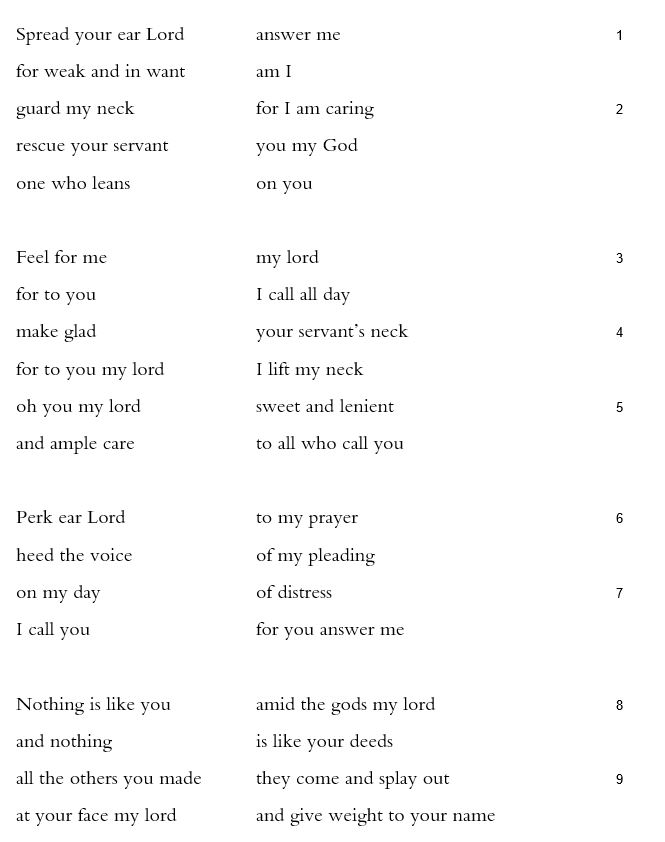

(a prayer, of David)

* * *

There is a striking gap between the expectations Psalm 86 comes bearing, given its location near the culmination of the central book of the Psalter (73-89), and its inescapable lack of quality. Framed by two pairs of Qorachite psalms, the only Book Three psalm designated by superscription as “of David,” the psalm ought to be particularly significant. Instead it’s blithe and generic, derivative and thin. When the speaker, a posturing monarch, claims to be “weak and in want,” he seems rather to be talking about the psalm itself (1).

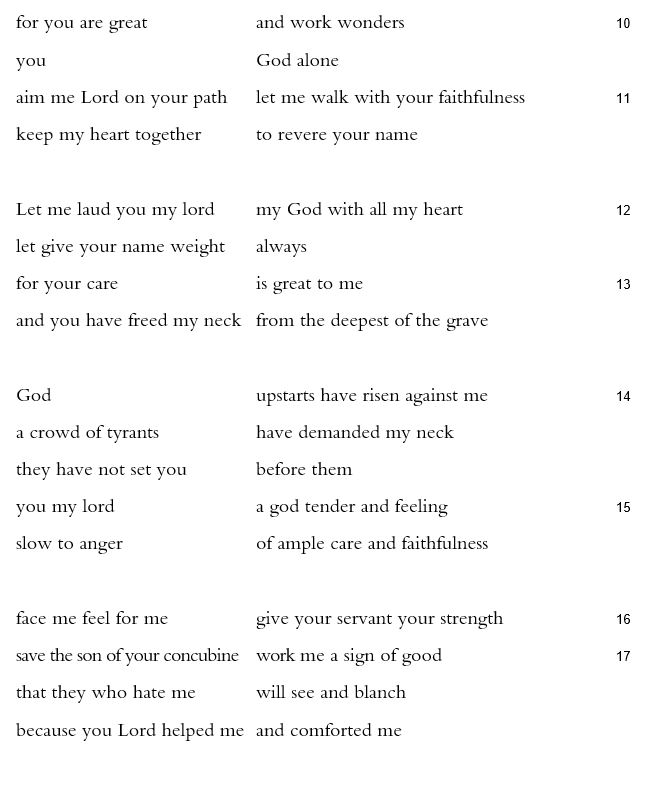

The threat that has led the speaker to call out to God in the first place is not clear until the psalm’s third movement: “upstarts have risen against me / a crowd of tyrants | have demanded my neck” (14). For our sympathies, everything depends upon who these rebels and ruffians are: foreign invaders demanding tribute? vassals asserting their independence? striking mineworkers? insurrectionists? syncretists? regicides?

