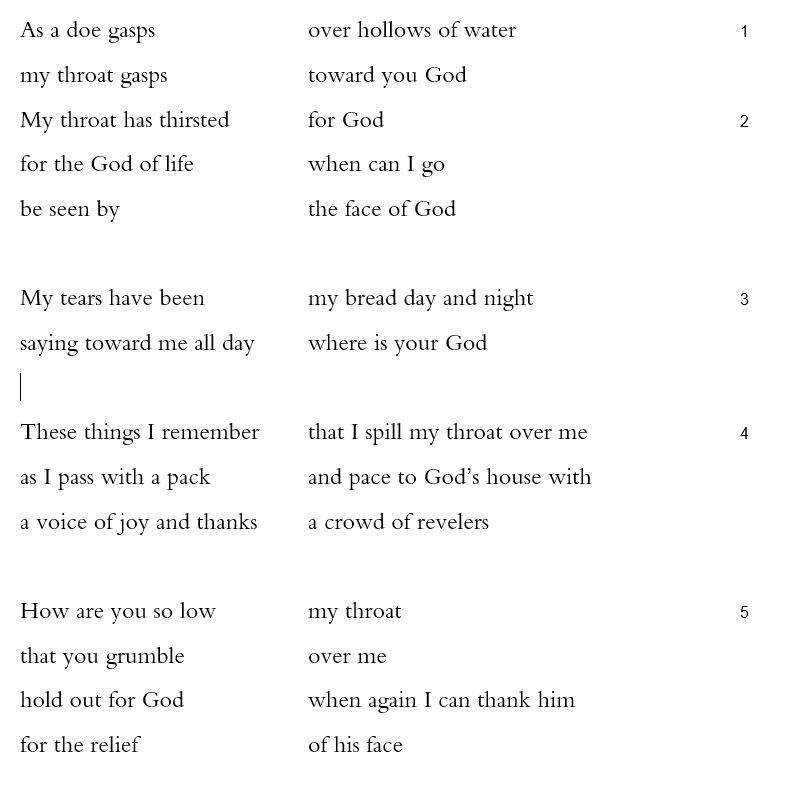

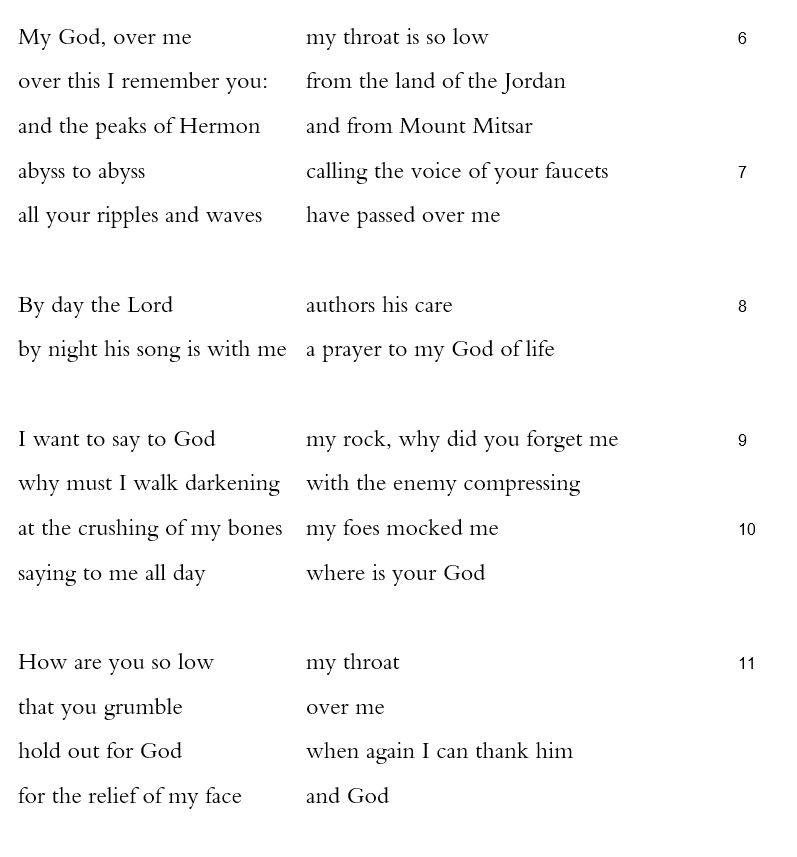

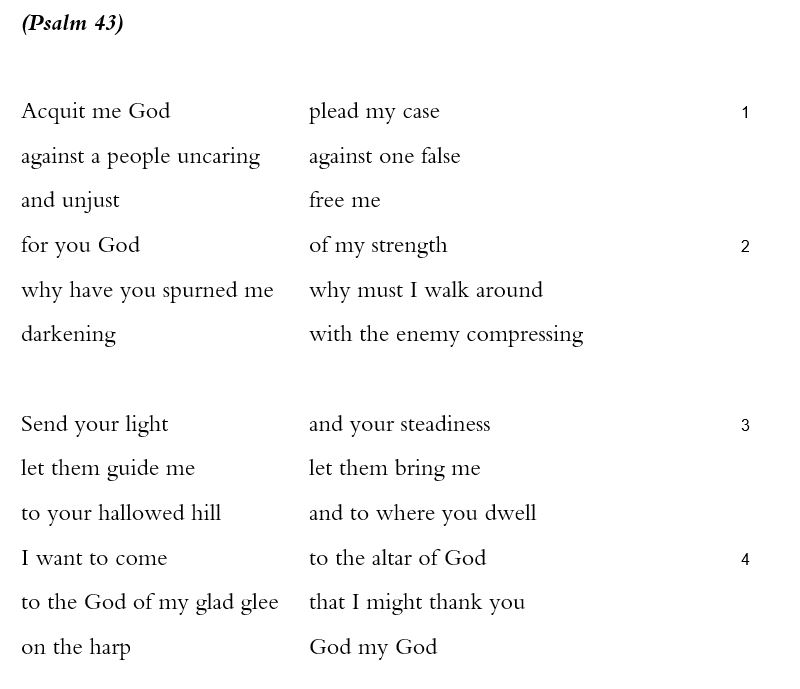

(director: Qorachites: song tuned high)

* * *

All the Qorachite psalms (Pss 42-49, 84-85, 87-88) are strong, structurally and musically. They rely on stanza-and-refrain patterns to help the psalm mean. There is the two-part structure of Psalm 45, king and bride, for instance, and there’s the three-part shape of Psalm 42/43 and of Psalm 44, which both move from the remembered desired to the far-from-ideal to a wished-for reconciliation. Psalm 46 ably manages to have both a two-part and three-part structure: two five-line stanzas (2-4a, 4b-6) surrounded by two two-line refrains (1, 7) against a third five-line stanzas (8-9), followed by a two-line envoi (or coda) (10) and a final two-line refrain (11). We move from an imagined flood that fails to harm the city of God (2-4a) to a flood remembered from within the city walls (4b-6) to wastelands at the country’s edge, at the end of the nation’s wars (8-9). In the refrains, God is “for us” (1), the Lord of Armies, the Lord of Forces, YHWH Sabaoth, is “with us” (7, 11), and a shelter (1) that becomes a fortress is “for us” (7, 11). Keeping the whole thing tight, God is named seven times, the Lord three.

Sonically, too, Psalm 46 is full of marvels. The first verse, the tongue on the gums, pairs `oz and `ezrah, “strength” and “help,” followed by betsarot nimtsah “in distress | … found.” In verses two and three, behamir, the infinitive that means transformation (“altering”), is picked up by harim (“hills”) and then in the “waters |clamor and lather,” yehemu yechmeru meimav and again by harim. The effect is to blend in sound what spill into each other in song, the hills and the seas. “Dwellings” (mishkenei) and “cheer” (yesammechu) play off each other in verse 4, and “who placed wastes” in verse 8 calls back those sibilants and m-sounds (asher sam shammot). Verse 9, however, is the real tour de force. The words “stopping” and “snaps” are mashbit and yeshabber, the words “edge” and “bow” and “cuts” are qetseh, qeshet, and veqitseits, but they’re even better in the context of the whole verse:

