(of David)

* * *

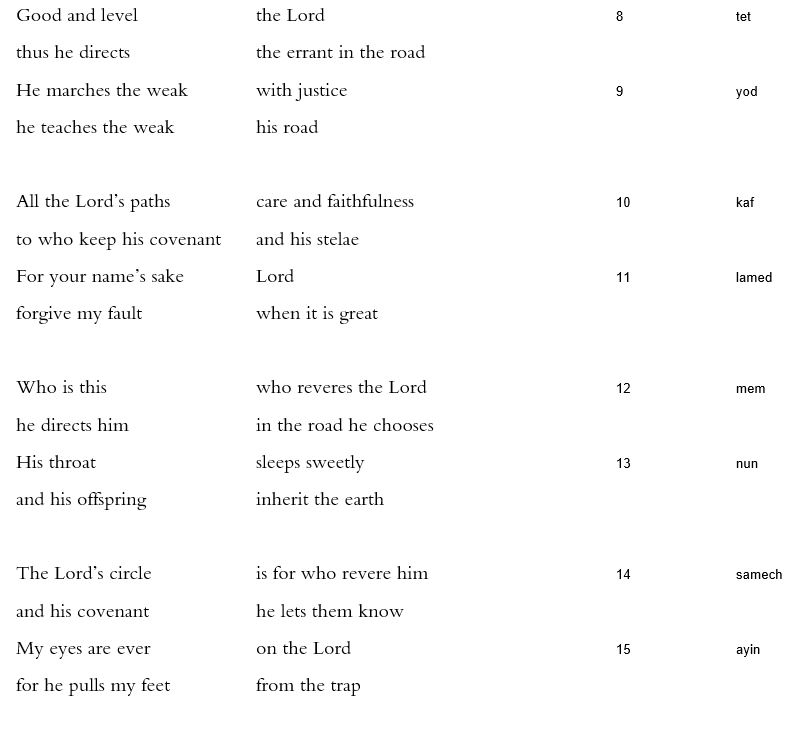

What is this? What holds it together? To call Psalm 25 an imperfect acrostic is to scratch the surface of its imperfections. As an acrostic, it lacks the letters bet, vav, and qof, but doubles the resh and adds a final peh. How did this happen? There are all kinds of possibilities, accidental through intentional, though without documents we rely on conjecture. One hypothesis that’s been suggested is that belated scribes failed to notice that their source material constituted an acrostic, and so shaped pieces of it into a new whole, discarding or disregarding some letters. This seems a stretch. Otherwise deft editors would suddenly miss the alphabet? And for the sake of this, which is not exactly a cohesive whole? Failure to notice makes less sense than some situation or intention or criterion of value about which we can only speculate, given the verses or parts of verses that seem to have gone missing. Any hypothesis makes less sense than the observation— forgive me— that this is in any case a middling psalm at best.