For the first two-thirds of Psalm 86, not only do we not know who “they who hate me” are, we have trouble learning anything distinctive about the speaker. In the psalm’s first movement, the speaker beseeches favor and feeling without giving a reason. He wants God to answer (1, 6-7), to protect his neck and make it glad (2, 4), and to feel for him (3), but the only explanations are circular. He says, answer me (1) for I am calling you (3), for I am calling you because you answer (7). “Answer me/ for weak and in want | am I,” he also says, `aneni ki `ani ve’evyoni ’ani, making wordplay do the work of associating the first-person pronoun with the imperative to answer, linking the two by the claim of being destitute.

Nearly all of the first three stanzas is spent on repetitive, conventional gestures of deference and beseeching. The speaker is “your servant” (2, 4), represented here only by his throat (2, 4 x2, cf. 13, 14), which appeals to God (2) as Lord (1, 6) but more as “my lord” (3, 4, 5). Quotations and conventions abound in every verse, from the prayer of Hezekiah “Spread your ear Lord” (Ps 86:1, 2 Kgs 19:16; cf. Pss 31:2, 71:2, 88:2), to the phrases “weak and in want” (Pss 86:1, 40:17, Deut 24:14, Job 24:14, and more), “guard my neck” (Pss 86:2, 25:20), “for I am caring” (Ps 86:2, Jer 3:12), “feel for me” (Pss 86:3, 6:2, 31:9, and more), “to you | I call” (Pss 86:3, 28:1, 30:8), “to you my lord | I lift my neck” (Pss 86:4 = Ps 25:1, with the change from “Lord” to “my lord”), “ample care” (Ps 86:5, 15, Num 14:18, Joel 2:13), “perk ear… to my prayer” (Pss 86:6, 17:1, 55:1), “on my day | of distress” (Pss 86:7, 77:2), “I call you | for you answer me” (Pss 86:7, 17:6, with a change of verb form). It’s more pastiche than pathos.

The central section of the psalm, the most interesting part, is nevertheless still generic, still reliant on quotations, but now shot through with flattery. The “others” of the world are depicted in obsequious pose (9), as the speaker celebrates the glory (“weight,” 9, 12) of the Lord’s name (9, 11, 12) and whole categories of deeds and wonders (8, 10). Twice the word “great” is used (10-13). If one scanned the Deuteronomistic History for ceremonial prayers of kings from David (2 Sam 7:22 || Ps 86:8) and Solomon (1 Kgs 8:23 || Ps 86:8; 1 Kgs 8:39 || Ps 86:10) to Hezekiah (2 Kgs 19:15,19 || Ps 86:10), one might construct something similar. The very middle of the psalm, while it does rely on excerpts from other psalms—“aim me Lord on your path,” for example (86:11 = Ps 27:11)—ably links two lines about speaker’s heart (11, 12) while pairing “you alone” (86:10, cf. Ps 83:18, 2 Kgs 19:15,19) with the unique verb “unite” or “keep together” (Ps 86:11, cf. Ps 83:5). The Lord’s singularity and the speaker’s integrity resonate. It’s a nice moment.

Overall, however, the psalm is casual about its monarchical tendencies, even naïve. If a Davidic king is indeed in the circle of those who are weak and in want, swarmed by upstarts and tyrants, what must the rest of the people feel? To be clear, the problem is not that the psalm is conventional. Many psalms are traditional and many traffic in clichés, as do many prayers. The problem is that, even as a found poem or pastiche, the psalm feels empty. If, as seems likely, the psalm was written well after the collapse of the Israelite monarchy, during rule by foreign governors or occupying armies, nostalgia for home-rule must have been common and difficult to express without seeming seditious. It’s possible that a vaguely messianic prayer gave voice to subversive desires. Any subversiveness in Psalm 86, however, is lost by its vagueness, and by the insincerity of its first-person singular whose repeated use of “your servant” (2, 4, 16) barely disguises the speaker’s disregard for other people, or his will to power.