* * *

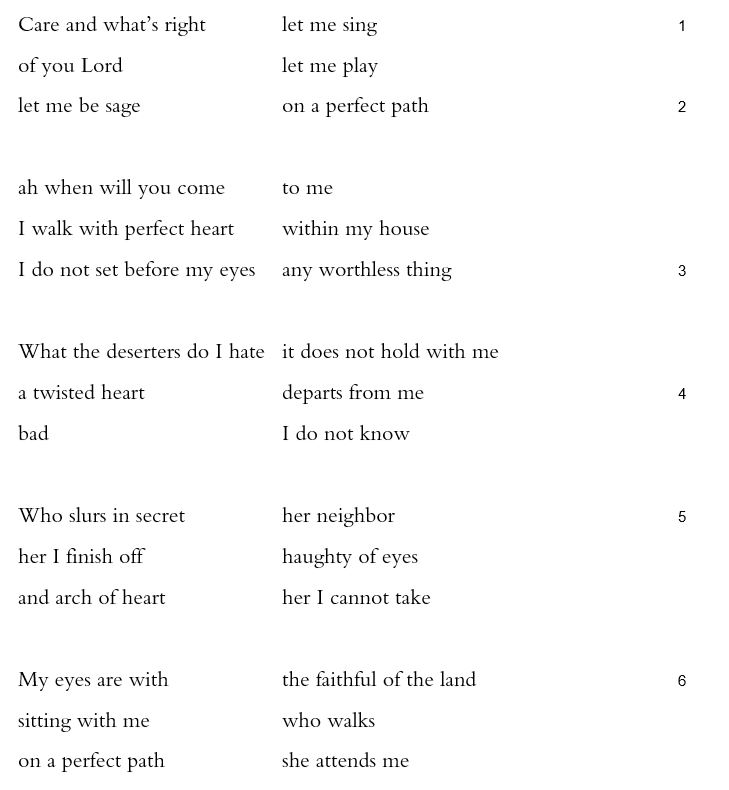

A striking collage of personal lament and Zion’s praise, Psalm 102 holds together powerfully if we hear the lament as spoken in Zion’s voice. “Lord | hear my prayer,” the psalm begins generically, in the voice of conventional address (1). In verses 3-11, however, clichés gradually fade. A tight five-stanza complaint follows, with images of fire and dry grass, smoke and shadow (3-4a, 10-11) surrounding images of bodily wasting, and forgotten or ashen bread (4b-5, 8b-9), all surrounding a remarkable trio of bird similes:

I look like a cormorant | in the wild

I’ve become like an owl | of a ruin I’ve kept watch

and am as a wren | alone on a roof all day (6-8a).

Solitary birds, perched or nestled on wilderness and ruin and roof, they linger night and day.

As a lament, the passage is more metaphorical than informative. The speaker suffers from loneliness, from emaciation and mourning, and from impending mortality, the spread of shadows and evanescence of days. Only in the last of these five stanzas does the speaker return to address God in the second person, revealing bitter hurt: “from your face of fury | and fuming / oh you lifted me | to throw me down”(10).

