(director: lyric, of David)

* * *

Some meanings hang on a syllable.

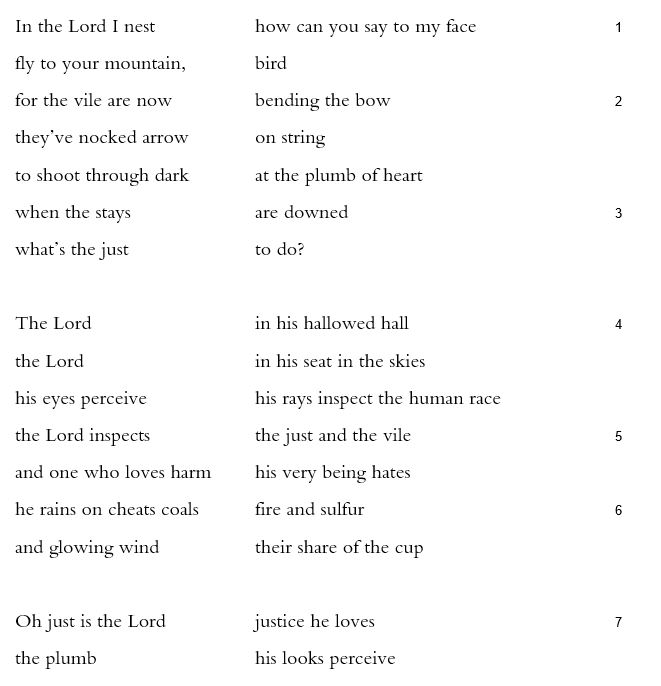

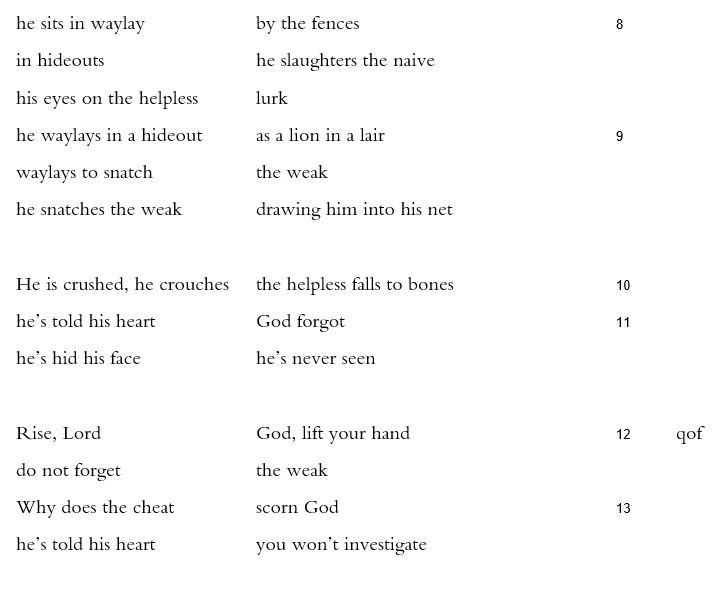

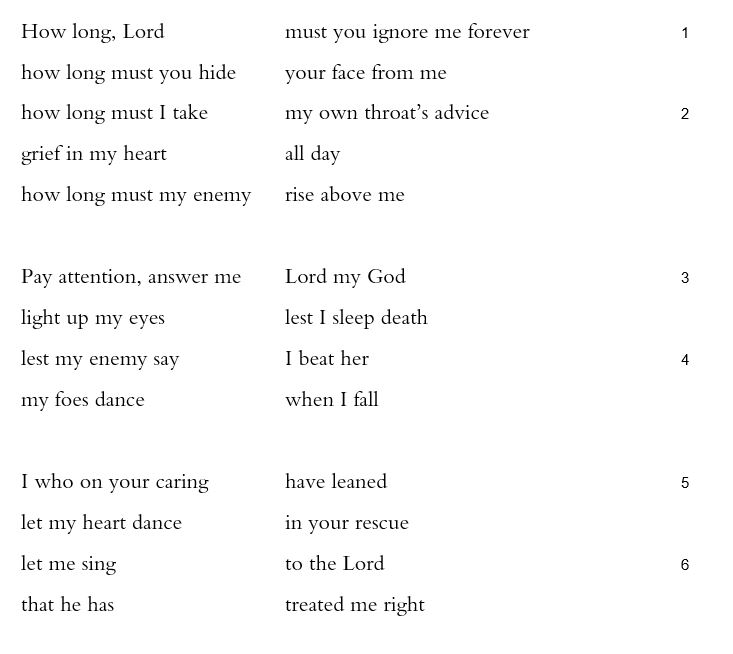

For five and a half verses, the anger and fear of this psalm’s plaint are perfectly clear. Aching and lonely from the outset, the speaker cries how long? Four times in two verses, she cries. Three urgent imperatives follow— “Pay attention, answer me… light up my eyes”—followed by three unwanted consequences: “lest I sleep death” (3b), “lest my enemy say | I beat her” (4a), and “my foes dance” (4b). The movement of both outcry and argument goes twice from God to the speaker to the enemy. “How long?” is asked twice about God (1a, 1b), once about the speaker (2a-b), and once about her enemy (2c). The imperatives follow a similar causal chain, from “Lord my God” (3a) to “lest I” (3b) to “lest my enemy… my foes” (4a, 4b). After these two verse pairs (1-2 and 3-4), the final pair softens to a plea as third-person wish becomes first-person: “let my heart dance… let me sing” (5b, 6a).

Those two imperfect-form verbs, expressing desire, are surrounded in the final verses by two other verbs, both in the perfect form, showing completed action: “I… have leaned… he has | treated me right” (5a, 6b). The meaning of this verb sequence is three-quarters clear: “since I have trusted you, I’d like my heart to dance and I’d like to sing.” The final verb, gamal, followed by alai means “he has dealt well with me,” “he has rewarded me,” “he has paid me back.”

But the rub, the kicker, the single syllable on which the psalm depends, is the word that introduces the final clause: ki, a conjunction with startling range. Two of its most important meanings are “for” or “because,” showing causality, and “when” or “if,” though this use is somewhat rarer with the perfect verb form. Thus it is possible to read the last verse to say either “I will sing to the Lord if he has treated me well” or “let me sing to the Lord because he has treated me well.”

The challenge is to render in one English translation the two strikingly different readings that the line—and thus the psalm it concludes—allows. Either the speaker’s wishes have suddenly come true off-stage, in which case the genuine anger and fear of most of the psalm have been erased in too swift a consolation. Or the patient movement of the psalm from “how long” to “answer me” to “let it be my heart [not my foes’] that dances in your rescue” has one final step, a wish in an imagined past-perfect tense: “I want to sing… once he has rewarded me.” Since we cannot have both “because he has | treated me right” (as most versions express) and “when he has | treated me right” (as only the NET Bible has, though this reading feels more honest), “that he has | treated me right” seems both literally accurate and appropriately open-ended.

*

13:2 my own throat’s advice Lit. the counsel of my neck. With the Lord’s face hidden, the speaker has to consult herself, turning inward from neck to heart.

13:3 lest I sleep death Lit. “lest I sleep the death.” The image is potent, and the King James is idiomatic and lovely: “sleep the sleep of death,” far superior to the NIV’s “sleep in death.” The sudden strangeness of the object is important to capture.

13:4 I beat her Lit. I beat him. Every gender deserves favor.

13:6 that he has | treated me right See the introduction to this psalm for a discussion on this verse. Alter comments wisely on this verse: “perhaps the prayer itself served as a vehicle of transformation from acute distress to trust.”