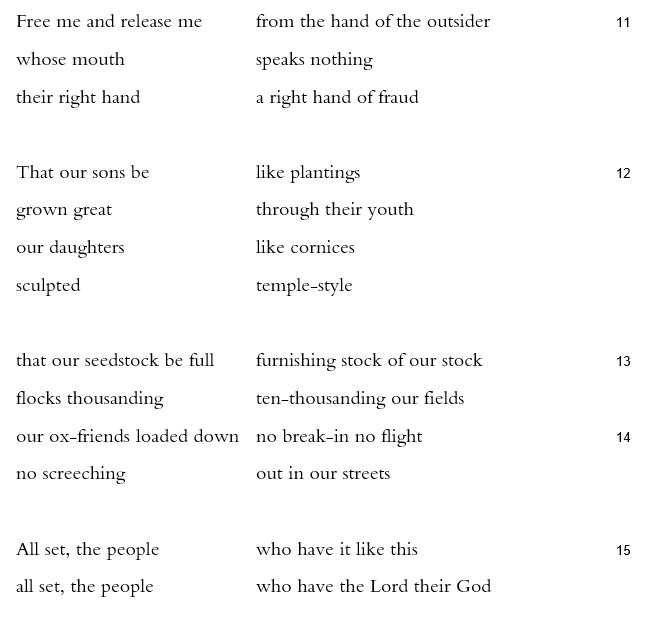

In that crucial verse 10, the participle happotseh, “who frees,” comes from the same root as the imperative petseini, “free me,” in the refrain in verses 7 and 11. These are the only three verses in the Hebrew Bible where the verb patsah, “to open,” takes on the sense of freeing, elsewhere always opening like a mouth. Framed in this way, the open mouth that sings a new song meets the dexterous fingers on the ten-string harp, both contrasting with the emptiness of the outsider’s hand and mouth.

A chiastic approach works less well for most of the rest of the psalm. The theophanic storms of verses 5 and 6 have little in common with the standing sons and daughters of verse 12, though both are vertical images, one full of wild motion, the other stillness. The wisdom theme of human evanescence in verses 3 and 4, if paired with the vision of fertility and flourishing in verses 13 and 14, lacks the kind of keyword repetition associated with tight textual frames. The beginning (1-2) and end (15) pit war against peace, but only in the broadest of ways.

In this broad way, however, the sequence of themes in the psalm’s first half seems to be matched and countered by the sequence in its second half. A prayer of preparation for war (1-2) relies on a vision of human life as “days like shadows | passing” (4), which in turn gives way to cosmic intervention (5-7). In the second half, prayers are not for war but for growth and stability (12); life is not futile, but fertile (13-14); instead of divine thunder, there is “no break-in no flight / no screeching | out in our streets” (14). The wisdom is not that all is air, but that the good life makes “all set, the people,” plural (15a, 15b).

If this kind of broad pattern sounds as familiar as many of the verses from the first half of Psalm 144, it is because both come directly from Psalm 18 (||2 Samuel 22). Psalm 18 is the powerful, old, martial psalm of David which also has two halves: God’s rage, then the king’s sword. It moves from divine lightning and archery (18:14, cf. 144:6) to the king’s own bending of a bow, his hands trained for war (18:34, cf. 144:1). Psalm 144 shrewdly reverses the order of that movement, beginning with a militarism that it adjusts, increasing David’s violence and decreasing God’s. It adds “my fingers for battle” (144:1) and changes “who tramples the peoples beneath me” (18:47) to “who tramples my people beneath me” (144:2) to quotations from David, but changes God’s appellation “my cliff” (18:2) to “my care” (144:2) and leaves out fiery coals (18:13).

The first half of Psalm 144 sews together other quotations from other psalms, to be sure, which is part of what makes it feel anthological or like a montage. But Psalm 18 is the one that matters most to Psalm 144, the psalm it quotes most, the psalm whose vision of a David trained for war it works so hard to reverse, to revise. David is made to sing a new song, in which God is celebrating for freeing “David his servant | from the evil sword” (10). This freeing makes possible the gorgeously wrought image of daughters “like cornices / sculpted | temple-style” (12).

Despite the uses to which this psalm has been put, this is not a resurrected David, let alone the return in triumph of a Davidic son: it is sons rooted and daughters stood true. Its vision of peace depends not on messianic eschatology but on the opening of a mouth to sing and on the opening of a hand once trained for war to drop its awful sword.