(of Solomon)

* * *

Of all the judgments and dispositions we bring to bear as we read, maybe none matters more than disinterest. High levels of disinterestedness correspond with analytical distance and curiosity. Low levels of disinterestedness—high levels, that is, of interest and commitment—correspond with sympathy, close identification, and application to practice. Pure disinterest would be cool and clinical, pure interest hot with zeal. Approaching a text like Psalm 72, for example, a reader might wonder about it as a historical document, a cultural artifact of relevance for understanding ancient conceptions of monarchy, justice, and power. Or she might deploy the text as an ethical challenge to contemporary abuses of authority, governments that fail utterly to favor the weak, “the poor | and the oppressed” (13). Or, up through those last two amens, “let it be true | let it be true” (19), she might recite the psalm alone or with others, kneeling or clutching hands in prayer or donating money or time to those whose “blood has worth | in his eyes” (14). One and the same reader might, in one moment, patiently count syllables and speculate about stanza breaks, and in the next moment feel discomfited by the brutality of enemies licking sand, and then tear up at the picture of justice coming down like rain “and much peace | till the moon is no more” (7).

Scholarship wonders how this psalm’s model of kingship fits its historical and cultural contexts. Scholars ask compelling questions about the textual history of the psalm, when it was written, in what stages it developed by accretion, addition, revision, etc. How does the superscription relate to the postscript, that this poem is Solomon’s and David’s at once? Why end the second collection of psalms with this— besides its obvious emotional power and comprehensive vision of a just society? Jewish and Christian practice tend to show interest in the messianic implications, kneeling to a divinely inspired autarch whose hands will provide fertility and fairness. And liturgy tends to excerpt just lines 17-19, the least concrete and therefore most extractible lines, as part of more general praise and worship.

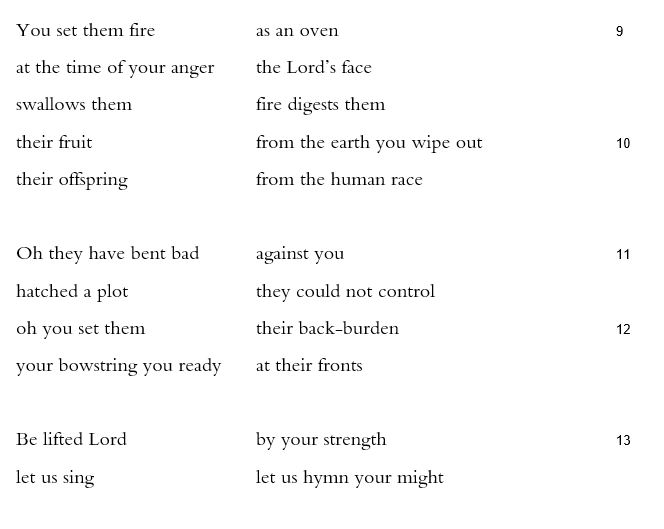

A crucial feature of this psalm, impossible to achieve in translation, is that so many of its verbs are temporally undecidable. In the so-called yiqtol form, Hebrew verbs can be rendered by any number of tenses and aspects and moods, from present tense to past imperfect, to future indicative, to present cohortative and jussive. Verses 2 and 3, for instance, are here expressed in this way:

May he rule your people | justly

your weak ones | judiciously

that the hills might bear | the people peace

and the hillocks | justice

But “may he rule” could also be “He rules” or “He will rule” or even “that he may rule” (that is, “let him rule”). And “that the hills might bear” could also be— indeed, in Hebrew, it also IS— “the hills will bear” and “the hills bear” and “let the hills bear.” There is an argument to be made for making as few inferences as possible, presenting every prefixed verb form here in the simple present tense, as the tense that conveys the greatest semantic range, that least forces the issue. Using future tenses captures the poem’s most eschatological resonance, but only by deferring justice and abundance, the rescue of the imprisoned, that single fistful of grain that fruits and waves and feeds cities, putting off fulfillment until a time more distant than the mentions of Tarshish and Sheba suggest. The present tense captures immediacy, but by presenting the vision as already accomplished, which may overly automate the process. The modality of “may” and “might,” the wish is the thing with most of these verbs.

Disinterestedness must become less disinterested when there are military generals in 21st-century America barking that the nation ought to have one single religion, or when officials ground their grift by wrapping nationalism in theories of the divine right of kings. Does Psalm 72 support such dangerous claims? Or does it weigh against them? Prooftext-seekers snip verses like “may he control | sea to sea / from the river | to the limits of earth” (8) or repost all the lines about kneeling and tribute. But the wish is what guides this psalm. The king’s justice is not the king’s. Justice is greater-than. Justice requires special attention to “the oppressed | who cries out / the weak | who has no one to help” (12). Even time and space depend upon justice, according to the psalm: the hills, hillocks, the hilltops, “the face of the moon” (5), “the face of the sun” (17).