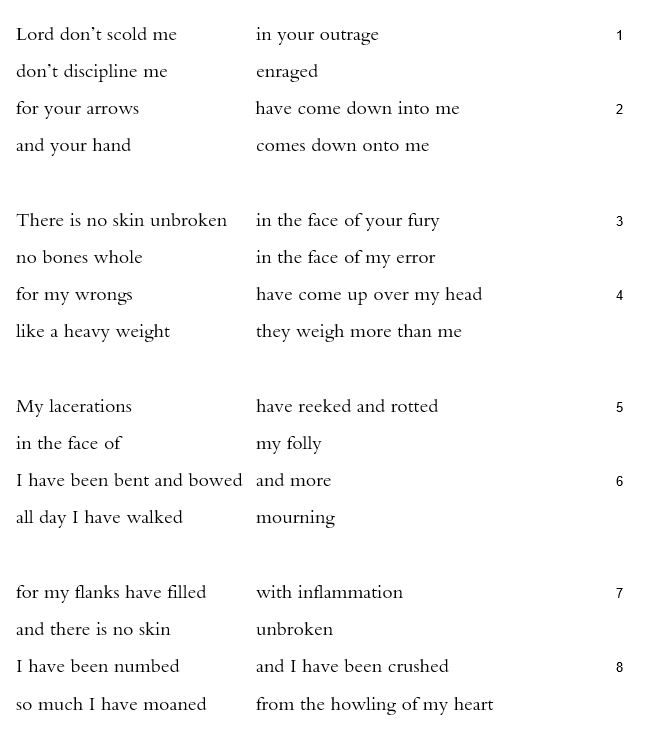

(director: lyric, of David)

* * *

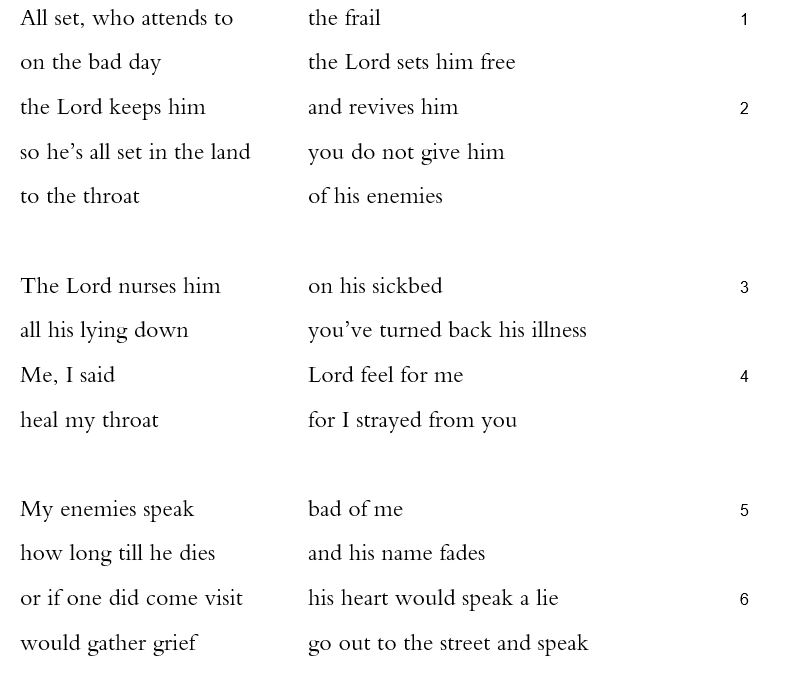

Psalm 41, the last psalm of the first section of Psalms, begins just as the first psalm did: ‘ashrei, “all set” (1:1, 41:1). Instead of simply opposing good and bad, however, the concluding psalm of this collection opposes sickness and health, good nursing of the sick versus terrible bedside manners.

The one who’s “all set,” blessed and happy both, is someone “who attends to | the frail” (1). This consideration for the weak aligns him with the Lord, who “nurses him | on his sickbed” (3). The repeated masculine pronouns blur the characters and types: the Lord, the sick one, the caregiver, and even, in verse 6, an enemy whose “heart would speak a lie” (6). The blurring amplifies the Lord’s role, divine care: “the Lord sets him free / the Lord keeps him | and revives him / so he’s all set in the land” (1-2). Who is this who is all set? “The frail” one? Or whoever looks after the frail one? By verse 3, all the blurring pays off, when the Lord’s own caring “on his sickbed” means healing the sick, present continuous, as well as healing, future tense, the one who has attended the sick.

