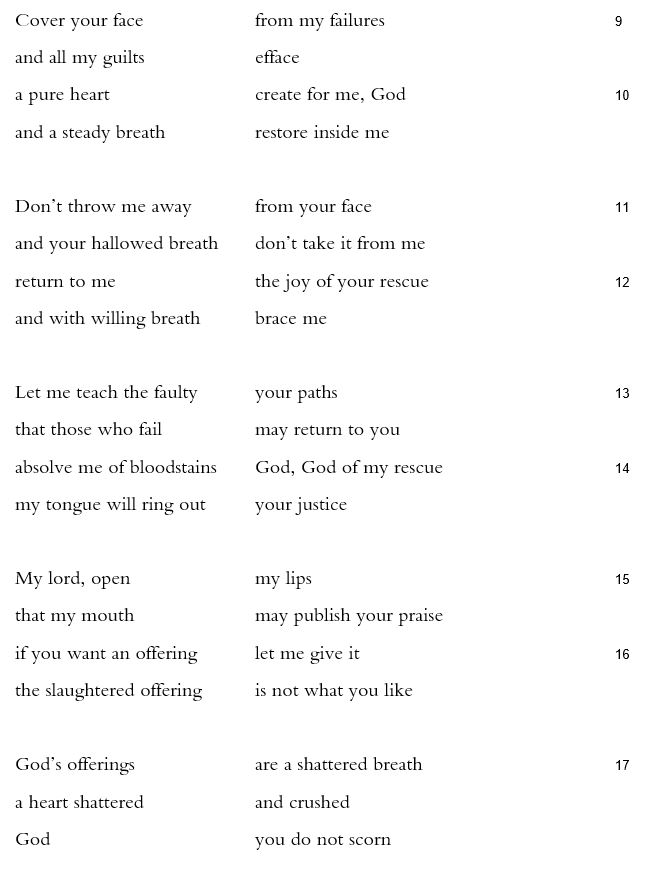

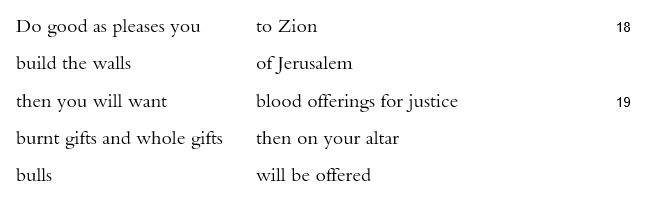

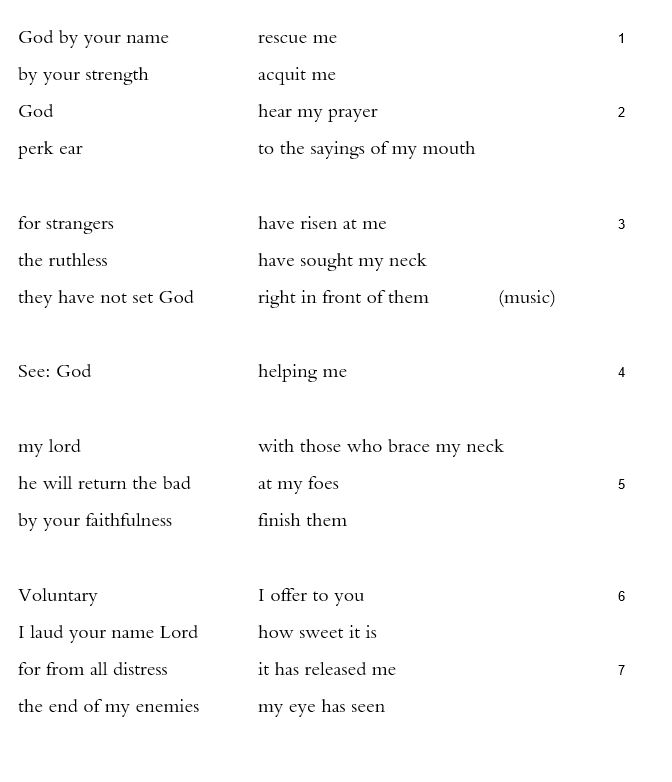

(director: with strings, instructive, David: when the Ziphites went to Saul and said, David is hiding with us)

* * *

Even a relatively straightforward text like Psalm 54, which is frankly unremarkable in English, can hide surprises.

First, there are compelling links between this psalm and Psalm 52. In 54:1, the root word for God’s “strength” is the same used twice in 52, there referring to the “strong man” (52:1,7). So when Psalm 54:1 begins with God’s “name” and strength as a pair of means by which God will “rescue” and “acquit,” the revisionary relationship with Psalm 52 is clear: there the strong man relied on power, confusing it with the name of God (by contrast with the speaker who said, “I hold out | for your name,” 52:9), here God’s name is paralleled with God’s strength. The focus here is not on God’s care.

A second surprise is this Psalm’s subtle balance and chiastic shape. The center of the poem captures an instant of transformation. “See: God | helping me” (4a) is a potent moment that works as its own clause with an implied “is” (or “is about to”). It also works by contrast with verse 3 (“they have not set God | right in front of them”). And it works in tandem with the rest of verse 4 as an introductory phrase for the main clause that arrives in verse 5:

See: God helping me

my lord with those who brace my neck

he will return the bad at my foes

That this moment is significant is clear with the next line, which introduces yet a third means by which God helps the speaker of Psalm 54: “by your faithfulness | finish them” (5b). We now have a triad of means for divine intervention, according to the psalm. God’s name, God’s strength, and God’s fidelity each has its work to do: the name rescues, the strength acquits, and the fidelity finishes off the enemies, as the final stanza (6-7) describes.

The satisfaction of the poem’s resolution in its final stanza comes not just from the speaker’s eye that witnesses payback. It comes as God’s personal name arrives in verse 6, YHWH, the Lord. And it comes in verse 6 from the sacrifice of thanks that is given freely, in rejoinder to the larger critique of sacrifices in recent psalms, Psalm 50, Psalm 51. Psalm 50 ended with a difficult line: “who offers thanks | honors me / and a name I will show | a path to God’s rescue” (50:23). The last stanza of Psalm 54 portrays both of those statements as accomplished: “I laud your name Lord | how sweet it is / for from all distress | it has released me” (6b-7a).