(lyric, of David)

* * *

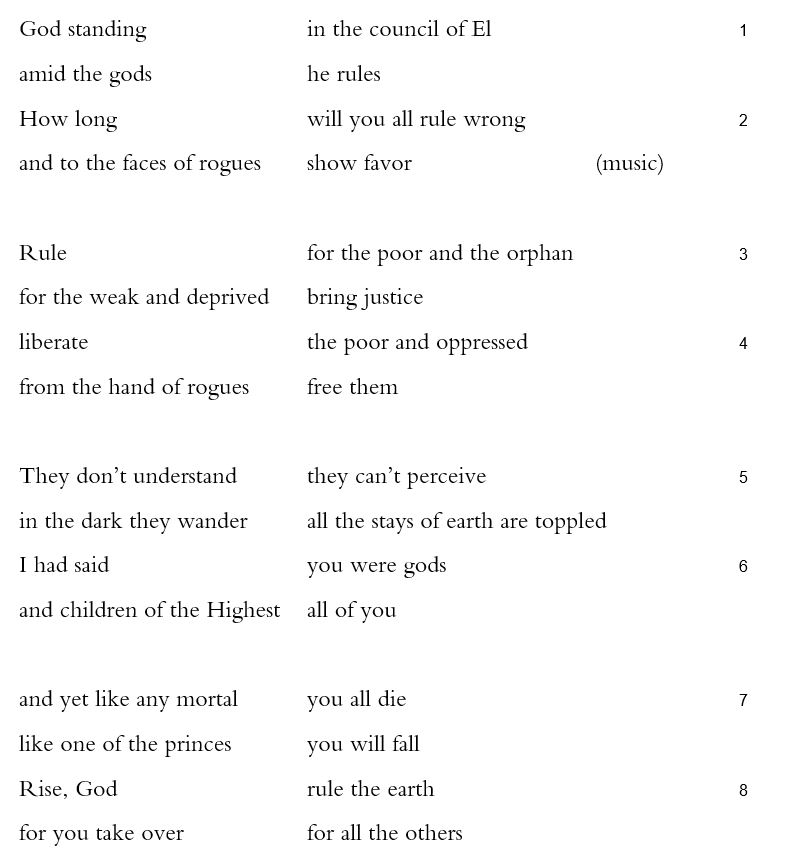

Psalm 143 is a valuable reminder that defining reason and emotion in mutual opposition— a common practice in popular understandings of poetry, music, scriptural traditions, and whatever we mean when we say “religion”— has no basis in either the body or the Bible, whose texts and cultures did not think, or feel, that way.

Each of the six ki-clauses in this psalm, for example, marks a logical turn in an argument even as it aches: “do not take to trial | your servant,” and why? Because “before your face | no one alive is just” (2). The word ki works as “because” or “if” or “when,” but it always means “oh”: “Make me hear at dawn | your care / oh I lean on you” (8). The particularly poignant verse 10 thinks as linearly as a geometry proof even as it moves with the associative logic of deep feeling: “teach me | to do what you want / oh you my God | your breath is sweet.” Even the meticulous verse 4, which relies not on a conjunctive exclamation but on two reflexive verbs, two prepositions with first-person suffixes, and two metonymical first-person subjects, hurts: “so that my breath | catches inside me / within me my heart | destroys itself.” Both breath (ruach) and heart (leb) figure life, then as now, in ways that obviate any separation of thought and feeling.

Figuring life is what Psalm 143 does. It’s a profoundly moving and richly theological poem that explores, more exactly, life-in-death. There is the one heart undoing itself (4), and the breath that falters just as it did in Psalm 142 (143:4 || 142:3), but “breath” recurs twice more. “My breath has vanished,” the speaker says in verse 7, moving from the ambiguous tense of the vav-construction in verse 4 (“so that my breath | catches” could equally well be “my breath | caught”) to a perfect-form verb. The final breath in the psalm is not the speaker’s, but God’s, the object of longing: “your breath is sweet” (10). Like “breath,” the word “life” appears three times in narrative logic in Psalm 143, first to mean everyone (kol-chai, negated by the verbal adjective l’o to “no one alive,” 2), then the life the speaker is losing or has lost (“ground to the ground | my life,” 3), and finally the life the speaker wants to hold to (“Lord give me life,” 11).

