(of David, lyric)

* * *

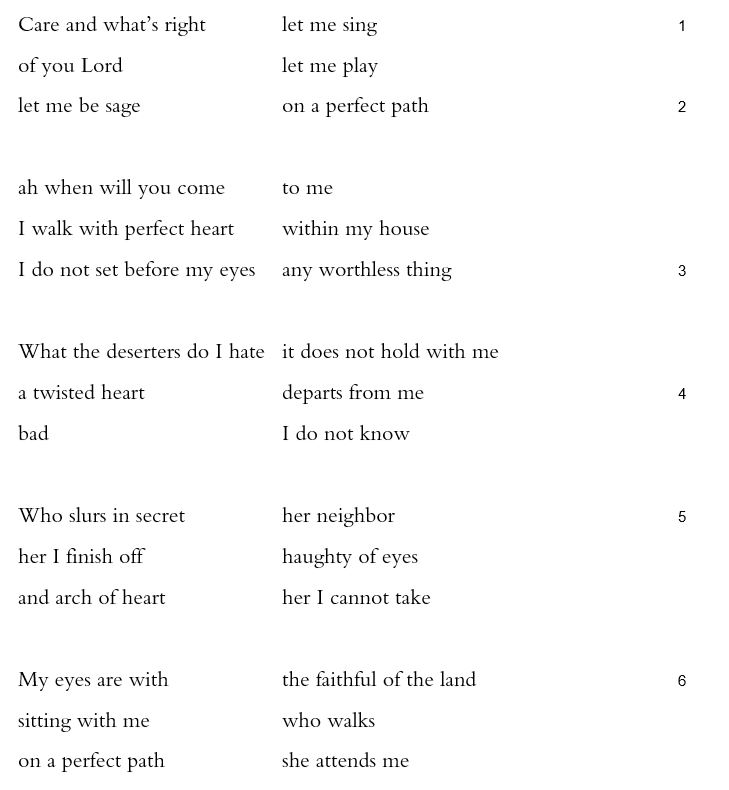

It’s not quite Arma virumque cano, but Psalm 101 does start by announcing its theme. It isn’t Virgil’s “arms and the man” the psalmist sings, but the ethical pair of chesed and mishpat, the divine relationship between loyal caring and legal rectitude, virtue and propriety brought together. That phrase “Care and what’s right” works both as a balanced pair and as a hendiadys, “right care.” It also squints syntactically with “lyric” in the superscription, “lyric of care and what’s right,” allowing the lyrics themselves to also begin with the more traditional “let me sing” (1; Exod 15:1, Isa 5:1, Ps 13:6). And yet Psalm 89—the psalm that precedes the collection of Psalms 90-100 which precedes this one, the most recent psalm to mention David—begins similarly, “The caring of the Lord | ever I sing (89:1). That verbal similarity suggests a different reading, linking “Care and what’s right” with “of you,” the lekha of the second line. It’s the Lord’s caring and virtue the psalmist sings and plays.

In the bulk of the psalm, at least in verses 3-8, this relational virtue or caring principle— or perhaps principled caring, virtuous relationship?— is demonstrated by a series of character types and the speaker’s relative distance from each:

There cannot sit | within my house

a worker of fraud | a teller of lies

is not sturdy | before my eyes (7).

Here, for example, are two categories of deceiver, plus two building metaphors. The one who plays false is an unwelcome guest; the one who speaks false lacks a foundation. With both, the crucial rhetorical move is not just to name the types, but for the speaker to pronounce her distance from them. The third stanza witnesses “deserters,” whose collective deed (“what the deserters do”) the speaker despises. “It does not hold with me,” the speaker says, adding in progression, “a twisted heart | departs from me / bad | I do not know” (3b-4). One could map this morality, location and vector, as those who cannot come towards me, and those who must go away “from me.” In verse 6, admittedly a curious place, are the good ones, the nearest of all:

My eyes are with | the faithful of the land

sitting with me | who walks

on a perfect path | she attends me

The faithful sit “with me.” The walker along the ideal way, she ministers to me. Motion or stillness, what matters is how close the speaker keeps these various character types.

Similarly, proximity is what’s at stake in the repeated mention of “eyes.” The psalm’s first and last expressions, “before my eyes,” are both negations. With both “I do not set before my eyes | any worthless thing” (3) and “a teller of lies / is not sturdy | before my eyes” (7), the speaker distances and purges. The two middle expressions contrast the boastful, “haughty of eyes / and arch of heart” (5), with the speaker herself, “my eyes are with | the faithful,” literally “my eyes with the faithful” (6).

But whose eyes are these? Who speaks in this psalm? Some assume a Davidic king speaks, given the superscription and the word “house” (2, 7). But nothing in the psalm itself makes the speaker a king. How could a king know “Who slurs in secret | her neighbor” or how, with any justice, declare “her I finish off” (5)? Does a king make nighttime rounds and “By dawn… finish off | every rogue of the land” (8)? Is that the same as “care and what’s right” or being “on a perfect path” (2,6)? After verse 2, the more likely voice is God’s, the Second Temple a more likely house than a royal palace.

The psalm thus means on at least two levels. We hear God—whom the last psalms have made clear IS the king—declaring values and rightness, orienting everyone in relation to God: “I walk with perfect heart | within my house / I do not set before my eyes | any worthless thing” (2c-3a). We also hear the human speaker, lingering past the first verse, justifying her own morality by her distance from others.

At the moment of transition, between the three opening wishes set clearly in the psalmist’s voice (“let me sing… let me play / let me be sage”) and the long list of declarations from “I walk with perfect heart” (2c) to “By dawn I finish off” (8) comes the psalm’s strangest, loveliest line, indeed probably its only lovely line: “ah when will you come | to me” (2b). That the consonants of “to me” (’elai) look like the consonants of “my God” (’eli) only amplifies the line’s curiosity. Who is asking whom? Is the speaker asking God, or God asking the speaker? How does this yearning for closeness relate to the finishing off and cutting off of enemies? Is the rest of the psalm one long attempt of a speaker focused on relationship to justify herself to a God she feels needs something proved?