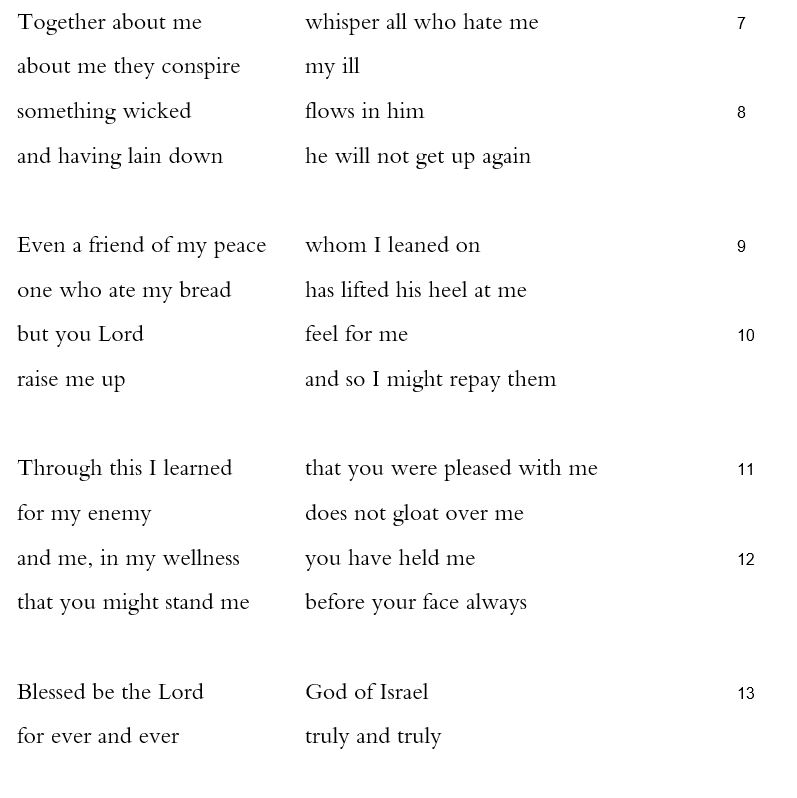

From its third-person overview, the psalm turns to first-person narration. It remains in first person for the rest of the psalm, verses 4-12. We learn that what makes the speaker’s enemies bad is not some immoral essence, but specific acts and failures. They “speak | bad of me” (5). They “speak a lie” beside the sickbed. And then they speak differently out in the streets (6), as they “whisper” and “conspire” (7).

Not even this speech of the enemies is simplistic. It starts by wondering “how long till he dies | and his name fades” (5). It ends with the wishful lie that “having lain down | he [the sick person] will not get up again” (8). But in between, in an imagined scene, the enemies’ speech transforms: “or if one did come visit | his heart would speak a lie / would gather grief” (6).

The syntax of that verse erupts with meaning. Does the heart speak? Does it gather grief? Does it do both? Or is it the visitor who gathers grief—or trouble—to himself, or does trouble gather him? Either way, this visitor with a deceptive heart heads to the streets and spreads lies: “something wicked | flows in him” (8). The line is a quotation, the liar publicly blaming the victim. But it works, too, as a characterization of the liar, one made even more incisive by the repeated use of the root word for speech in the word “something.”

Add to all of this slander the personal betrayal by a close friend, literally “a friend of my peace,” and the whole experience cuts deep. Verse 9 is particularly poignant: “one who ate my bread | has lifted his heel at me.” The lifting of a heel signals the actively passive act of walking away. It contrasts sharply with the Lord’s compassion and pity in verse 10: “feel for me / and raise me up | so that I might repay them.” The same word, shalom, marks both the friend and the root of the verb “repay.” It’s profoundly ambivalent: the repayment of peace for unkindness, the repayment of what’s deserved for unkindness. The peace that the friend of peace should have had—it comes back with a vengeance.

The final stanza, verses 11 and 12 (verse 13 is actually the benediction formula for each of the five collections of the book of Psalms), provides a fitting end for both the psalm and the first collection of psalms, Pss 1-41. The enemy no longer gloats. The Lord is pleased. And as for the speaker, “and me, in my wellness | you have held me / that you might stand me | before your face always.” Healing and reconciliation are achieved. There is a gesture of upholding, and of being-stood. All of these resolve both the specifics of this narrative and many themes of the first collection.