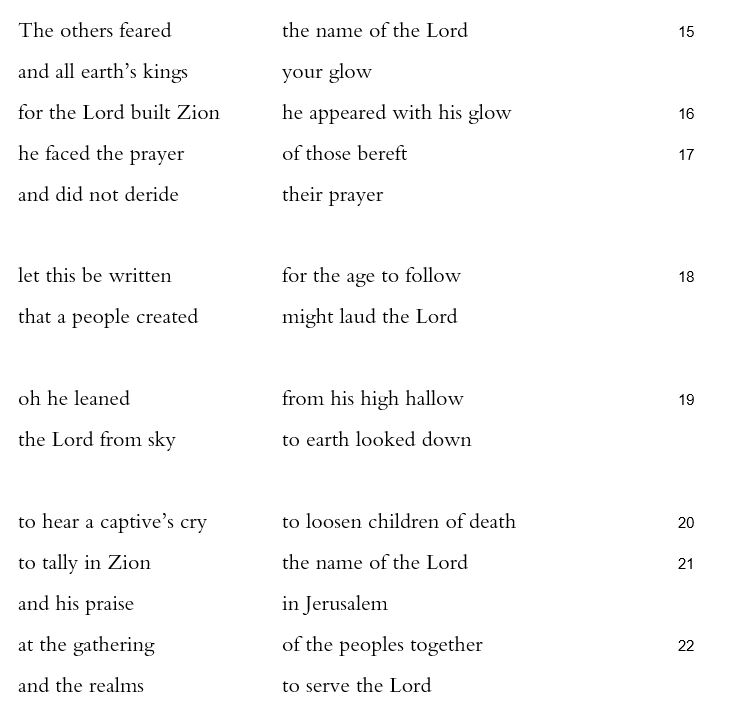

While this lament in verses 3-11 is prefaced by the formulaic verses 1-2, the broader memory of what Zion was in 15-22 has its own preface in verses 12-14. Instead of the past, it emphasizes both timelessness (“you Lord | ever stay” 12) and the transformative now (“oh the time to feel for her | oh the moment has come” 13). That the moment has come recalls the shout of the trees in Psalm 96:13, “oh he’s come he’s come,” ki va’. Poignantly, the announcement that the time has come for the Lord to pity or feel compassion for Zion is mirrored by, maybe even motivated by, the compassion that the Lord’s servants feel for her “ash” (14, cf. 9). Zion’s ash is the speaker’s ash, her ruins the speaker’s ruins. Verses 15-22 recall the building of Solomon’s Temple, when the Lord “faced the prayer | of those bereft / and did not deride | their prayer” (16-17). The passage also looks back to when “the Lord from sky | to earth looked down,” some past time, either construction or afterward, with a series of infinitive purposes:

to hear a captive’s cry | to loosen children of death

to tally in Zion | the name of the Lord

and his praise | in Jerusalem

at the gathering | of the peoples together

and the realms | to serve the Lord (20-22).

The Zion passage, then, pairs what the temple was with this vision of what the temple was meant to be, and still could be: a kind of listening post as Solomon describes it in 1 Kings 8. The hearing of the captive’s cry is both past and future, as is the loosing of children from the threat of death, that they might tally and serve. Cumulatively, the passage remembers a past in order to look forward to the present, and as it does, it creates a present that looks ahead: “let this be written | for the age to follow / that a people created | might laud the Lord” (18).

Both the lament and the Zion sections are vivid and affecting, each finishing with what feels like an end: the dried up grass of verse 11, all the kingdoms and people gathering in verse 22. The psalm’s final movement has to bring the first two together, to make the first section’s personal sense of the lengthening shadows of days meet the second section’s historical sense of Jerusalem’s loss and God’s timelessness. Now that we are in the moment of the psalm, the moment of compassion for Zion, the speaker suddenly cries, “He sapped my path of power | cut short my days / I said my God don’t | snatch me up with half my days / when age after ages | are your years” (24). Again the psalm returns to the past with a purpose: to show what does not change. The earth and “the skies / they end | but you go on” (25b-26, cf. 11-12). “All things age as clothes | as a coat you slough them off / they slough off | but you are the one / whose years | do not end” (26b-27).

Powerfully, a psalm with so much ash and rubble, so much loss against such changelessness, ends with an almost Rilkean image of descent and figures for eternity. “Your servants’ children | settle down” (28) is a continuity that shares God’s timelessness with ages to come, the readers implied by verse 18. This verb “settle down,” yishkonu, is echoed by its parallel verb “is set,” yikon, the very last word in the psalm. It’s the word used for a foundation, and what is being founded is “their seed,” the offspring, the line. What but a seed pressed into the ground could serve as such a potent response to the dried grass and bones and dust of Zion’s lament, compensating for loneliness and the cutting short of days? What better way “to loosen children of death” than to see children settling and seeding the ground?