(didactic, of David when he was in the cave, a prayer)

* * *

The dual experience of a psalm of lament is to stand in two places at once. As we read, we are the petitioner, reciting and reliving, identifying with another’s cry we make our own. And yet as we listen, we are also the petitioned, overhearing, trying to understand that cry or help. To really hear a protest or wail, we listeners attend to at least three things at once: the pathos of the voice, what exactly it laments, and what we are supposed to do about it.

The particular voice of the speaker in Psalm 142 is marked in interesting ways as perfectly lucid, thoroughly traditional, and insistently self-aware, all features consistent with derivative, performative work. There are no textual complications or semantic confusions here, just linguistic clarity and syntactical precision (as, for example, in the preposition + infinitive constructions of the superscription, 3a, and 7b). The speaker doesn’t just call; she “pours” a “protest” (2a). The diction sounds similar to earlier psalms, often psalms of David. Verse 1 sounds like Psalm 30:8 and 77:1; verse 3 like Psalm 31:4. Manos, “shelter,” in verses 4 and 5 is also in Psalm 59:16 and 2 Samuel 22:3. “Pay attention to my shout” in verse 6a recalls similar expressions in Psalms 17:1 and 61:1; “free me from who harass me” in 6b echoes Psalm 31:15, and “they are too strong for me” quotes Psalm 18:17 exactly. From these similarities, from their sheer number, and, though this is wobbly logic, from the editorial position of the psalm near the end of the Psalter, these seem like quotations that have been adapted to be more emphatic than the originals.

The psalm’s self-awareness comes from its insistent use of the first-person. Psalm 142 begins and ends with the self. “My voice,” the first verse begins, then says again (1). The final line, the second half of verse 7, begins and ends with first-person prepositions bi and alai, “with me” and [to] “me.” Every line but 7b explicitly marks the first-person singular at least once. Every line through 5a marks it twice. The reflexive stem of the word for pity or feeling (or grace or charm) in verse 2 seems particularly rich. “I implore” means, in super-slow-motion, “I make myself pitiful.” So does the self-pitying statement in verse 6a: “oh I am so low” (6a). It can be a challenge to feel for people with such a sizeable head start on their own pity.

To sympathize, it helps to know what exactly is happening. The psalm offers few clues and many clichés. There is “crying out” (1a, 5a) and there is “distress” (2b), there are a “trap” (3b) and a lack of shelter (4a), present enemies (6b) and absent friends (4). All of these are common metaphors of complaint, generic enough to apply to any situation from embarrassment to assault. The most specific images in Psalm 142 are the catching of the breath (3) that has led some to assume the psalmist lay on a literal deathbed, and the “prison” (7) that has led others to characterize the speaker as either a literal prisoner, or a figurative inmate of an anachronistic hell. We could equally imagine the speaker as an exile or refugee (4), as a bullied child, a stranger, orphan, or widow (6), or as a temple priest, one whose only “share in the land” is the Lord (e.g., Num 18:20, Deut 14:27, 18:1), or as one of the indigenous opponents of Nehemiah (Neh 2:20). The voice is as easily that of a despot as is it of someone powerless.

The most concrete detail in the psalm comes in the superscription, which grounds this allusive lament in a narrative detail from the chronicles of David’s life: “when he was in the cave,” presumably the cave of Adullam, between the glories of his youth and his accession to the throne. Reading the psalm as David’s has a curious effect, limiting our ability to identify with the speaker, who as a figure of legend cannot be us, as well as limiting our ability to do much about that speaker’s distress. The psalm’s purpose becomes Davidic— to make sense of David’s loss of breath, David’s imprisonment. The location of this particular psalm, near the middle of the final cluster of psalms associated with David, Psalms 138-145, makes clear that a main project of the psalm is legacy work, what to do with a legend and a lost monarchy.

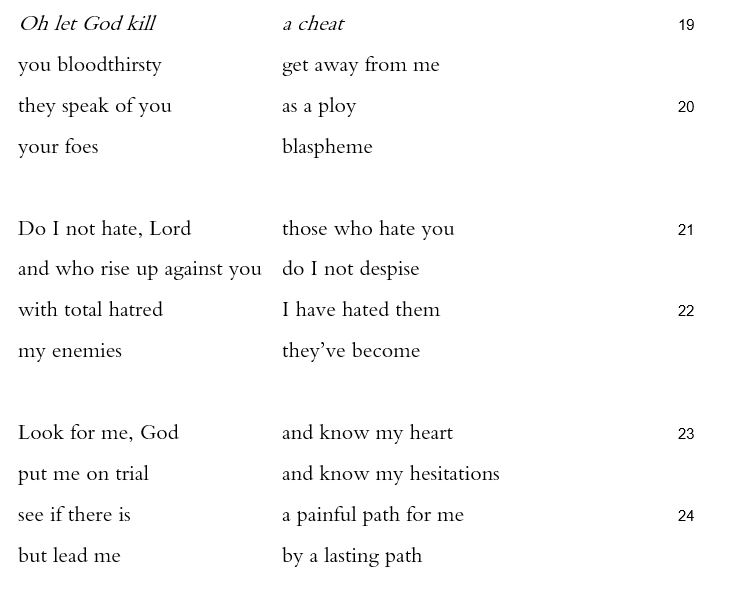

Everything depends, then, on the prepositions in the last verse. All of the quotations and allusions, the superscription, and its context at the end of the psalter make Psalm 142 about the departure of David in multiple ways. It’s David who, like a Levite, now has only the Lord as his share in the land, the land of the living (5). In verse 7, when David, buried in a cave, asks to be led out, his stated desire is “to give thanks | to your name” (7b), not to reclaim a throne. The last two lines, framed by the self-conscious “me” and “me,” reveal how David is to be led from prison, how his neck and breath are to be restored, “With me the just | circle around / oh you reward | me” (7c-d). The word bi, “with me,” can certainly be understood as the more messianic “to me,” which changes things dramatically, from circumference to spoke. But then, the phrase “you reward | me” can also be understood less positively as “you pay me back,” just deserts. The import of the last verse, however, even through these lively ambiguities, is to suggest a fitting fate for a king whose go-to poetic image was of being hemmed in by encircling foes. His compensatory liberation, here, is not to be crowned and worshipped. His voice, rather— “my voice,” “my voice” (1), “me,” “me” (7)— becomes part of the surrounding, the circle of devotees.