Even more pronounced is the fivefold repetition of the word nafshi translated here as “my throat” (3, 6, 8, 11, 12). Because the psalm is likely a late composition despite its superscription (it quotes other passages extensively; it’s positioned late in the book of Psalms), it is tempting to render nefesh by its later, top-heavy, abstract, Hellenistic, rabbinical, Jewish and Christian and Muslim senses of “soul” or “self” or “essence.” But its importance here is thought and felt so bodily. The speaker craves the Lord’s ear (1) and face (2, 7) and hands (5) and breath (10). Their own body is seated (4), then sinking (7), then walking somewhere they do not know (8). Their heart and breath wreck them (4), their hands have spread wide (6). “Throat” has range without baggage: it’s the body part most vulnerable to enemies (3) and to damage from crying out and thirst (6), the part of the body that lifts in song or gasps for air (8), that needs to breathe (11,12). The psalm is not remotely interested in some detachable essence.

It is, however, passionately reflective about the knife-edge between life and death and what that edge means. “Knife-edge” is not the exact term for this psalm, however. Life and death are separated, rather, by breathing (4, 7, 10), by hearing (1, 7, 8), by being visible as opposed to hidden (3, 7, 9), and they are separated by the horizontal boundary of the soil, the “ground” (3, 6, 10). The word “ground” works best for ’erets in this psalm, indicating the physical location of bodies that die, but it loses (can you hear me sigh?) the culturally specific and universally resonant implications of the term. The psalm’s most abstract theological reflection about the meaning of death and dying takes place in its opening and closing verses, where appeals to “your justice” (1, 11) are paired first with “your fidelity” (1), then with “your care” (12). In each case, these traits are instrumental, objects of the prefixed preposition b-, as in the awkward line “with your fidelity | answer me / with your justice” (1). The verse length and syntax are strange, but their felt thought is even more curious. If the causality is complex—that is, “because you are faithful, answer me justly”—how sincerely are we to take the pleading? Is the speaker asking for loyalty and justice, but justice without a trial, justice that is not typical justice? Are life and death just? Is it loyalty or fairness or lovingkindness that should make the Lord “end my enemies / and finish off | all who distress my throat” (12) or give life to the dead or dying (11)? Why should the Lord make those die and these live? These are good questions.

The afterlife of Psalm 143 may be as much a consequence of its unsolved (unsolvable?) questions as of its audiences’ concerns. To generations of sects and parties interested in the return of a Davidic king or other anointed one, the psalm’s working-through of the desire for revivification must have seemed relevant and potent. Verse 2 is alluded to by the authors of the gospels, where Mark’s Jesus declares, “no one is good if not God alone” (Mk 10:18, cf. Lk 18:19), and the Jesus of Matthew and Luke prays, “do not lead us to trial” (Mt 6:13, Lk 11:4). Together with verse 1, the opening of Psalm 143 is explicitly and elaborately retooled by Paul in Galatians (2:16, 3:11, and throughout) and in Romans 3, in interpretive passages that locate claims about the instrumentality of divine fidelity, justice, and care at the very core of Pauline Christianity.

As with all texts that have been reinterpreted by powerful voices, however, it is imperative to try to see this psalm without all the later lenses and layers. Peeled back, seen with one fewer filter at least, Psalm 143 can be seen as itself a powerful voice of reinterpretation, quoting and reworking passages like Psalm 28:1 (143:7: “or I will be like | those who sink in a pit”) and Lamentations 3:6 (143:3: “seated me in darkness | like the lasting dead”). It is a psalm of reawakening, life-in-death, back from the brink, whose formulas and desires are very much works in progress.