* * *

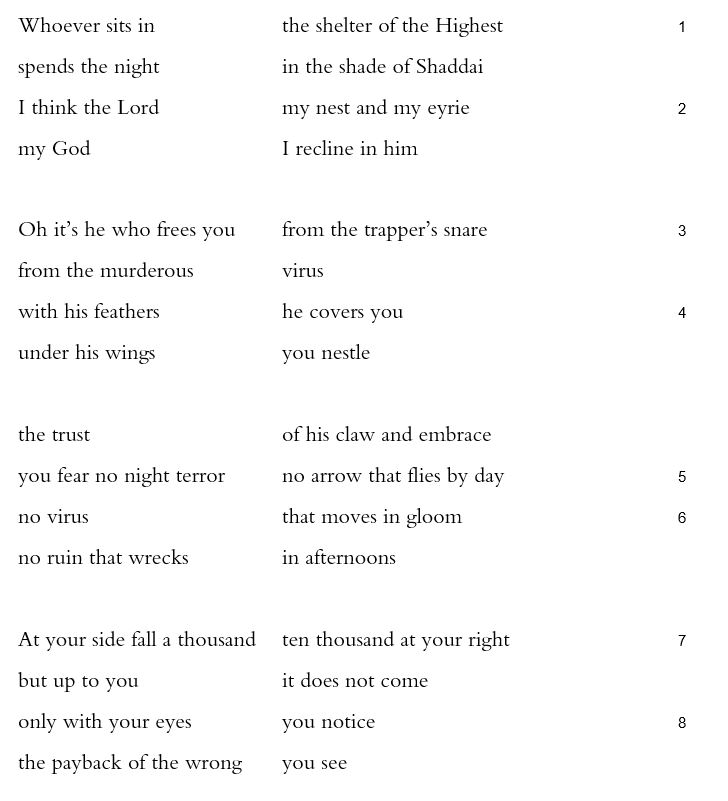

Three distinct trajectories make Psalm 91 more compelling than it first appears. The first is the unfolding of a single extended metaphor: God as a raptor, God’s devotee the raptor’s fledgling. The scene is a mountain, and the vocabulary ornithological, most explicitly in verse 4: “with his feathers | he covers you / under his wings | you nestle.” The dangers facing a juvenile bird are many, as are the threats to even those grown. But, the psalm asserts, “it’s he who frees you | from the trapper’s snare” (3), that in “the trust | of his claw and embrace”

you fear no night terror | no arrow that flies by day

no virus | that moves in gloom

no ruin that wrecks | in afternoons (4c-6).

Without the literal sense, these lines dissipate to abstraction. What does a small bird fear? Fowlers, archers, beasts of prey. Dahood reads verse “terror,” pachad, as a “pack” of wild animals, but even the words for disease and decay work on a literal level, as anyone knows who has chanced on a finch or sparrow dead from no apparent cause. Raptor imagery carries through the whole psalm, through the tenderness the Lord’s emissaries show the fledgling (“upon their palms | they lift you,” 12) to its immediate inverse, the vision of the juvenile’s future: “upon lion and cobra | you tread / you trample | serpent and young male lion” (13). The vulnerable downy fledgling that will grow wide and proud because its parents brooded and fed it, those parents’ tenderness and strength, the remoteness of their nest—all are developed through the psalm by the elaborate conceit.

At the same time, the psalm is structured by a progression of verses, beginning, middle, and end, that make the metaphor explicit in several different ways. Verse 1 has the distance of an aphorism: “Whoever sits in | the shelter of the Highest / spends the night | in the shade of Shaddai” (1). Verse 2 leaps to a first-person voice, with God in third person: “I think the Lord | my nest and my eyrie / my God | I recline in him.” The main body of the psalm, verses 3-8 and 10-13 keep God in the third person, but rely on the second person to put the reader in the young bird’s perspective: “Oh it’s he who frees you | from the trapper’s snare” (3). At the psalm’s center, we shift to direct address, God now more immediately in the second person: “Oh you Lord | my nest / the Highest | you made your home” (9). The psalm’s conclusion is even more immediately God’s perspective, in the first person, with the young bird/devotee in the third person. The more we learn of God as a mother or father bird, in other words, the closer God comes: “I want to keep him safe / I set him high | oh he knows my name” (14); “with length of days | I surfeit him / I make him see | my rescue” (16).

Easily missed is the third trajectory of the psalm, which consolidates the traits and spheres of originally separate gods under the aegis of a single Lord. The first two verses and the central verse 9 noticeably rename the Lord “my nest,” but this renaming is temporary, for the purposes of accenting God’s security and fidelity, enlivening two common terms for reliability: betach, “recline” (2), and ’emet, “trust” in “the trust | of his claw and embrace” (4). Far less temporary is the psalm’s explanation of the relationship between ’Elyon (“the Highest,” 1,9), Shaddai, YHWH (2, 9), and ’Elohei (“my God” 2). The Lord, originally from Sinai, has relocated to Zion. Worship of multiple gods, or gods of different name or avatar or location, clearly must have overlapped, given the persistence of the Bible’s centralizing tendencies. Psalm 91’s first verse is more than just an instance of synonymous parallelism between two divinities or divine appellations: “the shelter of the Highest… the shade of Shaddai.” It prepares the harder work of explaining how YHWH became synonymous with ’El ’Elyon, the Highest, which the psalm does in verse 9: “Oh you Lord | my nest / the Highest | you made your home” (9). The syntax is ambiguous, but the direction is clear: the Lord has become the Highest by nesting in the Highest’s heights.

The psalm’s second half looks different, seen this way. The Lord does not just delegate responsibilities to messengers (11). As the insistent first-person singular of the last three verses reveals, “I” am the one who does all these things. One thinks of the raptor’s claws.