(director: on Jeduthun, an Asaph lyric)

* * *

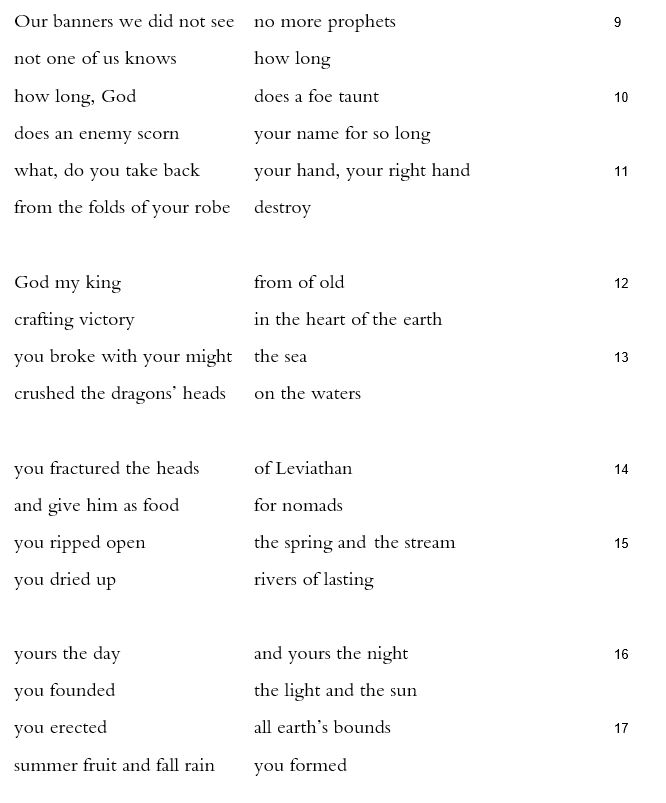

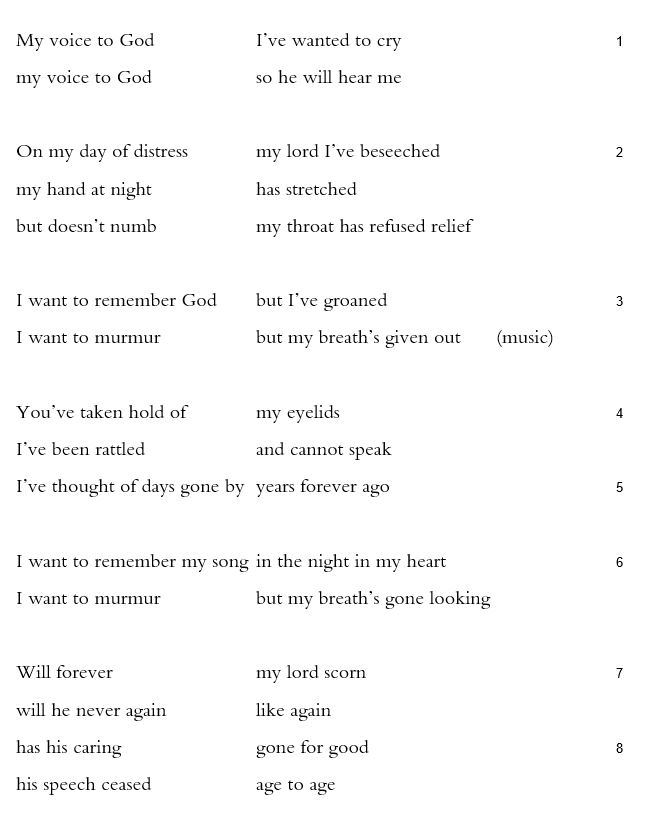

This is a sensational psalm. It is deft and layered, powerfully personal and embodied, and yet richly allusive. It transposes its first-person first half to a grand and mythic register. So much of the drama of the Asaph psalms that precede Psalm 77 is distilled here in the experience of a single speaker who wants. The cohortative mode, the “let me”/”may I” mode of wish, is crucial to the voice of the psalm. The speaker has wanted to cry out, but their body won’t let them. It won’t let them give up: “my hand at night | has stretched / but doesn’t numb | my throat has refused relief” (2); “You’ve taken hold of | my eyelids / I’ve been trembling | and cannot speak” (4).

