(didactic, an Asaph)

* * *

The destruction of places dedicated to Israel’s God is at the heart of Psalm 74. It is impossible to tell whether these special places are all part of one place, “Mount Zion | here you lodged” (2), Solomon’s Temple, razed in the 6th c. BCE by the Neo-Babylonians, or whether there were multiple places— “they set fire to all | the assemblies of God in the land” (8). It’s therefore also impossible to tell when exactly this psalm might have been composed or compiled, recited, or remembered, and whose needs it met first. But the date matters far less than the sense the psalm makes of catastrophe by retelling tragic collapse as an event that keeps coming to life. It flanks this retelling with appeals to even older foundation stories. And it frames all these narratives with unanswerable questions, less questions than outcries, and with a series of instructions for God, comprising eight imperative commands and four petitions slightly more polite.

The ruins commemorated and lamented in the psalm are what remains from intentional destruction by an enemy armed with flags, torches, and axes. The sequence of verses from 4 through 9 is concerned not with the slaughter of people, though there are “no more prophets” according to verse 9, but with the desecration of places: “your foes snarled | in the heart of your assemblies” (4), “they burned | your sanctuary to the ground / they hollowed | the tabernacle of your name” (7), “they set fire to all | the assemblies of God in the land” (8). Into these perfective verbs are set two verses that rely on imperfect forms, an effect that mirrors the English historical present: “and now her carvings | all together / with hatchet and hammer | they shatter” (6). That word “now” (`attah) works marvels, making timeless the moment of the destroying of figures carved to be timeless themselves, while also invoking by opposition its own near-homonym, “you” (’attah), used of God seven times in verses 12-17. The destruction is complete; its immediacy persists in a repeated now.

Against this panel of historical fact (4-9) is positioned a panel of prehistorical legend (12-17), the people’s memory followed by what should be God’s memory. The explicit second person sharpens the point. If anyone has the power to defeat enemies and lay foundations, it is you, God: “you broke | with your might the sea / crushed the dragons’ heads | on the waters” (13), “you ripped open | the spring and the stream / you dried up | rivers of lasting” (15), “you erected | all earth’s bounds / summer fruit and fall rain | you formed” (17). In the first narrative, God was the “you” in the object possessive: “your foes… your assemblies… your sanctuary… your name.” In this second account, God is primarily a subject, controlling verb after verb of action.

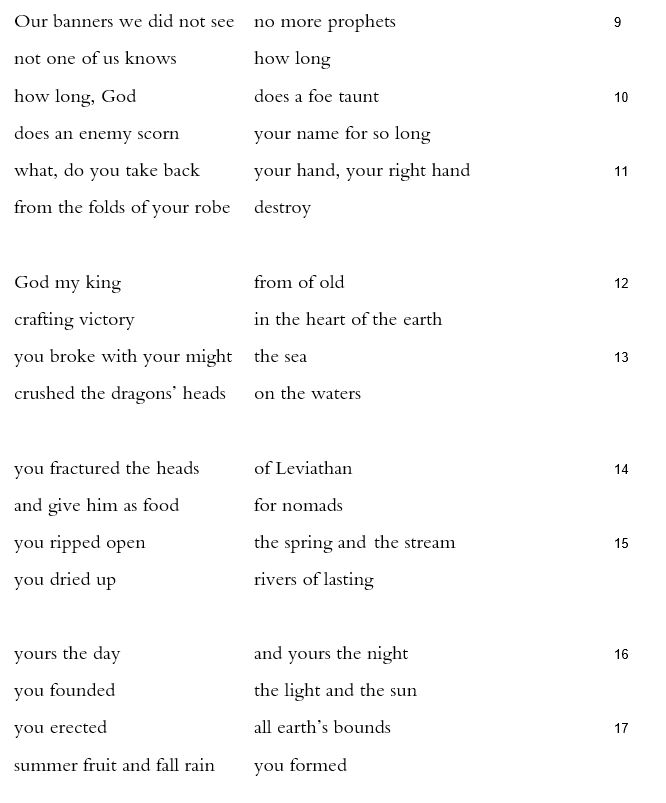

The first narrative is flanked by questions for God. The poem opens by pulling no punches: “What, God | have you been mad for so long | your nose fumes | at the flock of your field” (1). Both the interrogative lamah (what? why? how?) and lanetsach, the word rendered here as “for so long” return in verses 10 and 11:

how long, God | does a foe taunt

does an enemy scorn | your name for so long

what, do you take back | your hand, your right hand

from the heart of your chest | destroy

“How long?” The opening question has multiplied and become the psalmists’ cry. More, the passage reads like a stutter, especially when paired with the end of verse 9: “not one of us knows | how long / how long, God | does a foe taunt.” How curiously, how doubly, the question about God having taken away God’s hand becomes the imperative, “destroy.” The hand that has been inexplicably taken back into the folds of the robe retroactively becomes, through the final imperative, a hand being taken out from the folds of the robe.

The imperative kalleh, “destroy,” which was used notably in a different verbal stem in the previous psalm (kallah, in “my body ends” 73:26), is the third in a remarkable series of twelve orders that order Psalm 74. “Recall,” God is instructed three times (2, 18, 22). Most of the instructions are clustered at the psalm’s end, from verses 18-23: “recall… do not give some animal | the neck of your dove… do not forget for long (lanetsach) / Consider the pact… do not let the oppressed | return ashamed… Rise up God | plead your case / recall how the fool | taunts you all day / do not forget | the voice of your foes.” This burst of insistence blends appeals to memory with calls for action. The “Rise up” of verse 22 and “Recall” of verse 23 return to the opening imperatives, the “Recall” of verse 2 and “Lift her your footfalls” of verse 3. A poem that begins with God’s nostrils flaring and hinges on God’s hand has perhaps its most poignant moment in this image of God stepping up “to what’s been ruined so long,” yet another line that uses the word netsach, a word for what lasts.