(director: of the Qorachites, instructive)

* * *

By contrast with the preceding double psalm, which mentions God’s name 27 times, Psalm 44, which is longer, names Elohim only 5 times. The effect is to highlight God’s absence. In Psalm 42, it was the speaker’s enemies who asked, “where is your God?” (42:3, 10). Here, the speaker wonders much the same thing: “why are you sleeping, my lord” (23), “why are you hiding | your face” (24).

That hiddenness of God, Deus absconditus, absence, is a key theme for both of these psalms. But what Psalm 42/43 does with space, yearning for Jerusalem from afar, Psalm 44 does with time, yearning for a lost age. The speaker of the earlier psalm(s) cannot get home. What faces this speaker of this psalm is a belated era, signaled by the repeated phrase “all day long” (44:8, 15, 22) and its variants at the start of the song: “in their days | in days gone by” (44:1).

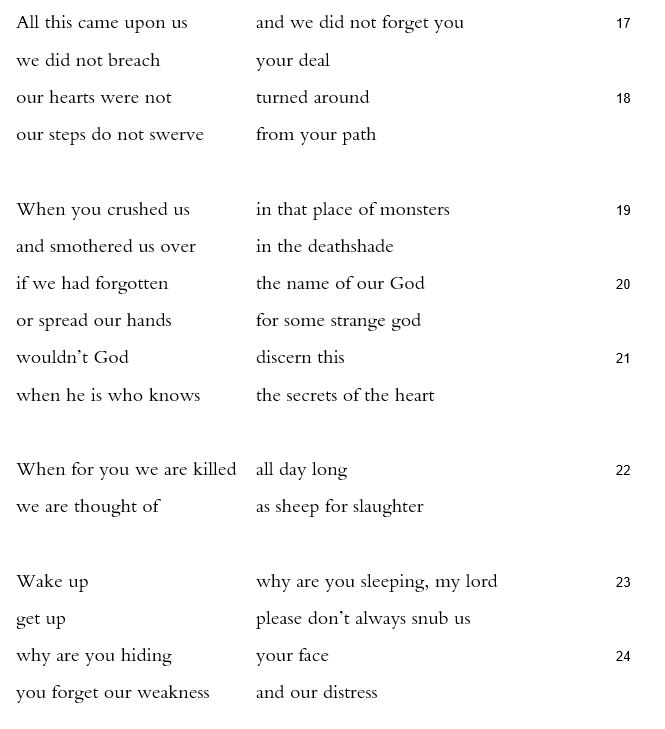

That brief refrain “all day long” reveals the psalm’s three-part shape, which mirrors the shape of the previous psalm. Here, the psalm moves from the collective memory of God’s past rescue and the logical expectation that that rescue should continue (1-8) to the brutal actuality of having been sold off to enemies (9-16) and the complaint that all of Jacob are innocent (17-26). Psalm 44 has generally been classed as a collective lament by genre critics, and indeed first-person plural “we” predicates are frequent, showing up in 1, 5, 8, 17, 20, 22. (Verses 18 and 25 each add a pair of third-person plural metonyms for “we”: “our hearts… our steps…” and “our throats… our bellies.”) Note, however, that the middle of the psalm’s three movements, verses 9-16, has none of these “we” predicates. There, the collective community shows up only as a grammatical object. Ten times as an object, in fact: twice each in verses 9 through 11, three times in 13, once in 14. In verse 12, that -einu suffix (“us”) is replaced by a third-person suffix, for the noun “your people,” which skews the psychic distance between God and God’s people slightly. “Your people” pans the camera a few degrees from “we,” a few degrees towards “you.”

Though the bulk of the poem is collective, each of its sections nears its end by shifting focus grammatically, zooming in. The psalm’s first section includes just a glimpse of an individual speaker: “it’s not my bow | I rely on / my sword | doesn’t rescue me” (6). The second section does the same: “All day long | my disgrace before me / the shame on my face | hid me” (15). These verses in the singular are spotlights. They personalize the community, with both hope for some present-era rescue and crushing disappointment. The rhetorical strategy of twice turning from the crowd to the individual creates an expectation for attentive readers and reciters. We anticipate that the third section of the psalm will end by shifting focus in much the same way. And indeed there is a shift, but not to the first-person. Instead, the psalm culminates with its only imperative verbs: “Wake up… get up” in verse 23, and “get… and buy us back” (26).

And of course it does. A shift to the first-person in a section of the psalm that insists on innocence would have undermined the whole thing. Rescue is not a function of an individual, according to this psalm. This point cannot made loudly enough or often enough, especially for those who would replace “rescue” with “salvation.” Rescue does not mean punishment for the bad. It does not mean victory or ransom or healing for the morally right. Rescue is the work God has done in the past, according to the speakers’—and speaker’s—parents. It is a function of caring, which the psalm says God has forgotten and needs to remember. Imperative reminders are its last resort.