Wants keep coming. “I want to remember,” the speaker says three times. “I want to remember God | but I’ve groaned” (3). “I want to remember my song | in the night in my heart” (6). Tellingly, right at the turn in the center of the psalm, the speaker says, “I remember | the works of Yah / oh I want to remember | your wonders gone by” (11). The desire to remember lingers even after the remembering itself. Wanting to remember keeps coming not because the speaker has forgotten, but because their desired remembering is an action, something that must be vocalized. After all, remembering in the psalm is always paired with “murmuring,” the verb used for low, meditative speech. “I want to murmur,” they say three times, twice pointing to a failure of breath: “I want to murmur | but my breath’s given out” (3); “I want to murmur | but my breath’s gone looking” (6). Murmuring, too, is at the psalm’s center:

I remember | the works of Yah

oh I want to remember | your wonders gone by

that I might mumble | all your work and your workmanship

I want to murmur God | in apartness your way

What began in verse 3 as the desire to remember God becomes in verses 12-13 the desire to murmur “God | in apartness your way.” The resolution is followed by the poem’s key question/exclamation: “Who is a god great as God | you the God who does wonders” (13-14, which are divided curiously in the Masoretic Text).

Only a few psalms earlier, it was God being asked to remember (74:2, 18, 22). Now, though God’s legendary interventions have been the subject of Psalm 74 (74:12-17), Psalm 75 (75:2-3), and nearly all of Psalm 76 (76:1-8), the speaker struggles to speak of this memory. The struggle to speak is caused by failing breath but also by God’s own silence, as verses 7-10 make clear: “has his caring | gone for good / his speech ceased | age to age” (8). The speaker’s own bodily discomfort comes from the absence of God’s body: “did he forget, God | how to feel / or shut in anger | his womb-love” (9). As always, the word for “compassion” names a part of the mother’s body, the womb, which is paired here as it is so many times, with the verb “shut.” God’s gone barren, perhaps—or the speaker just misses the womb. The speaker admits, “my sorrow is this / the sleeping right hand | of the Highest” (10). God’s sleeping hand contrasts with the speaker’s own hand, which was “stretched | but doesn’t numb” (2).

In the poem’s second half, the silence and absence of God are followed by memories. God’s arm is recalled as what ransomed “your people / the sons of Jacob | and Joseph” (15). God’s speech is recalled in deluge: “the voice of your thunder in the whirling | lightnings lit the world / the earth trembled | and it sways” (18). And, most enigmatically, hauntingly, God’s “way,” which the speaker had wanted to murmur in verse 13, is recalled as a pathway that waters erased: “by sea was your way | your winding by mighty waters / your footprints | were all unknown” (19). Did you miss God’s speech? Did you want God’s caring and womb-love, God’s tracks? These are they, the psalm says, such as they were. If it’s God’s hand you’re missing, consider this, the psalm concludes: “You led your people | like a flock / by the hand of Moses | and Aaron” (20).

The memorials of Jacob and Joseph and of Moses and Aaron are just the surface of the psalm’s allusions. The waters that erase footprints, together with the mention of clouds, the buying back of the people, all clearly gesture to the Exodus, as do close parallels between 77:13-14 and the Song of the Sea. Many scholars have cataloged these parallels and shown how they anticipate Psalms 78 and 81. But the waters and deeps of verses 16-19 allude not just to the crossing of the Reed Sea, but also the chaotic waters of creation (see also 74:12-17 and 75:3) and the story of Noah, all three of which are linked by inner-biblical reference, echo, and allusion. At the center of the story of Noah, attentive readers note, is God’s own remembering: “God remembered Noah” (Gen 8:1). Similarly, at the center of the cycle of Jacob stories, God remembers: “God remembered Rachel and God heard her and opened her womb” (Gen 30:22). This moment, too, is recalled by Psalm 77, which mentions Joseph and Jacob’s sons, and centers remembrance, and worries that a womb has shut.

Those stories of Jacob and his son Joseph are significant to this psalm as well. In verse 2, three words in a row allude to these two. The only biblical character to be “numb” (tapug) is Jacob, when he finds out Joseph is still alive (Gen 45:26). The only character to “refuse relief” (ma’anah hinacheim) is also Jacob, when he is told that Joseph has been killed (vayma’ein lehitnacheim, Gen 37:35). Later, Jacob “refuses” Joseph while reversing the blessings of Joseph’s sons, preferring Ephraim (Gen 48:19; see also Ps 78:9ff, 78:67). These allusions pinpoint key moments of father-and-son intimacy that also touch on the generativity of the family line— not just the two characters themselves but their lineage, and importantly, the lineage at the end of Genesis, which leads to the captivity in Egypt at the beginning of the book of Exodus. Even the wordplay in verses 7 and 8— both yosif, “he will (not) do again,” and he’aseif, “has it gone,” link Joseph (both roots are used multiple times in Genesis 37 and 47) and Asaph in their sound clusters— reminds readers that Joseph’s hopeful story, itself a story of remembrance, may have been followed by the terrible oppression of Pharaoh, but it was followed, almost immediately, by the hands of Moses and Aaron.