mashbit milchamot | `ad qetseh ha-aretz

qeshet yeshabber | veqitseits chanit

`agalot | yisrof ba’esh

Here the effect is also to blend sounds and sense, and to lend a kind of chiming inevitability to the ending of war.

As for the historical context of this psalm, that’s impossible to know for sure. The song’s message of patience in the face of external threats —“Let go and know | that I, God / rise over the others | rise over the land” (10)— accords well with Isaiah’s counsel during the Assyrian crisis. The combination of the “channels” in verse 4 and the “wastes in the land / stopping wars” makes for another compelling parallel, also in the 8th c. BCE, when Hezekiah’s workers kept water from Sennacherib’s armies in the Kidron Valley, tunneling that water to the Pool of Siloam, inside Jerusalem’s walls (2 Kgs 20:20). This evidence, however, is circumstantial, and any historical moment could be for the psalmist as much as matter of collective cultural memory as the drowning of Pharaoh’s army seems to be (6), as much as matter of mythmaking as the stories of creation and Noah’s flood.

Detached from its context, the psalm easily becomes nearly apocalyptic, with the inundation and desolation of the erets, that loaded word that means both “land” and “earth.” The easily detachable “Let go,” especially in translations that supply a copula between “I” and “God” to make the even more detachable “Be still and know that I am God,” sounds not just comforting but quietist (10). Together, these detachings make this psalm sound as if it suggests fiddling while Rome burns, chasing privatized peace while the earth dissolves and slides into the sea.

Just to be clear, that imperative to “let go and know | that I, God / rise over the others | rise over the land” is a plural imperative rather than a personal one. It has a political thrust in a time of war. The psalmist could not have foreseen rising sea levels on a global scale, for example, and nothing in the song implies or celebrates inaction in the face of that kind of siege.