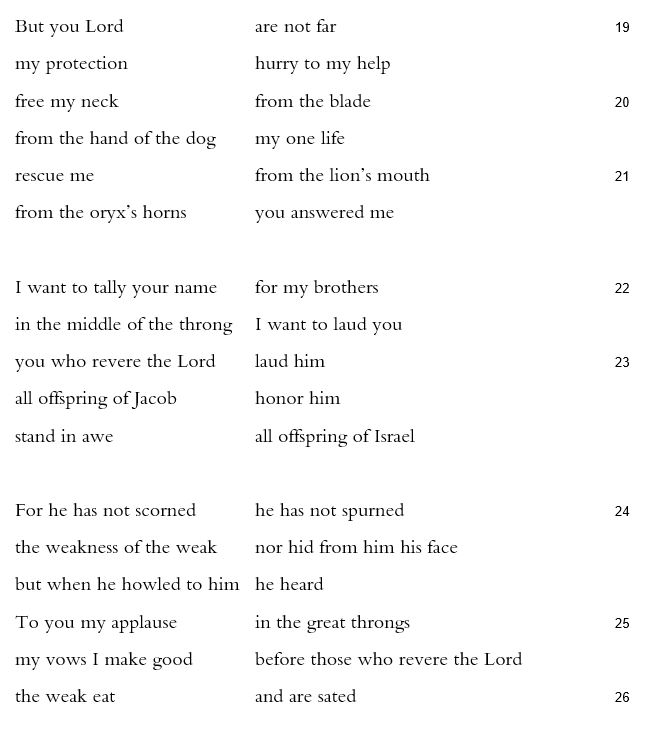

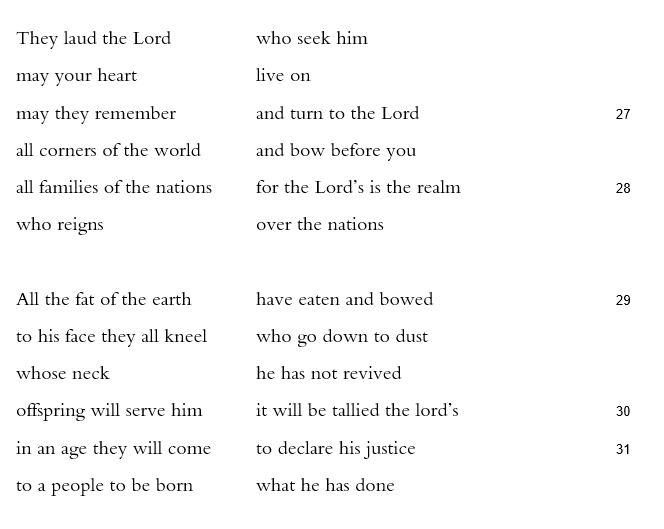

What is here? An introduction and conclusion pair a vulnerable throat (nafshi, 1, 20) expressing a wish not to be let down (or “ashamed,” al-aboshah, 1, al-abosh 20), having waited for help from God (“all holding on for you” 3, “I hold on for you” 21). Not clearly related, verses 4-5, 8-10, and 12, maybe 15, all depend upon the image of the road, with the Lord as a guide: “your paths | teach them to me” (4), “Good and straight | the Lord / thus he directs | the mistaken in the road”(8). To “learn the way” is a biblical figure for moral practice, made somewhat unique here by the doubled use of the denominal verb “to road,” translated as “to march,” in verses 5 and 9. Inside this cluster of verses are two verses that don’t refer to paths or walking at all. Verses 6 and 7 (which may have been preceded by a vav verse) ask the Lord to remember a relationship of love and to forget the speaker’s errors: “the mistakes of my youth |and my mutinies” (7).

The second half of the psalm is a touch more interesting, with theme-words that stitch cleverly across verses. It seems to center on “who is this,” the question in verse 12 that recalls the previous group of psalms, Psalms 15-24, while turning to the yirei Adonai, those “who revere the Lord”:

Who is this who reveres the Lord

he directs him in the road he chooses

His throat sleeps sweetly

and his offspring inherit the earth

The Lord’s circle is for who revere him

and his covenant he lets them know

Verses 12 and 13 pick up the image of the road from the psalm’s first half and the figure of the throat from the introduction, attaching them to the person “who reveres the Lord,” probably the convert who has joined from outside. Verse 14 makes this joining explicit, drawing the “circle” (sod, a council) and even the covenant around the singular, then plural, fearers-of-the-Lord. Verse 12 even presents a nice momentary ambiguity: who is it who chooses the road down which the Lord directs the one who reveres God?

But in verses 16-22, we don’t know what to make of the appeal for help from enemies and from heart-strain. The “weak” who were directed in the road in verse 9, we assume, return in the first-person in verses 16 and 18, just as the “mistakes” of verses 7 and 8 return in verse 18. But what does all of this imply? Having been taught the road, having been remembered, having been included in the circle of the Lord, how is the speaker now alone? There is a generic squeezing in verses 17 and 22, “pressures.” Is this experience of stress why the speaker feels let down?

But maybe these are the wrong questions. It’s an acrostic, after all, which means perhaps we should not expect cohesion. Maybe we should not feel let down by mostly conventional language and imagery.

*

25:2 let me not blanch Like the verb chafer, with which it is often paired in the book of Psalms (cf. 35:4, 40:14, the verb bosh seems to refer to the physical manifestation of embarrassment. Circulation can run hot or cold, as blood floods an area of the face (“blush,” chafer) or leaves it pale (“blanch,” bosh). This may be wild speculation—poetic logic.

25:3 let them blanch | who cloak for no reason The word habbogdim (“they who deceive” or “who cloak”) comes from the root bagad, whose core image is of clothing (beged) as concealment.

25:8 thus he directs Here the image is rich and clear: the Lord is “good and level,” and can therefore guide those who swerve from the road. This course correction is not punishment, but follows from both the Lord’s kindness and/or morality (“good”) and the Lord’s position and/or example (“level”).

25:10 and his stelae See note to Psalm 19:7

25:12 Who is this See introduction to Psalm 25 and note to Psalm 24:8

25:12 he directs him | in the road he chooses Biblical Hebrew’s habit of ambiguous pronoun reference, irksome to grammarians, is best preserved. The right and responsibility of puzzling through who directs whom according to whose choice is delegated to the reader.

25:13 sleeps sweetly The verse is sometimes interpreted to refer to material comfort that follows the one “who reveres the Lord” (verse 12). But the line very literally says “his throat with good lodges.” “Prosperity,” the word chosen by both the NIV and the JPS translations, opts for a very narrow segment of the semantic range of tov, which indicates all kinds of goodness. The NIV just does what it feels like here, discarding the Hebrew: “They will spend their days in prosperity…” The verse emphasizes not days but nights, actually, with the verb talin, to spend the night. People sleep well with good consciences, not piles of cash.

25:17 The pressures… from my constrictions One of the strongest verses in the psalm, the tsade verse pairs two images of deliverance as a release from squeezing pressures: the first release is a widening, the second an extrication.

25:22 Ransom, God A second peh verse (see 16) appears at the end of the psalm, out of alphabetical order. Because this verse asks for God to buy back Israel from its strictures, shifting from the first-person singular, perhaps it makes more sense here than it would after or in place of verse 16?